stdClass Object

(

[id] => 16346

[title] => Anorexia of Compassion. A New Concern for Feelings

[alias] => anorexia-of-compassion-a-new-concern-for-feelings

[introtext] => Commentaries – Facing all the pain pervading our days

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 29/07/2016

Our capacity to suffer because of the suffering of others and to rejoice for their joy has gone through a very rapid decline in a few decades. The consumer and comfort-focused society confuses well-being with the reduction of all forms of suffering, forgetting one of the most profound and ancient truths: that there are many good pains in human life, as there are many evil pleasures, too.

[fulltext] =>

And so television, this new postmodern totem, promises us a happier life, making us move on from the latest massacre in France to the latest game show in a matter of seconds, resulting in a flattening out of the events which generates a downward levelling of our emotions and feelings.

The great achievements of democracy, rights and freedoms are the mature fruit of millennia of civilization and faith, where we learned to suffer and become indignant for new and different things: for the denied freedom of others, for their crushed rights, for the injustices towards people who were not our relatives or friends. Without these new pains we would not have been able to come out of regimes, we would not have broken free from the pharaohs or the many forms of slavery and servitude.

This type of social emotions is partly natural, but its intensity and quality are the result of culture and the education of character. Of course we feel a sense of discomfort when we come in contact with those suffering around us, but to feel it so strong as to move us to action, to rush to their aid something more than natural is needed. Experiencing discomfort because of a victim that we meet along the way is natural; taking care of them is called culture.

Empathy is natural; compassion isn't because it comes from the cultivation, on an individual  and collective level, of some special emotions and higher feelings. Social norms, as Adam Smith reminded us already in the mid eighteenth century, are generated by the capacity that human beings have developed to approve and blame the actions and feelings of others (and their own), using the faculty he calls 'sympathy'. Social balance is the result of the spontaneous order of the dynamic of feelings, just as the market is the result of the dynamics of interest.

and collective level, of some special emotions and higher feelings. Social norms, as Adam Smith reminded us already in the mid eighteenth century, are generated by the capacity that human beings have developed to approve and blame the actions and feelings of others (and their own), using the faculty he calls 'sympathy'. Social balance is the result of the spontaneous order of the dynamic of feelings, just as the market is the result of the dynamics of interest.

This balance of feelings, however, can get stabilized either at low levels (for example, in a bandits' society) or at a high levels, when people develop religions, art, philosophy, beauty and pietas. But also the 'high' moral order of feelings, like all things fragile (because delicate), can be shattered overnight due to a lack of care and care giving. And as with almost all abilities and virtues, if compassion and indignation are not cultivated and practised they get wasted and regress to lower moral levels.

Constant exposure to the economic ideology and that of consumption turns us into animals less and less able to sympathize and become indignant: only twenty years ago we were much better at it. We are facing a world where we will be increasingly capable of natural and easy emotions towards kittens and puppies, but we will not be able to show solidarity and feel pain over the poverty and injustice around us. Globalization did not empower these feelings, but crushed them and reduced their intensity and effectiveness, making us more capable of simple, ‘low-cost’ emotions but less capable of complex and ‘expensive’ ones. In the western part of the world this latter type emotions were the result of a complex process, where biblical Christianity and humanism have played a key role.

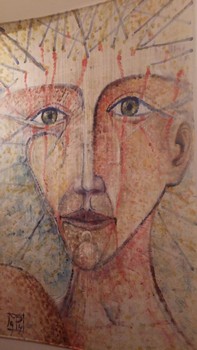

Looking at the statues and stories of martyrs and saints we have learned to feel differently in our soul as we observe and meditate about the paintings and frescoes of the Nativity, the parables, the crosses and the resurrections in the churches. During mass, our grandparents did not understand all the words, but they understood the gospel of the images very well - we can see this even today, when children come to church, and are much more capable than us to enter into a dialogue with the paintings and the faces around them.

If we want to seriously respond to this crisis in our ability to feel and suffer about great and high things, we have to work harder and differently with our young and our children today, recognizing a special role of the school, which is one of the few global public goods that still remained. Literature, art and music are essential to form the emotions and the deepest and greatest kind of feelings in all but especially in children and young adults. The first fairy tales, a famous poem, the stories of Don Rodrigo, the prodigal son or St. Martin have all given us as a free gift the letters with which we wrote down the first few sentences of our consciousness and indignation, the ones with which we have learned to cry for the sorrows and joys of others, to suffer and rejoice for people we have never met and who never existed (but are more real and true than many of our neighbours). If we do not encounter at least one poet who loves the naked truth (Giacomo Leopardi, for example) while we are still young, as adults we won't be able to free ourselves from ideologies, and will surrender to some idol offering simple answers to our even simpler questions.

Today our children grow up being educated mainly by the television and mobile phones, in the company of new soap operas for kids, which do not represent anything more on the screen than what the boys live every day, without any ability to make them dream and wish for greater things than what’s already in their heart. The television stories of my childhood were 'Pinocchio' by Collodi, played by Comencini and 'Michael Strogoff' by Decourt, adapted from Jules Verne. Not long ago I listened to the soundtracks of those films again and suddenly I had a flashback of those days and my first emotions about good and evil by others - I learned it without a teacher’s help that a father can sell his only jacket to be able to send his son to school and that a poor farmer may donate his only horse for a greater ideal.

Today our children grow up being educated mainly by the television and mobile phones, in the company of new soap operas for kids, which do not represent anything more on the screen than what the boys live every day, without any ability to make them dream and wish for greater things than what’s already in their heart. The television stories of my childhood were 'Pinocchio' by Collodi, played by Comencini and 'Michael Strogoff' by Decourt, adapted from Jules Verne. Not long ago I listened to the soundtracks of those films again and suddenly I had a flashback of those days and my first emotions about good and evil by others - I learned it without a teacher’s help that a father can sell his only jacket to be able to send his son to school and that a poor farmer may donate his only horse for a greater ideal.

There is little hope for a change of course in television, whether public or private, as it is increasingly in the hands of profit oriented sponsors. What about school, though? Western governments are reducing the space of art education and humanities, in all types of schools and in all grades. In a culture where faiths and the great collective narratives have lost their space, if young people are also systematically deprived of literature, art, loud music and poetry, it will only produce people without those passions and feelings that are the more important for living together in peace and freedom. If we do not react to this anorexia of compassion, our children will quickly pass through the city centre of Warsaw but will not 'revisit' the ghetto with its 450 thousand Jews who were deported and killed there, they will not get into that synagogue and cry there for shame. And that would be an awfully sad day. The capacity for compassion for one's people is an immense resource of the peoples. It is no less valuable than oil or technology. Starting to talk about its deterioration is the first step to try to reconstitute this heritage that's in ruins now.

Download article in pdf

[checked_out] => 0

[checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[catid] => 888

[created] => 2016-07-29 08:14:17

[created_by] => 64

[created_by_alias] =>

[state] => 1

[modified] => 2023-04-14 14:31:53

[modified_by] => 64

[modified_by_name] => Antonella Ferrucci

[publish_up] => 2016-09-01 08:14:00

[publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[images] => {"image_intro":"","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""}

[urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""}

[attribs] => {"article_layout":"","show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_associations":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_page_title":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":"","helix_ultimate_image":"","helix_ultimate_image_alt_txt":"","spfeatured_image":"","helix_ultimate_article_format":"standard","helix_ultimate_audio":"","helix_ultimate_gallery":"","helix_ultimate_video":"","video":""}

[metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""}

[metakey] =>

[metadesc] =>

[access] => 1

[hits] => 4027

[xreference] =>

[featured] => 0

[language] => en-GB

[on_img_default] => 1

[readmore] => 7749

[ordering] => 30

[category_title] => EN - Avvenire Editorials

[category_route] => economia-civile/it-editoriali-vari/it-varie-editoriali-avvenire

[category_access] => 1

[category_alias] => en-avvenire-editorial

[published] => 1

[parents_published] => 1

[lft] => 79

[author] => Antonella Ferrucci

[author_email] => ferrucci.anto@gmail.com

[parent_title] => IT - Editoriali vari

[parent_id] => 893

[parent_route] => economia-civile/it-editoriali-vari

[parent_alias] => it-editoriali-vari

[rating] => 0

[rating_count] => 0

[alternative_readmore] =>

[layout] =>

[params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object

(

[data:protected] => stdClass Object

(

[article_layout] => _:default

[show_title] => 1

[link_titles] => 1

[show_intro] => 1

[info_block_position] => 0

[info_block_show_title] => 1

[show_category] => 1

[link_category] => 1

[show_parent_category] => 1

[link_parent_category] => 1

[show_associations] => 0

[flags] => 1

[show_author] => 0

[link_author] => 0

[show_create_date] => 1

[show_modify_date] => 0

[show_publish_date] => 1

[show_item_navigation] => 1

[show_vote] => 0

[show_readmore] => 0

[show_readmore_title] => 0

[readmore_limit] => 100

[show_tags] => 1

[show_icons] => 1

[show_print_icon] => 1

[show_email_icon] => 1

[show_hits] => 0

[record_hits] => 1

[show_noauth] => 0

[urls_position] => 1

[captcha] =>

[show_publishing_options] => 1

[show_article_options] => 1

[save_history] => 1

[history_limit] => 10

[show_urls_images_frontend] => 0

[show_urls_images_backend] => 1

[targeta] => 0

[targetb] => 0

[targetc] => 0

[float_intro] => left

[float_fulltext] => left

[category_layout] => _:blog

[show_category_heading_title_text] => 0

[show_category_title] => 0

[show_description] => 0

[show_description_image] => 0

[maxLevel] => 0

[show_empty_categories] => 0

[show_no_articles] => 1

[show_subcat_desc] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles] => 0

[show_cat_tags] => 1

[show_base_description] => 1

[maxLevelcat] => -1

[show_empty_categories_cat] => 0

[show_subcat_desc_cat] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 0

[num_leading_articles] => 0

[num_intro_articles] => 14

[num_columns] => 2

[num_links] => 0

[multi_column_order] => 1

[show_subcategory_content] => -1

[show_pagination_limit] => 1

[filter_field] => hide

[show_headings] => 1

[list_show_date] => 0

[date_format] =>

[list_show_hits] => 1

[list_show_author] => 1

[list_show_votes] => 0

[list_show_ratings] => 0

[orderby_pri] => none

[orderby_sec] => rdate

[order_date] => published

[show_pagination] => 2

[show_pagination_results] => 1

[show_featured] => show

[show_feed_link] => 1

[feed_summary] => 0

[feed_show_readmore] => 0

[sef_advanced] => 1

[sef_ids] => 1

[custom_fields_enable] => 1

[show_page_heading] => 0

[layout_type] => blog

[menu_text] => 1

[menu_show] => 1

[secure] => 0

[helixultimatemenulayout] => {"width":600,"menualign":"right","megamenu":0,"showtitle":1,"faicon":"","customclass":"","dropdown":"right","badge":"","badge_position":"","badge_bg_color":"","badge_text_color":"","layout":[]}

[helixultimate_enable_page_title] => 1

[helixultimate_page_title_alt] => Avvenire Editorials

[helixultimate_page_subtitle] => Civil Economy

[helixultimate_page_title_heading] => h2

[page_title] => Avvenire Editorials

[page_description] =>

[page_rights] =>

[robots] =>

[access-view] => 1

)

[initialized:protected] => 1

[separator] => .

)

[displayDate] => 2016-07-29 08:14:17

[tags] => Joomla\CMS\Helper\TagsHelper Object

(

[tagsChanged:protected] =>

[replaceTags:protected] =>

[typeAlias] =>

[itemTags] => Array

(

)

)

[slug] => 16346:anorexia-of-compassion-a-new-concern-for-feelings

[parent_slug] => 893:it-editoriali-vari

[catslug] => 888:en-avvenire-editorial

[event] => stdClass Object

(

[afterDisplayTitle] =>

[beforeDisplayContent] =>

[afterDisplayContent] =>

)

[text] => Commentaries – Facing all the pain pervading our days

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 29/07/2016

Our capacity to suffer because of the suffering of others and to rejoice for their joy has gone through a very rapid decline in a few decades. The consumer and comfort-focused society confuses well-being with the reduction of all forms of suffering, forgetting one of the most profound and ancient truths: that there are many good pains in human life, as there are many evil pleasures, too.

[jcfields] => Array

(

)

[type] => intro

[oddeven] => item-odd

)

A great utopia of our capitalism is the construction of a society where there is no more need for human labour. There has always been a spirit of the economy that dreamed of "perfect" enterprises and markets to the point where you can manage without humans beings. Managing and controlling men and women is much more difficult than managing docile machines and obedient algorithms. Real people go through crises, they protest, they enter into conflict with each other, they always do things other than those that they should do according to their job descriptions, often they do better things.

A great utopia of our capitalism is the construction of a society where there is no more need for human labour. There has always been a spirit of the economy that dreamed of "perfect" enterprises and markets to the point where you can manage without humans beings. Managing and controlling men and women is much more difficult than managing docile machines and obedient algorithms. Real people go through crises, they protest, they enter into conflict with each other, they always do things other than those that they should do according to their job descriptions, often they do better things. Resurrection is a great word on earth. Life reborn from death is the first law of nature, that of plants and flowers that fill the world with colour and beauty, because they tell us that life is greater than death that feeds it. Women and men are reborn many times throughout their existence, finding themselves resurrected after grief, abandonment, depression or diseases that had crucified them before. Sometimes we rise again by resurrecting someone else from their tomb, and those have surely been the most beautiful and true resurrections we have witnessed. If resurrection had not been a human word, a friend and something familiar, those women and men of Galilee would not have been able to perceive anything of the unique mystery that had been completed between the cross and the day after the Sabbath.

Resurrection is a great word on earth. Life reborn from death is the first law of nature, that of plants and flowers that fill the world with colour and beauty, because they tell us that life is greater than death that feeds it. Women and men are reborn many times throughout their existence, finding themselves resurrected after grief, abandonment, depression or diseases that had crucified them before. Sometimes we rise again by resurrecting someone else from their tomb, and those have surely been the most beautiful and true resurrections we have witnessed. If resurrection had not been a human word, a friend and something familiar, those women and men of Galilee would not have been able to perceive anything of the unique mystery that had been completed between the cross and the day after the Sabbath.

The duty of hospitality is the main wall of western civilization, and the ABC of good of humanity. In the ancient Greek world a stranger was the bearer of a divine presence. There are many myths in which the gods take the form of passing strangers. The Odyssey is also a great lesson on the value of hospitality (Nausicaa, Circe...) and the severity of its desecration (Polyphemus the Cyclops, Antinous). In ancient times, hospitality was regulated by real sacred rites, as an expression of the reciprocity of gifts. From the first gesture of welcome to the moment of the guest's departure, complete with a "parting gift" the host had several duties which he had to perform in a discrete and above all, grateful way.

The duty of hospitality is the main wall of western civilization, and the ABC of good of humanity. In the ancient Greek world a stranger was the bearer of a divine presence. There are many myths in which the gods take the form of passing strangers. The Odyssey is also a great lesson on the value of hospitality (Nausicaa, Circe...) and the severity of its desecration (Polyphemus the Cyclops, Antinous). In ancient times, hospitality was regulated by real sacred rites, as an expression of the reciprocity of gifts. From the first gesture of welcome to the moment of the guest's departure, complete with a "parting gift" the host had several duties which he had to perform in a discrete and above all, grateful way. The topic of welfare, well-being, public happiness or social well-being has been and still is at the centre of the Italian tradition of civil economy. In recent years there was a significant growth of the debate around the need to go beyond GDP or, according to some, to start using other indicators telling about the other dimensions of well-being as well.

The topic of welfare, well-being, public happiness or social well-being has been and still is at the centre of the Italian tradition of civil economy. In recent years there was a significant growth of the debate around the need to go beyond GDP or, according to some, to start using other indicators telling about the other dimensions of well-being as well. The European Community, like every community, is a form of common good. And as the economic science teaches us, common goods are by their nature subject to the possibility of their own destruction. The so-called 'tragedy of the commons' (Garrett Hardin, 1968) is a well-known term for a what happens when the users of a common resource seek to maximize their individual interests, forgetting or leaving too much in the background the deterioration of the common resource caused by their consumption. If - as in the most famous example - the users of the same piece of grazing land only look at their own costs and benefits, they feel induced to bring more and more cows out, and so the final outcome of the process will be the destruction of the pasture.

The European Community, like every community, is a form of common good. And as the economic science teaches us, common goods are by their nature subject to the possibility of their own destruction. The so-called 'tragedy of the commons' (Garrett Hardin, 1968) is a well-known term for a what happens when the users of a common resource seek to maximize their individual interests, forgetting or leaving too much in the background the deterioration of the common resource caused by their consumption. If - as in the most famous example - the users of the same piece of grazing land only look at their own costs and benefits, they feel induced to bring more and more cows out, and so the final outcome of the process will be the destruction of the pasture. So many people talk about economic recovery and GDP nowadays, as if GDP alone was capable of telling good tidings to us. The reality of our economy, however, says that businesses are suffering and will continue to suffer for a long time, and so will the world of work, too. And it is not only for the lack of markets and sales that they suffer. In fact, a common cause of suffering and failure can be found in some typical errors in the management of workers during the crisis. When going through long and difficult phases, in fact, we are more likely to commit many serious mistakes in the relationships between the ruling class and workers.

[fulltext] =>

So many people talk about economic recovery and GDP nowadays, as if GDP alone was capable of telling good tidings to us. The reality of our economy, however, says that businesses are suffering and will continue to suffer for a long time, and so will the world of work, too. And it is not only for the lack of markets and sales that they suffer. In fact, a common cause of suffering and failure can be found in some typical errors in the management of workers during the crisis. When going through long and difficult phases, in fact, we are more likely to commit many serious mistakes in the relationships between the ruling class and workers.

[fulltext] =>  Canadian political scientist Jennifer Nedelsky, professor at the University of Toronto, is one of the most innovative voices in the debate on the issues of care, rights and social relations. She is convinced that in our time there is a big priority that, however and unfortunately, remains much in the background of the life of democracies: the profound rethinking of the relationship between work and care, and thus between men and women, the young and the old, the rich and the poor. In fact, it is a critical issue in a world with more and more elderly people, and with elderly people who, thank God, live longer and longer. Without a collective and serious breakthrough in the culture of care in relation to the culture of work, democracy and equality among people are basically denied. I've known professor Nedelsky for a few years (and that explains the informal register of our interview); this time I met her in Italy at the

Canadian political scientist Jennifer Nedelsky, professor at the University of Toronto, is one of the most innovative voices in the debate on the issues of care, rights and social relations. She is convinced that in our time there is a big priority that, however and unfortunately, remains much in the background of the life of democracies: the profound rethinking of the relationship between work and care, and thus between men and women, the young and the old, the rich and the poor. In fact, it is a critical issue in a world with more and more elderly people, and with elderly people who, thank God, live longer and longer. Without a collective and serious breakthrough in the culture of care in relation to the culture of work, democracy and equality among people are basically denied. I've known professor Nedelsky for a few years (and that explains the informal register of our interview); this time I met her in Italy at the  “Parallel with the intensification of the economic crisis, a greater spread of the phenomenon of usury was observed, evidenced by reports of the doubling of suspicious transactions in 2013 over the previous year.” There are documents like this one – just published by the Financial Information Unit of the Bank of Italy – that every responsible and mature citizen should read, meditate on, and then act accordingly. Usury is a typical disease of any monetary society, since it is the visible phenomenon of the power relations and the power that are hidden under the apparent neutrality of money. The existence of money has many benefits, but it also generates high costs that are growing in intensity and importance with the expansion of the area covered by money within society.

“Parallel with the intensification of the economic crisis, a greater spread of the phenomenon of usury was observed, evidenced by reports of the doubling of suspicious transactions in 2013 over the previous year.” There are documents like this one – just published by the Financial Information Unit of the Bank of Italy – that every responsible and mature citizen should read, meditate on, and then act accordingly. Usury is a typical disease of any monetary society, since it is the visible phenomenon of the power relations and the power that are hidden under the apparent neutrality of money. The existence of money has many benefits, but it also generates high costs that are growing in intensity and importance with the expansion of the area covered by money within society. We always knew that the Gross Domestic Product does not measure much and that many of the things that it measures it measures badly - and we often and willingly say this on these pages. But no one has ever thought of eliminating GDP to let other indicators of well-being take its place, because although democracy has a growing need for more economic and social indicators, it is still important to have an indicator of the production of goods and services of a country. The GDP is full of data that say little about our well-being or express exactly the opposite (e.g. gambling).

We always knew that the Gross Domestic Product does not measure much and that many of the things that it measures it measures badly - and we often and willingly say this on these pages. But no one has ever thought of eliminating GDP to let other indicators of well-being take its place, because although democracy has a growing need for more economic and social indicators, it is still important to have an indicator of the production of goods and services of a country. The GDP is full of data that say little about our well-being or express exactly the opposite (e.g. gambling). If we want to continue to write work as the first word of our social contract, today we have put some other words before it. Among these there is the care that goes along with work. To re-invent work the first thing to do is to recognize that a person's work experience must go beyond paid work (job) to include activities of care provided in the family and in the community. In the twentieth century we confined work to the workplace, to the factory and the office, leaving off all that work that had not been counted or valued only because it took place outside of the "labour market".

If we want to continue to write work as the first word of our social contract, today we have put some other words before it. Among these there is the care that goes along with work. To re-invent work the first thing to do is to recognize that a person's work experience must go beyond paid work (job) to include activities of care provided in the family and in the community. In the twentieth century we confined work to the workplace, to the factory and the office, leaving off all that work that had not been counted or valued only because it took place outside of the "labour market".