The Market and the Temple/13 - The merchant writers hand down pages of life and economic stories in the name of competence, sobriety, beauty and faith to us.

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire le 31/01/2021

Our economy can only become civil and civilized when it becomes a relationship and learns how to unite different people and inhabit contradictions and ambivalences in a significant and generative way.

The spirit of the market economy between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was different, at times very different, from that of modern capitalism. The reason that it is important to return to the questions of that economic period lies in this difference, because in the subsequent centuries capitalism did not answer those same questions differently, it simply changed the questions. That first mercantile ethic developed within a world which, while it saw the wealth of the great merchants grow and sought a way to keep them within the enclosure of the sheep of Christ, also saw the Franciscan movement struggling with Popes and theologians in order to obtain the privilege of the most high poverty, of being able to cross the world without becoming domini (masters) of the goods they used. A constant tragic tension ran between the Book of Commercial Reason and the Book of Religious Reason. One challenging and limiting the other, and so trading did not become an idol and religion did not turn into a cage.

We cannot understand European economic ethics if we do not interpret it starting from these tensions and ambivalences, if we do not see the wealth within the poverty and the poverty within the wealth. Those merchants became very rich, but that wealth remained a wounded wealth, because, unlike what would happen in modern times, it was neither immediate nor evident that wealth was a blessing in itself, while it was immediate and evident that evangelical poverty was a blessing. However, even in this case, the paradoxes and ambivalences turned out to be highly generative.

We can also read it in the volume "Merchant writers" (“Mercanti scrittori” edited by Vittore Branca). Among these stories, "Memories"/“I ricordi” by Giovanni di Pagolo Morelli (Florence, 1371-1444) stands out in particular, where the reason for trading is perfectly integrated with the reason of family and with the reasons of state of the city of Florence. Morelli also gives advice and recommendations to his "pupils", children and grandchildren, a distillation of generations of mercantile wisdom ("Memories"/"I ricordi", III, p. 177). The first sense of a merchant, the really essential one, is touch. He must touch his products, because the decisive secrets behind mercantile knowledge are learned by touching the goods that are bought and sold. The clothes, the pieces of leather and the fabrics are known by picking them up in your hands, and handling them. The first meaning of a manager refers to the hands, to the stables, where a horse is tamed by the use of the hands. An entrepreneur who loses contact with the things he trades, who does not exercise touch (con-tact), who does not test them by touching them with his fingers, will lose competence and put himself in the hands of others, on whom he will end up depending entirely. In this, the division or delegation of labour does not apply: the entrepreneur must distribute the different roles, he can and must delegate extensively, but not the touch of his goods, this role he must keep for himself. The Italian entrepreneurs grew and developed by touching their goods. They were as, or even more, competent in the issues of their activity than their workers and technicians. This tactile competence was their first strength. Hence, it is obvious that this "capitalism" began its decline when it put companies in the hands of managers who no longer touched the things they bought and sold, because they were experts in tools, but almost never in the hands, touch and handling of the products of their business in question.

Furthermore, Sir Giovanni tells us that a good merchant must travel the world, visiting the markets of many cities in person. He will need staff and buyers, of course, but he will not become a good merchant if he does not acquire direct knowledge of the places and the people, if he does not associate with them directly. As long as an entrepreneur has the passion, energy, enthusiasm and desire to go to trade fairs in person, to see and meet with customers, suppliers and bankers "with his own eyes", he will still have control of his company, hold the reins in his hands, managing it ("Memories"/"I ricordi", III p. 178). If, on the other hand, he begins to spend his days only in meetings in an office and in five-star restaurants, even if he does not realise it, the end has already begun, because he has in fact lost the touch and the eyes for the art of trading.

Then, there is the second commandment of mercantile ethics: «Go ahead firmly and trust, but do not be gullible: the more someone shows himself in words to be loyal and knowledgeable, the less you trust them; and whoever speaks to you, making an offer, do not trust every point that he makes. The great talkers, braggarts and full of coaxing, enjoy hearing them word by word, but do not trust them at all. Those who have switched between multiple activities, companions or teachers, have nothing to do with them» (p. 178). When an entrepreneur begins to surround himself with "know-it-alls", chatterboxes, vain, great speakers, he has already entered his sunset avenue. But to recognize them you need to encounter them outside the golf courses and luxury hotels, because it is an ancient law of trading that you do not know a person until you see that person working. It is exceedingly naive to think that you will get to know clients or buyers in a conference. Work is the great sieve that discerns the chaff of mere chatter from the flour of good trade.

The third: «Never demonstrate wealth: keep it hidden and always give to understand in both words and deeds that you have half of what you own. By keeping this instinct and attitude, you will never be too deceived» (p. 178). Here, we are not so much faced with a tax evasion technique (but perhaps so, for some); there is more to it, an attitude, a whole lifestyle. Those early merchants were well aware that social envy is degenerative for everyone. Civil wealth must not produce envy, but emulation, that is, the desire for imitation. However, in a world of little social mobility, as the medieval one was after all, ostentatious wealth often only serves to create envy and conflict. Showing it off beyond any limits (and here the great theme of the lawful intensity of wealth returns) does not help anyone: «Do not brag about your great gains. Do the opposite: if you earn a thousand florins, then say you earned five hundred; if you trade a thousand, say the same, and if they are seen, say, "They belong to someone else". Do not cover yourself in expenses and bills. If you are rich of ten thousand florins, live as if you had five» (p. 189). Sobriety remained a great virtue for entrepreneurs and industrialists for centuries. Their children often went to school with the children of their workers, attending the same churches, weddings, and funerals. They were "gentlemen" but they were also com-panions, at least their children were companions of ours. When, a few decades ago, competition shifted from production to consumption, the centre of capitalism shifted from the entrepreneurs to the managers, and capitalism became a huge ostentatious mechanism producing a lot of social envy and frustration, especially in times of crisis.

In his "Book of good habits" ("Libro dei buoni costumi"), Paolo da Castaldo (1320-1370), gives a lecture on a fourth pillar of that same business ethics: «Always have the best and most sufficient elements. And do not look at the cost because "a good rent or wages for good staff was never expensive"; the bad ones are the expensive ones» (p. 34). Infinite wisdom, which we have forgotten in a capitalism where a manager's high salary is the first and often only indicator of his quality. Paul reminds us here that the "bad element" is expensive because he is generally more interested in money than in trading, and that a much too elevated salary can thus become a mechanism of adverse selection of people.

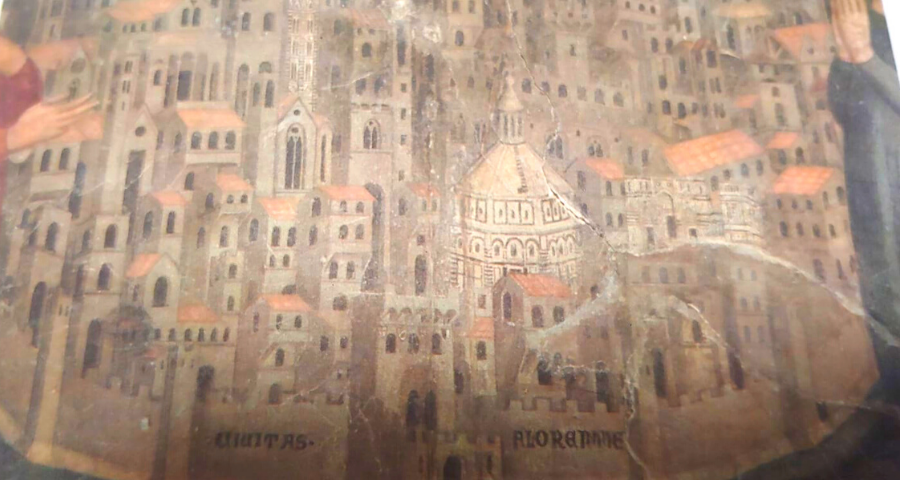

The fifth: «Make sure that what you have done well is written down in your books, do not forgive the pen and explain yourself well in the books. And you will live free, feeling safe and firm in your valsente (capital)» (p. 178-9). "Writing beautifully" is the merit of a merchant, in the words of the merchant and poet Dino Compagni ("The Chronicle and the Song of Merit"/("La Cronica e la Canzone del Pregio"). We would not have had Italian and European civil humanism without the beautiful writing of the merchants, and we would not have had their extraordinary commercial success without the care and esteem for writing and letters: «The pupil should strive to be virtuous, learn science and grammar, and let him learn a bit of abacus» (p. 192). This does not mean that the merchants were (or should be) teachers or professors. The fine writing of merchants is different from that of professors, but it is good and necessary for the common good. Florence was capable of centuries of extraordinary economy, because the merchants nourished poets and artists with their wealth, but Dante and Boccaccio nourished the merchants with their beauty, which thus entered the books of reason and that fascinating speech that enchanted the whole world. Merchants in turn enchanted them with beautiful fabrics, but also with poetic words, with their beautiful speaking and writing.

Finally: «In conclusion, these above-mentioned things are useful for becoming an expert and tending to the world, for making oneself well liked and being honoured and respected» (p. 196). Benevolence, good reputation, honour and esteem were invisible but essential goods, more so than profit. Wealth obtained with bad a reputation was worth nothing. The second paradise that those ancient merchants sought was a legacy of good reputation and honour to be left to their children. Dying rich and dishonoured was their real idea of hell. Without taking the matter of good reputation into consideration, we cannot understand the phenomenon of the sale of indulgences. When nearing death, those merchants and bankers donated a large part of their assets to the Church or the Municipality, they did not do it just to spend less years in purgatory; they also wanted to avoid the hell of bad fame on earth - for them and for their families. While we are leaving public debt to our children, the legacy of the ancient merchants was also fame and honour.

All the ambivalence of those first merchants, but also their "virtue" and their honour, lies behind our "capitalism" still supported by families, and despised because it sometimes risks becoming "familist". The conjunction "and" played a decisive role in our first economic and social humanism: money and God, spirit and merchandise, beauty and wealth, luxury and poverty. Words that collided and clashed, and somewhere in between life was born. We are still in need of a conjunction, certainly very different from the medieval one. Our economy, however, will become civil and civilized only when it becomes a relationship and learns how to unite different people and inhabit contradictions and ambivalences in a significant and generative way.