How to teach the correct use of money to children? Here are four rules that might be useful in the family...

By Luigino Bruni

published in Il Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 04/12/2022

The use of money within primary relationships is always very delicate, especially in the family, where children, teenagers and young adults enter the money game. It may be useful to follow four rules, supported by the research of economic science and by practice.

Rule number one. The money must come from the parents; they are the sole administrators of the family money. And even when external donations come in (for confirmations, birthdays...) these must be known and managed by the parents. The Adventures of Pinocchio tells us very clearly: the money that lands in Pinocchio’s hands only causes him trouble. Once children pass the age of 10, it becomes difficult to give them gifts that they appreciate, and the temptation to give money is strong. This practice almost always becomes a shortcut because there is no time to choose a gift together, because we do not know our children well enough, because we do not have time. Grandparents love to open bank accounts and insurance policies for their grandchildren. Let them do it, but don't let them tell about it to the grandchildren: encourage them to express their love in other forms.

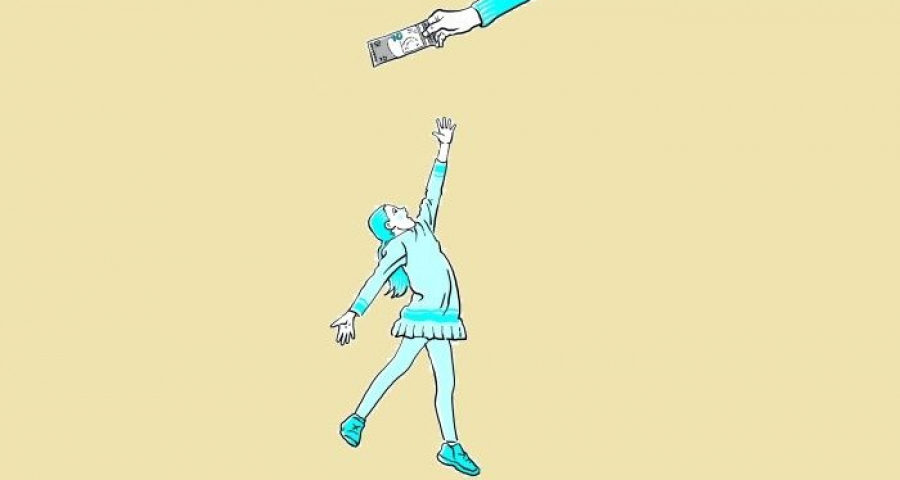

Rule number two. Do not use money as an incentive to get something from your sons and daughters. They must be motivated, of course, but within their home and from an early age they must be taught the art of gratuitousness, not the art of commerce; they will have time for the latter throughout their lives, and it will only be a good art if it rests on the art of gratuitousness. Because the family (along with the school) is the first place where one learns that there are beautiful and good things that must be done not because of the reward they give us, but because these things are beautiful and good. It is the education of “and that’s all” that really counts when you are young. So it is quite a bad thing to make a price list at home (2 Euros for doing the dishes, 3 Euros for walking the dog...) or to invent the “pocket money for good grades” invented by an economist colleague of mine (that he later regretted, when he saw that his daughter did nothing without being paid: but it was too late, he had created a homo oeconomicus in skirts).

Rule number three. Pocket money, which a certain dominant economic culture is introducing into families, is dangerous. Pocket money is recommended by many experts because it is seen as education for responsibility. What studies show instead is that pocket money tends to increase a mercantile attitude towards life and friends in children, and also towards themselves. And this is serious: if we do not learn as children to place an intrinsic value on what the ancient world called virtues, once we grow up we will be bad workers that will only work if and when there is a “carrot and stick”.

Rule number four. Learn to develop non-monetary rewards. Rewards are important with young ones because they reinforce good behaviour. But only as long as they do not become an incentive. The reward, if non-monetary and symbolic (a trip, a gift, or even a hug...), recognises that the action done is good: it is not a contract, the price is not defined before the action is done, it is not always there but only sometimes, and it changes over time. Rewards reinforce gratuitousness, incentives erode it.

Our capitalism is turning all pacts into contracts and all rewards into incentives. Let us at least protect the family from this invasion, let us keep the innocent temple of children's hearts free of merchants. Many mistakes are made in this field due to a lack of thought and attention, especially on the part of pedagogues and moralists, who have always underestimated the economic weight in the education of children. We must devote more time to economics, if only to guard against its mighty and powerful logic.

Photo credits: © Giuliano Dinon / MSA Archive