stdClass Object

(

[id] => 19636

[title] => Capitalism, a new Catholic spirit

[alias] => capitalism-a-new-catholic-spirit

[introtext] => The land of We/8 - The market, the merchants and the Gospel: scientific reflection and social works

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 11//11/2023

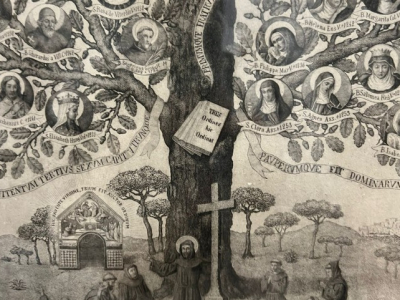

The era of the medieval merchants and of their companies where in the Book of Reason, the main account was listed under the name of "Messer Domineddio", was the time when the alliance between the merchants and the mendicant friars generated Florence, Padua or Bologna. It was an extraordinary era that failed to become the modern Italian and Meridian economic culture because the Lutheran Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation split Europe in two and prevented the medieval civil seeds from fully flourishing. It was, paradoxically, the Protestant Nordic world that gained a part of the legacy of the first medieval market economy (but without its charisms, without Francis and Benedict), although it was born in controversy with the wealth of the Roman Christianity of the Renaissance Popes. Catholic countries, including Italy in a special way, experienced the Protestant Reformation as a religious and civil trauma, and the results were typical of a major collective trauma. We cannot know what Italian and Meridian society and economy could have become if that alliance between Franciscans and merchants had continued after the sixteenth century, if the Catholic Church had not been afraid, at times terrified, in the face of any form of individual freedom, convinced that the "internal forum" without the control of the pastors was too exposed to the winds of heresy coming from the North. All that class of humanist merchants that developed between Dante and Masaccio, Michelangelo and Machiavelli, the businesses and banks of the Tuscans and the Lombards, shattered on the rock of the Council of Trent. With the end of the sixteenth century the Baroque age began which contributed some artistic and literary excellence but did not generate children and grandchildren equal to those first merchants who were friends of the friars and the cities. The Baroque history of Italy is the story of an interrupted path, of an unfinished civil, religious and economic history which had determining effects on the shape of the modern economy and society under the Alps. That set of theology, legal and moral norms, practices and prohibitions, fears and anxieties that we call Counter-Reformation (I do not use the expression of Catholic Reformation, even if there was a Reformation in the Catholic Counter-Reformation and a Counter-Reformation in the Protestant Reformation) has not only conditioned our religious life, it has also changed and shaped our businesses, politics, banks, communities, families and taxes.

[fulltext] =>

In this Italy of the Counter-Reformation, despite everything, some dimensions of the medieval and Renaissance economic ethos nevertheless managed, to survive the restoration. Some ancient spirit slipped into the hidden places between the folds of people's lives, into the living spaces not occupied by religious power. These were often submerged spaces, real karst rivers, where some merchants and bankers managed to wedge themselves without being discouraged and defeated by the manuals for confessors or by the anti-economic and anti-civil catechisms of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In these centuries, many Monti di Pietà died out but others became commercial banks. We have seen that the Grain Banks survived longer, for four centuries, and were poor but decisive resources for Southern Italy. There were few but there were some scholars of economics, who, navigating between prohibitions and ecclesiastical condemnations, wrote beautiful pages of economic theory. First Antonio Serra and Tommaso Campanella, then Ludovico Muratori and Scipione Maffei were that ideal bridge that united the shores of civil Humanism with the reforming Enlightenment of Genovesi and his Neapolitan civil school (of Dragonetti, Longano, Odazi, Filangieri, Galanti...), which was one of the brightest seasons in Italian history. The economic eighteenth century soon clashed with the restoration of the first decades of the nineteenth century, and then anti-modernism between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the years of the Non-expedit of Pius IX and the Pascendi dominici gregis of Pius X (1907), which was culturally similar to the climate created by the Counter-Reformation in past centuries.

Coming directly to economics, in the 1820s and 1830s, the Neapolitan Francesco Fuoco wrote texts that were still entirely Genoese, and therefore humanist, pages inherited from the humanist merchant-bankers of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in Tuscany. But with Fuoco, the Genoese tradition of Civil Economy ended, because with the mid-nineteenth century our best economists re-founded the Italian tradition on French and English bases, without any vital link with the Neapolitan and Italian eighteenth century. We still had good economists but now they were all very distant from the Genoese and inserted into the main flow of a new, international and increasingly Anglo-Saxon-led science. Italy became a periphery, although it was still respected until the Second World War (thanks above all to the widely held enormous esteem for Vilfredo Pareto).

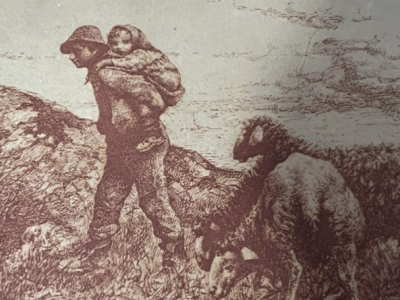

However, between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, not many Italian economists, even very talented ones, attempted to reconnect with the classic Italian tradition, without following the single bandwagon of science in its new tracks. One of these, and perhaps the most interesting one, is Achille Loria (1857-1943), from Mantua, whom we left last week with his "theory of rent", similar to that of Francesco Fuoco. Loria was among the few economists of his time who did not forget about the Grain Banks: "The Grain Banks, which lent wheat in kind, giving the borrower, at the time of sowing, a waning bushel of wheat and receiving, at the time of harvest, a full bushel of wheat: the difference between the two bushels represented the interest. But over time this loan was mostly made in favour of the large owners and therefore it lost all its philanthropic character, which constituted its merit" (Course in Political Economy, 1927, p.695). Loria's interest in rent, which he placed at the centre of his system, was an expression of a vision of the economy and society centred on profits and therefore on entrepreneurs, on the productive class, therefore critical of the parasitic tendency of Italian culture, which grew exponentially during the Counter-Reformation. The seventeenth century was in fact a time of return to the land, of the nobility of blood, of counts and marquises, of a class of nobles who lived without working and all the rest of society who worked without living: "Then comes another distinction of social classes, shaped by the distinction of capital into productive and unproductive: that of the productive capitalists, exclusively devoted to industry and that of the unproductive who do not increase social wealth but speculate on values, forming their income by extracting from the income of others" (The economic synthesis, 1910, p. 211).

However, one question remains. Loria was a follower of the Italian civil tradition, but he was not Catholic (he was from a Jewish family): where then was Catholic economic thought in the twentieth century directed? Loria also wrote about cooperation and the cooperative movement. It was in the writings on cooperation, on rural savings banks, and then on savings banks that we find some of the most beautiful pages of Civil Economy by Italian writers, starting from the second half of the nineteenth century, including some beautiful ones by Giuseppe Mazzini. Just as in the time of the Counter-Reformation, Italian Catholics dedicated themselves to the establishment of the Monti di Pietà, the Grain Banks and to an enormous quantity (and quality) of social works, schools, hospitals, also the night of free thinking between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries anti-modernists saw a great proliferation of social works, institutions, cooperatives, banks and non-academic writers who were skilled builders of the common good.

However, this does not mean that the anti-modernist wave of the Catholic Church did not also heavily involve the few Catholic economists of the first half of the twentieth century, from Giuseppe Toniolo up to Amintore Fanfani. This Catholic tradition, which had an important centre in the early days of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart of Milan founded by Agostino Gemelli, continued to view the Middle Ages as the golden age and the Scholasticism of Thomas as the highest point of Christian culture and philosophy, also in the economic field. For Fanfani, an author with his own brilliance and originality, the ethical pinnacle of economic ethics was reached between the thirteenth and the early fourteenth centuries, when, with the first hints of Humanism – interpreted as a resurgence of paganism – the decline of Christian civilization began. This gave rise, as early as the end of the fourteenth century, to the spirit of capitalism, which for Fanfani was an evil spirit. Fanfani, criticizing (perhaps without understanding) Max Weber, affirmed that capitalism did not originate in the Protestant world but in Italy between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, when economic practices abandoned the teachings of Scholasticism and began to follow different paths far from authentic evangelical humanism: "Throughout the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the number of those who adopted illicit methods in the acquisition of wealth, according to Thomistic rules, increased ... The neighbour lost the physiognomy of brother and acquired that of competitor, that is, of enemy" (The origins of the capitalist spirit in Italy, Vita e Pensiero, 1933, p.162). Thus, merchants such as Marco Francesco Datini redeemed themselves from a misguided life "trying to make amends at the point of death" (p.165). Because, by then, "wealth is a means solely for satisfying one's needs" (p.165). Instead, until the mid-fourteenth century, for Fanfani the economy was Christian because "economic activity, like all other human activities, had to revolve around God... Everyone met in one idea: that of Theo-centricity" (p.158). The fifteenth century was therefore the birth of the spirit of the capitalist who "knows no other limit of conduct than that of utility" (p.155).

Thus, all the work of the Franciscan school between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (which Fanfani and Toniolo ignored or did not take seriously), which had led to a new conception of civil profit and the merchant as a friend of the city, was considered degeneration and decadence by the true Christian spirit, the one which was dominated by Thomism, where people worked only for the common good, because, it was believed that working for private gain is only a form of selfishness and the pursuit of personal utility. So his vision that pits Humanism against Scholasticism, and above all considers the centrality of God in competition with the centrality of man, as if God wanted a world entirely directed to himself, a Father who would not enjoy the autonomy of his children by wanting them all for his exclusive service – what non-incestuous father would ever do that? Thus it was forgotten that the fourteenth, fifteenth and sixteenth centuries were the centuries when the alliance between Franciscans and merchants had worked authentic economic, civil, artistic and spiritual miracles and the enmity between the centrality of God and the centrality of men that had dominated the Counter-Reformation returned in the twentieth century.

Many documents of the Social Doctrine of the Church reflect these anti-modern, anti-market, anti-entrepreneur and anti-bank decades (it is not surprising that neither the word entrepreneur nor bank is present in our Constitution). This is why today it would be not only urgent but very necessary for the studies of Social Doctrine to truly start again from Humanism, from that period when the market was born from the Christian spirit, from merchants and beggars together, from the Gospel, not against it. This is what we have tried to do in these last few weeks. Thank you to those who have followed us on this challenging but perhaps somewhat useful journey.

[checked_out] => 0

[checked_out_time] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[catid] => 1168

[created] => 2023-11-12 08:21:58

[created_by] => 64

[created_by_alias] => Luigino Bruni

[state] => 1

[modified] => 2023-11-29 10:30:41

[modified_by] => 64

[modified_by_name] => Antonella Ferrucci

[publish_up] => 2023-11-12 08:21:28

[publish_down] => 0000-00-00 00:00:00

[images] => {"image_intro":"","float_intro":"","image_intro_alt":"","image_intro_caption":"","image_fulltext":"","float_fulltext":"","image_fulltext_alt":"","image_fulltext_caption":""}

[urls] => {"urla":false,"urlatext":"","targeta":"","urlb":false,"urlbtext":"","targetb":"","urlc":false,"urlctext":"","targetc":""}

[attribs] => {"article_layout":"","show_title":"","link_titles":"","show_tags":"","show_intro":"","info_block_position":"","info_block_show_title":"","show_category":"","link_category":"","show_parent_category":"","link_parent_category":"","show_associations":"","show_author":"","link_author":"","show_create_date":"","show_modify_date":"","show_publish_date":"","show_item_navigation":"","show_icons":"","show_print_icon":"","show_email_icon":"","show_vote":"","show_hits":"","show_noauth":"","urls_position":"","alternative_readmore":"","article_page_title":"","show_publishing_options":"","show_article_options":"","show_urls_images_backend":"","show_urls_images_frontend":"","helix_ultimate_image":"images\/2023\/11\/11\/231111_La_terra_del_noi_08_ant.jpg","helix_ultimate_image_alt_txt":"","spfeatured_image":"images\/2023\/11\/11\/231111_La_terra_del_noi_08_ant.jpg","helix_ultimate_article_format":"standard","helix_ultimate_audio":"","helix_ultimate_gallery":"","helix_ultimate_video":"","video":""}

[metadata] => {"robots":"","author":"","rights":"","xreference":""}

[metakey] =>

[metadesc] =>

[access] => 1

[hits] => 2296

[xreference] =>

[featured] => 1

[language] => en-GB

[on_img_default] => 0

[readmore] => 9734

[ordering] => 0

[category_title] => EN - The land of We

[category_route] => oikonomia/it-la-terra-del-noi

[category_access] => 1

[category_alias] => en-the-land-of-we

[published] => 1

[parents_published] => 1

[lft] => 112

[author] => Luigino Bruni

[author_email] => ferrucci.anto@gmail.com

[parent_title] => Oikonomia

[parent_id] => 1025

[parent_route] => oikonomia

[parent_alias] => oikonomia

[rating] => 0

[rating_count] => 0

[alternative_readmore] =>

[layout] =>

[params] => Joomla\Registry\Registry Object

(

[data:protected] => stdClass Object

(

[article_layout] => _:default

[show_title] => 1

[link_titles] => 1

[show_intro] => 1

[info_block_position] => 0

[info_block_show_title] => 1

[show_category] => 1

[link_category] => 1

[show_parent_category] => 1

[link_parent_category] => 1

[show_associations] => 0

[flags] => 1

[show_author] => 0

[link_author] => 0

[show_create_date] => 1

[show_modify_date] => 0

[show_publish_date] => 1

[show_item_navigation] => 1

[show_vote] => 0

[show_readmore] => 0

[show_readmore_title] => 0

[readmore_limit] => 100

[show_tags] => 1

[show_icons] => 1

[show_print_icon] => 1

[show_email_icon] => 1

[show_hits] => 0

[record_hits] => 1

[show_noauth] => 0

[urls_position] => 1

[captcha] =>

[show_publishing_options] => 1

[show_article_options] => 1

[save_history] => 1

[history_limit] => 10

[show_urls_images_frontend] => 0

[show_urls_images_backend] => 1

[targeta] => 0

[targetb] => 0

[targetc] => 0

[float_intro] => left

[float_fulltext] => left

[category_layout] => _:blog

[show_category_heading_title_text] => 0

[show_category_title] => 0

[show_description] => 0

[show_description_image] => 0

[maxLevel] => 0

[show_empty_categories] => 0

[show_no_articles] => 0

[show_subcat_desc] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles] => 0

[show_cat_tags] => 1

[show_base_description] => 1

[maxLevelcat] => -1

[show_empty_categories_cat] => 0

[show_subcat_desc_cat] => 0

[show_cat_num_articles_cat] => 0

[num_leading_articles] => 0

[num_intro_articles] => 14

[num_columns] => 2

[num_links] => 0

[multi_column_order] => 1

[show_subcategory_content] => -1

[show_pagination_limit] => 1

[filter_field] => hide

[show_headings] => 1

[list_show_date] => 0

[date_format] =>

[list_show_hits] => 1

[list_show_author] => 1

[list_show_votes] => 0

[list_show_ratings] => 0

[orderby_pri] => none

[orderby_sec] => rdate

[order_date] => published

[show_pagination] => 2

[show_pagination_results] => 1

[show_featured] => show

[show_feed_link] => 1

[feed_summary] => 0

[feed_show_readmore] => 0

[sef_advanced] => 1

[sef_ids] => 1

[custom_fields_enable] => 1

[show_page_heading] => 0

[layout_type] => blog

[menu_text] => 1

[menu_show] => 1

[secure] => 0

[helixultimatemenulayout] => {"width":600,"menualign":"right","megamenu":0,"showtitle":1,"faicon":"","customclass":"","dropdown":"right","badge":"","badge_position":"","badge_bg_color":"","badge_text_color":"","layout":[]}

[helixultimate_enable_page_title] => 1

[helixultimate_page_title_alt] => Oikonomia

[helixultimate_page_subtitle] => La terra del noi

[helixultimate_page_title_heading] => h2

[page_title] => The land of We

[page_description] =>

[page_rights] =>

[robots] =>

[access-view] => 1

)

[initialized:protected] => 1

[separator] => .

)

[displayDate] => 2023-11-12 08:21:58

[tags] => Joomla\CMS\Helper\TagsHelper Object

(

[tagsChanged:protected] =>

[replaceTags:protected] =>

[typeAlias] =>

[itemTags] => Array

(

[0] => stdClass Object

(

[tag_id] => 191

[id] => 191

[parent_id] => 1

[lft] => 379

[rgt] => 380

[level] => 1

[path] => la-terra-del-noi

[title] => La terra del 'noi'

[alias] => la-terra-del-noi

[note] =>

[description] =>

[published] => 1

[checked_out] => 0

[checked_out_time] => 2023-09-23 08:53:08

[access] => 1

[params] => {}

[metadesc] =>

[metakey] =>

[metadata] => {}

[created_user_id] => 64

[created_time] => 2023-09-23 08:53:08

[created_by_alias] =>

[modified_user_id] => 0

[modified_time] => 2023-09-23 08:53:08

[images] => {}

[urls] => {}

[hits] => 12048

[language] => *

[version] => 1

[publish_up] => 2023-09-23 08:53:08

[publish_down] => 2023-09-23 08:53:08

)

)

)

[slug] => 19636:capitalism-a-new-catholic-spirit

[parent_slug] => 1025:oikonomia

[catslug] => 1168:en-the-land-of-we

[event] => stdClass Object

(

[afterDisplayTitle] =>

[beforeDisplayContent] =>

[afterDisplayContent] =>

)

[text] => The land of We/8 - The market, the merchants and the Gospel: scientific reflection and social works

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 11//11/2023

The era of the medieval merchants and of their companies where in the Book of Reason, the main account was listed under the name of "Messer Domineddio", was the time when the alliance between the merchants and the mendicant friars generated Florence, Padua or Bologna. It was an extraordinary era that failed to become the modern Italian and Meridian economic culture because the Lutheran Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation split Europe in two and prevented the medieval civil seeds from fully flourishing. It was, paradoxically, the Protestant Nordic world that gained a part of the legacy of the first medieval market economy (but without its charisms, without Francis and Benedict), although it was born in controversy with the wealth of the Roman Christianity of the Renaissance Popes. Catholic countries, including Italy in a special way, experienced the Protestant Reformation as a religious and civil trauma, and the results were typical of a major collective trauma. We cannot know what Italian and Meridian society and economy could have become if that alliance between Franciscans and merchants had continued after the sixteenth century, if the Catholic Church had not been afraid, at times terrified, in the face of any form of individual freedom, convinced that the "internal forum" without the control of the pastors was too exposed to the winds of heresy coming from the North. All that class of humanist merchants that developed between Dante and Masaccio, Michelangelo and Machiavelli, the businesses and banks of the Tuscans and the Lombards, shattered on the rock of the Council of Trent. With the end of the sixteenth century the Baroque age began which contributed some artistic and literary excellence but did not generate children and grandchildren equal to those first merchants who were friends of the friars and the cities. The Baroque history of Italy is the story of an interrupted path, of an unfinished civil, religious and economic history which had determining effects on the shape of the modern economy and society under the Alps. That set of theology, legal and moral norms, practices and prohibitions, fears and anxieties that we call Counter-Reformation (I do not use the expression of Catholic Reformation, even if there was a Reformation in the Catholic Counter-Reformation and a Counter-Reformation in the Protestant Reformation) has not only conditioned our religious life, it has also changed and shaped our businesses, politics, banks, communities, families and taxes.

[jcfields] => Array

(

)

[type] => intro

[oddeven] => item-odd

)