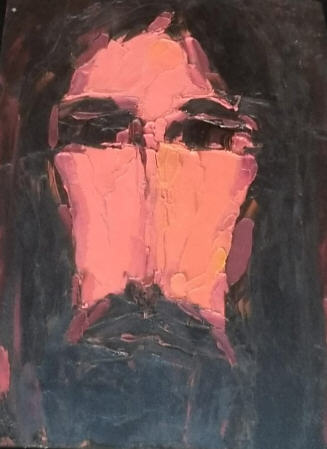

Greater than Guilt/27 - Let’s learn to find God where he isn’t supposed to be

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 22/07/2018

“I will not urge thee, - no nor, if thou yet shouldst have the mind, wouldst thou be welcome as a worker with me. Nay, be what thou wilt; but I will bury him... But if thou wilt, be guilty of dishonouring laws which the gods have stablished in honour.”

“I will not urge thee, - no nor, if thou yet shouldst have the mind, wouldst thou be welcome as a worker with me. Nay, be what thou wilt; but I will bury him... But if thou wilt, be guilty of dishonouring laws which the gods have stablished in honour.”

Sophocles , Antigone (English translation by R. C. Jebb)

The story that Samuel's books tell us is a succession of murders, fratricides, incest, rapes and brutal violence. YHWH, the protagonist of many biblical pages, here seems to stand away from the fray, observing the spectacle of death offered to him by people. Yet the Bible, in all its books, continues to speak to us about God, containing his words and his Word. But where? And how?

Many readers, yesterday and today, look for it and find it in the few intense prayers of David, in the wise words of women, in the rapid apparitions of prophets, and discard all the other words that are uncomfortable, scandalous, too human to be divine. But if we look well and differently we might find that the biblical God can also - and perhaps above all - be detected in his absence and in his silence. Next to Tamar, the sister raped and then driven away; in the battlefield, crying with David for the death of Jonathan; in the woods, consoling Absalom entangled in the trees; on the way of the cross, along with Simon of Cyrene; under the cross of a son. The Bible speaks to us about its God even when it is silent, when it does not speak about him and when it does not make him speak. As in every love story, where the decisive words are those that we have never said because they had become flesh - and the flesh is mute. The biblical God does not allow himself to be trapped by biblical words, he speaks when he is silent, he is silent when he speaks, he speaks where he seems to be silent, he is silent where he should speak. And so he protects himself from our continuous and tenacious attempts to turn him into an idol, or to idolize the Bible. But if we learn to find God where he should not be - in the Bible just as in life - we will realise that we have many more words to try to pray to God and talk to people.

Absalom died, killed by Joab's spears while he was hanging from the tree. Now Joab must bring the news to David, who had asked him to treat that son "gently”. The choice of the messenger is not simple. Eventually Joab sends a Cushite (18:19), an ambassador by penalty. When the king asks him: “Is it well with the young man Absalom?” (2 Samuel 18:32), the Cushite announces to him the sad news. David’s reaction is strong and full of pathos:

“And the king was deeply moved and went up to the chamber over the gate and wept. And as he went, he said, “O my son Absalom, my son, my son Absalom! Would I had died instead of you, O Absalom, my son, my son!” (18:33) David is dear to the Bible for many things, but also and perhaps especially for his heart capable of genuine and true feelings, the ones we can recognize and appreciate because they are too similar to ours. He had to make a civil war to reject Absalom’s conspiracy who proclaimed himself king, but the text tells us that he did not want the death of that young son. David finds himself, once again, in a conflict between two fundamental dimensions of his life. He is torn apart by the tension between the king who must reject an enemy to save his throne and kingdom, and the father who would not want the death of his son, the most beautiful of all the children of the people (for a parent each son is "the most beautiful of all", because without this generous and exaggerated look he would not be beautiful enough for anyone). These identity conflicts that take place within the same person are decisive, and much more concrete and real than interpersonal identity conflicts, which our culture, however, tends to amplify because it cannot recognize nor, much less, take care of conflicts within our souls.

The biblical text tells us that at the beginning the father prevails over the king, and in his words we re-read the many similar words of fathers and mothers in the face of the death of their young one. We find the expression "my son” seven times, a number that expresses infinite pain, because the pain for a child that is no longer there is always infinite. David was an experienced man of arms, he knew the craft of war very well, and so when he left Jerusalem to prepare for battle he knew that the death of Absalom would be the most likely outcome. Yet he had tried to change that destiny, to force the ruthless codes of war, and so he had asked for a special, “gentle” treatment for his young one, even though he knew Joab and the ruthless rules of the game of war very well. That's why the first thing he asks of the messenger is about his son. He was almost certain about what the terrible answer would be, but he still asks that question, clinging to the thread of hope contained in that almost. Like us, when we cling onto the "almost" of a medical report or the "almost" with which we open that final email answering our desperate request to try again a last time. We know, we are almost sure of the bad news, but we do everything to lengthen the duration of that almost, to try to steal a few hours or a few seconds from death. Then, when the time of desperate hope is over, we suddenly realize that we have only been cultivating an illusion, because the conclusion of the story was already inscribed in many facts and actions that we knew about, but we could not help but believe in that almost: “It was told Joab, »Behold, the king is weeping and mourning for Absalom«” (19:1).

For millennia, mourning was among the most precious know-how that cultures had accumulated and preserved to prevent wives, husbands, parents and sisters from "dying" together with their deceased one. Mourning is the transformation of unbearable pain into possible pain through the creation of relational goods. It is therefore an exquisite community operation, where my pain truly becomes our pain. Compassion means that the crying of friends and relatives whom we love does not increase our pain but reduces it. Over the course of a couple of generations, the West has forgotten the thousands of years of the community art of mourning, and so we have become infinitely vulnerable to the greatest pain again, which can kill us uncontested in the solitudes of our homes, mobile phones and computers.

David's mourning soon clashes with the interests of the state. His crying for Absalom discourages and depresses the army that had just emerged victorious from the battle: “So the victory that day was turned into mourning for all the people... And the people stole into the city that day as people steal in who are ashamed when they flee in battle” (19:2-3). The pietas of David, who cries for his son as father, came into conflict with the king David who had the duty to honour and not humiliate the troops who had fought for him. And while at the announcement of the messenger the father had prevailed over the king, now the public virtue of the sovereign wins over the private virtue of the father. Virtues are not always aligned with each other, and often come into conflict in the border zones. Another "victory" achieved, thanks to the hand of Joab: “Then Joab came into the house to the king and said, »You have today covered with shame the faces of all your servants, who have this day saved your life and the lives of your sons and your daughters and the lives of your wives and your concubines, because you love those who hate you and hate those who love you. For you have made it clear today that commanders and servants are nothing to you, for today I know that if Absalom were alive and all of us were dead today, then you would be pleased«” (19:4-6). With enormous strength, Joab shows him another side of reality, a very hard one, reminding him that his first fatherhood is the one towards the people. The king is not a man like everyone else, he is a collective personality, a symbol, his behaviour is always and inevitably an immediate message to the people. He can't have and show feelings like all other human beings. He must put the common good before his private good. We do not know how much Joab was interested in the good of the king and the people, or whether in reality he was interested above all or only in the good of the "commander" Joab. It is certain, however, that his reasoning has its own logic and coherence, which are the only ones present and operating in the world of Joab and in that of the political power of all times.

That’s why Joab can add: “Now therefore arise, go out and speak kindly to your servants, for I swear by the Lord, if you do not go, not a man will stay with you this night, and this will be worse for you than all the evil that has come upon you from your youth until now” (19:6-8). Joab speaks to his king with great authority, which David recognizes: “Then the king arose and took his seat in the gate” (19:8). David listens to his general, but that lack of "gentleness" for the young Absalom does not remain unpunished. He appoints Amasa, the defeated commander of Absalom’s troops as the new army chief in place of Joab (19:14). Joab doesn't say anything but, here too, he acts immediately. And so, during the war to quell the attempt of the tribes of the North (Israel) led by Sheba to secede (20,1), Joab commits another one of his crimes. The two generals meet; Joab approaches Amasa and tells him, “»Is it well with you, my brother?« And Joab took Amasa by the beard with his right hand to kiss him. But Amasa did not observe the sword that was in Joab's hand. So Joab struck him with it in the stomach and spilled his entrails to the ground” (20:9-10). Joab offers Amasa his unarmed right hand and strikes him in betrayal with the left. Then he leaves him there half dead on the road “wallowing in his blood”. A man from Joab’s army “carried Amasa out of the highway into the field and threw a garment over him” because “anyone who came by, seeing him, stopped” (20:12).

We also stop and look at this other abandoned victim in that field, left unburied. But on that path of war another theophany is accomplished. YHWH returns to the scene in the murder of this man called brother and kissed, then left half dead along the way. We can look at that bloodied man, and then continue the journey together with Joab’s army, and so we add our part to the other twenty-nine. But we can also stop and help YHWH to bury another man betrayed by a kiss.

download article in pdf