The land of We/5 - Soul of Civil Economy, Abbot Antomio Genovesi was persecuted for his ideas

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 21/10/2023

The debates around usury, which have accompanied many centuries of European history, are the tip of a very deep and vast iceberg, which directly concerns the common good, the poor and social justice. It was not, nor is not, only a matter for specialists in finance or economic ethics, but it is at the heart of the social pact and therefore of the life and wellbeing of communities. It should therefore come as no surprise that not only economists and theologians but also philosophers, writers and humanists have always written about usury.

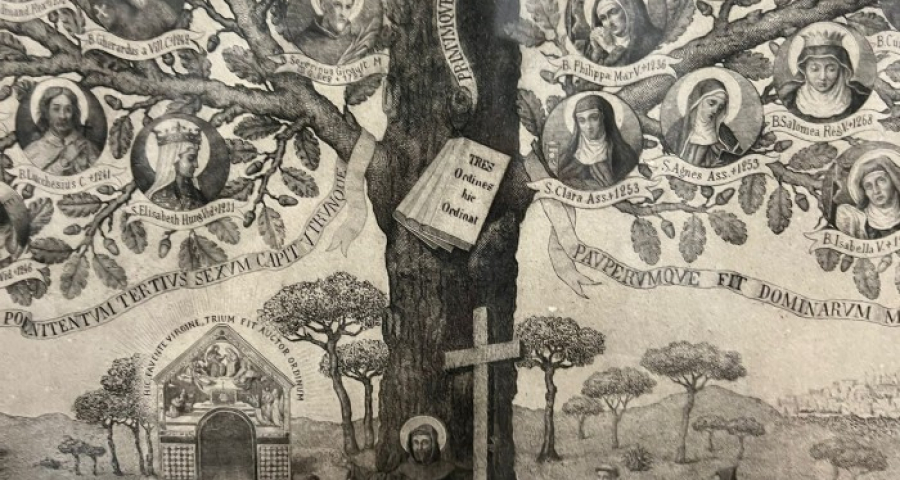

Luther's Reformation, and the consequent Catholic Counter-Reformation, also greatly influenced economic ethics and attitudes towards usury. Catholic theologians and preachers from the second half of the sixteenth century, very worried and at times even terrified by the harmful effects of individual freedom of conscience not mediated by ecclesiastical authority, created a capillary system of control of all ethically sensitive actions, including those related to economics and finance. And so, more or less intentionally, the doctrine on usury (and in general, on freedom of enterprise and profits) regressed by at least four centuries. They forgot the reflections of the Franciscan masters and brought the tenor and level of the debates and prohibitions on interests and profits, back to those found in the treatises of the end of the first millennium.

The mid-eighteenth century saw a new golden age of economic ethics. Authors such as Muratori and Genovesi resumed the debate on profits, money and interest where civil humanism had left it, and wrote beautiful pages. They did not omit the damage caused by of usury which they studied a lot, they opposed them, but they did not even forget the essentiality of credit for a new society finally free from the bonds of feudalism. And so the Civil Economy was born, one of the brightest chapters in Italian and European history and Abbot Genovesi was its soul.

Antonio Genovesi was first a theologian and then an economist. He did not have an easy life with the Church of his time, which removed him from teaching theology (1745) advising him to move to the chair of ethics. He was accused of atheism and heresy; he was much loved by students and people, but "he was persecuted so ferociously and beyond death if to avoid greater damage it was prudent to bury him secretly, without a tombstone and with the pitiful "complicity" of the Capuchins of Sant'Efremo Nuovo" (Lina Sansone Vagni, Studi e Ricerche Francescane 23, 1994). His Lezioni di Economia civile were included in the Index by decree of 23.6.1817. In his autobiography he wrote: "I, who had begun to be bored by these theological intrigues and who was beginning to have a horror of such turbulent and often bloody studies, did more: I took back my manuscripts and I resolved permanently not to think about these matters anymore (Autobiografia, lettere e altri scritti, p. 22).

The great theological difficulties that Genovesi encountered led him to become an economist, and to be the first to occupy a Chair of Economics. Teaching, studying and travelling around his Kingdom of Naples, he also wrote important pages on usury and money, where his theological and biblical competence was vital for him. His painful, forcibly diverse academic career produced some amazing pages. Let's look at some of them.

As a theologian, Genovesi was well aware of the philosophical and theological objections to the payment of interest on money, usury or interest, which he nevertheless distinguished (Lezioni, Vol. II, Ch. 13, §1) - but he knew that these abstract prohibitions had greatly complicated the lives of honest merchants and created a hypocritical Catholic culture, where no one could lend but everyone lent and borrowed. Hence his tenacious and free struggle to unmask these hypocrisies and modernize his people in Naples.

We find his theoretical and rhetorical masterpiece on usury and credit where he is in discussion with theologians, whom he calls ‘my enemies’: "Theologians therefore face two difficulties. 1. That the doctrine of usury is repugnant to biblical doctrines. 2. That it is opposed to the authority of the fathers and theologians’. On the second difficulty, it refers "to the learned work of the late Marquis Maffei", where it is shown "that it is not true, that the fathers and theologians were all of this opinion, as long as one knows how to explain the state of the matter" (§XIX). And then he confronts the theologians directly, with a wonderful style: "I would like to be in a council of those most learned and most holy fathers and ask them two questions. 1. If one, who is not in need, asks me for a benefit for pure luxury, for enjoyment, for greed or for wealth, am I, fathers, obliged to lend it to him? 2. And if I am in need, and I cannot I live except by asserting my own, can I say to this man, brother, let us help each other; I will grant your favour with my things, but you in return, will give me the current price of the loan; am I entitled to ask him this question? Until I hear the answer of this council to my two questions, I am certain that neither the fathers nor theologians were ever against usury or the terms of our question" (§XIX). Reading the quality of these ancient debates increases sadness in the face of the ‘quality’ of our talk shows.

Then he continues and enters the field of biblical exegesis, showing us a Genovesi who is a student of Erasmus and above all of Muratori, true pioneers of the scientific and free study of the Scriptures, who, we will see, goes so far as to rectify the official translations of the Gospels: "Let's start from the Old Testament. The law of Moses in Deuteronomy (23:20) is: "Non foeneraberis fratri tu pauperi; foeneraberis alienigeno" (you will not lend to your poor brother, you will lend to the foreigner). Let us develop this law. 1. He gives or leaves the right to give usury to those who were not Jews (this is the alienigeno or foreigner)". And from here he masterfully concludes: "Therefore he did not consider usury as contrary to jus and the law of nature. God does not annul the law of nature, because God can neither annul nor deny Himself. 2. He forbids usurious lending to the poor (Jewish) brother” (§20).

And so he formulates his general theory on lending and usury: "Therefore the main proposition is: you have the right to give usury to your brothers; the exception is, provided they are not poor." 20 This is his only solution: the Bible forbids interest on loans to the poor but does not condemn it in general.

After refuting his critics who quoted the Old Testament to deny any interest, he moves on to the New Testament. First of all, he carries out a very up-to-date and correct operation: he reads the gospel together with the entire Hebrew Bible. Thus Genovesi places Luke's famous phrase about lending without asking for interest (Lk. 6:35), which theologians used to condemn any interest, within the consideration he has just made on the book of Deuteronomy and therefore in the context of the prohibition of lending to the poor with interest. Genovesi paraphrases Luke 6:35 ff. and offers us a fascinating translation: «You do no good, he tells them, except to those from whom you hope to receive. Therefore, your principle is to do only what gains for you. Vile maxim that subverts humanity. All the rascals, the scoundrels, the greedy and the thieves, do the same. In what, then, will the grace that is given to you be placed? What gratitude do you deserve from God for this? You see these tax collectors lend to those, where they hope for more usury; you are no different to them if you too offer these crooked benefits to the poor to attract their substances to you? Therefore, if you want to be just and virtuous, as the Most High requires, and claim to be called his children, love your enemies too, do good to them: lend to them without disappointing the needy and the poor of the hope they have had in your generosity, and without making them despair». (§21).

And now comes his true stroke of genius (and culture). As a teacher of Greek and Latin, Genovesi gave his fellow theologians a lesson, still very relevant and worth further consideration. Let's see how. He said: “This precept is therefore in conformity with the first part of the law of Deuteronomy. Is there anything that favours our theologians?” (§21). Genovesi, however, realized that his translation took some liberties that may have seemed intrusive, that is, his discourse on the poor and needy. He wrote: "But let us account for some words that I have included in my paraphrase, which those who read the versions will believe to be intrusive. I said before that Jesus Christ speaks in the present place of the needy and the poor, which is not expressed in the precept” (§22). Genovesi maintained that the reference to prohibition was addressed to the poor because such was the original contrast in Deuteronomy (which Luke implicitly quoted), and I add, because these words come after the sermon of the Beatitudes that opens with ‘blessed are the poor’ (6:20). It should then also be noted that the Latin text of the Bible (the Vulgate) in that passage of Luke had the word ‘indiget’, that is‘ needy ’,‘indigent’, a word which was omitted in the Italian translation.

But the most beautiful, truly moving part of his courageous and innovative exegesis is on the word hope. Current translations, starting with the Latin Vulgate, translate apelpizo (the Greek word in Luke) with ‘without hoping for anything in return. Whereas Genovesi translated it differently and I include it here in its entirety: "I said: without disappointing the needy and the poor of the hope, which they had in your generosity, and without making them despair, because, although the compilers of the variants of the New Testament omitted it, some sacred critics have observed that using the accusative masculine, the απελπιζω (apelpizo) should be taken in an active sense and means not to cause despair, in which sense it is used by many of the best Greek writers". And so he proposes to also amend Jerome’s version (which here reads ‘nihil inde sperantes’: lend without hoping for anything): "The Latin version could have been: mutuum date, neminem desperare facientes" (§22), that is: lend, without making anyone despair! This is why Genovesi concluded his reasoning with these words: "Because this precept clearly speaks of lending to the poor and because it is more appropriate to the text, to read the verb apelpizo in the sense of not reducing anyone to despair" (§22). Awesome! Many years ago when I began to study and write about economics and then about ethics and finally about the Bible, I hoped that one day I would be able to find, understand, enjoy and help others to enjoy a difficult and beautiful page, like this one of Genovesi. Perhaps his biblical exegesis is not the best or the only one, but his economic exegesis of those biblical passages remains unsurpassed and full of civil hope.

Usury is a great social evil because it reduces people, the poor, to despair. The despair of the poor is the first measure of our usury, from that of some banks to that of an irresponsible civilization that plunders the earth and throws its children and grandchildren into despair.