The soul and the harp/ 5 - Tomorrow comes in innocence, blesses today and changes its name

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 26/04/2020

The city rejoices over the prosperity of the just, while there is celebration for the ruin of the wicked. The blessing of just men makes a city prosper; the words of the wicked destroy it

Book of Proverbs, chapter 11

The temptation to apply our economic and juridical ideas of justice to God is as always strong in us. The Bible, however, reminds us of gratuity.

«Listen to my words, Lord, consider my lament. Hear my cry for help, my King and my God, for to you I pray» (Psalm 5,1-2). An innocent man is accused of a crime. He tries to defend himself, in vain. He has exhausted all the degrees of judgment by way of human justice, but he still has the judge of last resort left. He gets up early, anticipating sunrise, and goes to the temple to present his "cause" to God. He only manages to whisper a few syllables, to merely utter a whisper with the last moral strength left in him: «In the morning, Lord, you hear my voice; in the morning I lay my requests before you and wait expectantly...» (3). Consider my lament. In these last hearings of life the only thing left is enough breath for a whispered lament. There is no more human prayer than a whispered lament mixed with tears. The whisper of a humiliated and tormented man is the purest form of prayer that moves both heaven and earth. And it is the most beautiful secular and human prayer that we can say to each other as well, when only those who are able to whisper from pillow, to fan, to heart can consider whispers as precious as life itself.

This man knows he is innocent, and denounces and condemns the wicked who have unjustly defamed him: «For you are not a God who is pleased with wickedness… You hate all who do wrong… The bloodthirsty and deceitful you, Lord, detest» (Psalm 5,4–6). Then he praises God who listens to him: «But I, by your great love, can come into your house… Lead me, Lord, in your righteousness because of my enemies - make your way straight before me» (Psalm 5,8–9). Beautiful image that of the paved way or road. Justice is also righteousness, that is, the art of making streets straight, of clearing obstacles, of removing all hurdles, that is, all scandals. The road of a poor man is dotted with rocks and obstacles. Laws and decrees of the powerful, tricks. Justice should pave his way and make it possible for him to walk freely. Good human history is a progressive transformation of rough roads into straight ones and then a continuous maintenance of these adjusted roads because as we get distracted they immediately fill up with stones and scandals again.

The man in Psalm 5 uses a typical rhetorical structure found in the psalter: “they ... but I”. They are fools and liars ... but I am innocent. What is the meaning of this: "but I"? A first reading of these verses would lead us to say that the biblical God answers prayers by virtue of the justice held within the one who prays. The intervention of God's justice would hence be a response to human justice. Only the righteous are heard in their prayers. Many think so, many have always thought so, because we tend to attribute the same characteristics to God as to good human judges. Crimes and penalties, merits and rewards. We love justice so much that we cannot imagine a God who is any less righteous than we are. And so, first we create a divine justice "in our image and likeness", and then, once created, we use this "divine" justice to give a sacred chrism to our human justice, in order to condemn others with the blessing of God, to the point we have reached today where meritocracy is being founded on the Bible and the Gospels. We have always done it, and we continue to do so. We know the economic and legal laws and unwittingly forced God to become both a merchant and a judge.

However, there is also a second possible reading. It is one, which does not place the reason for listening to a prayer onto the merits or faults of those who pray but in the gratuitousness of God. Are we saved because we are good or do we become good because we are saved? This is the ancient question at the heart of biblical faith. St. Paul quotes Psalm 5 (verse 9 on the malice and lies of others) to say something that goes in the direction of this second interpretation: «There is no difference between Jew and Gentile, for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and all are justified freely by his grace» (Romans 3,22-24). Everyone is justified freely by his grace. An epochal revolution and still unfinished, because the temptation to read the good things that happen to us as a reward for our merits and the bad things that happen to others as a result of their faults is too strong in us. Because we like gifts, but we like to think of ourselves as worthy of gifts to an even greater extent. However, if God were restricted to the perimeter of our ideas and concept of commercial and juridical justice, we would not have anyone anywhere capable of making what we already call just, within that just which is not yet called by this name, evolve.

If, and when, communities force God to be righteous in the shape and form of their human justice, they self-confine themselves in ethical traps that prevent their and God's justice from improving. These are those cases frequently found in religions, in which a narrow theology ends up restricting human beings. The Bible and its God, on the other hand, grew together with the interpretations that men and women gave to divine justice. This too is reciprocity between heaven and earth.

The same biblical pages, the same psalms, have said different things to different generations of readers. And not so much nor only due to the development of exegetical techniques, but because the evolution of our ideas of justice and love have changed and enriched the questions we have learned to ask God and ourselves, hence those ancient biblical words have learned new and different words from the real suffering of men and women. The Bible is logos and dia-logos (dialogue), it speaks to us only if we ask questions, and waits for us to repeat them every day: "come out".

Each generation understands the "sacrifice" of Isaac and the passion of Christ based on the growth of the ideas of justice that has been able to generate and resurrect itself from his wounds. Today we say different things – and we have to - about fathers, children, about the feelings they feel when faced with Golgotha and Mount Moriah, because we have had thousands of years to understand what dying and rising is. And if we learn new things about life, the Bible can also learn within us, and is thus able to tell us things that it could not have told us two thousand years ago, nor yesterday. In order to grow, the biblical God needs both us and the growth of our justice. The parable of the good Samaritan who takes care of the "half-dead" man has always said new things after each war, after each epidemic, after each time we arrived "half-dead" to an E.R. unit; and today, when doctors and nurses have expanded the semantics of the expression "to take care of", it will be able to say other new things again. Perhaps we needed two months of closed churches and suspended liturgies to understand the words of the Gospel of John differently, in this hour: «Yet a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Father in the Spirit and in truth» (John 4,23)

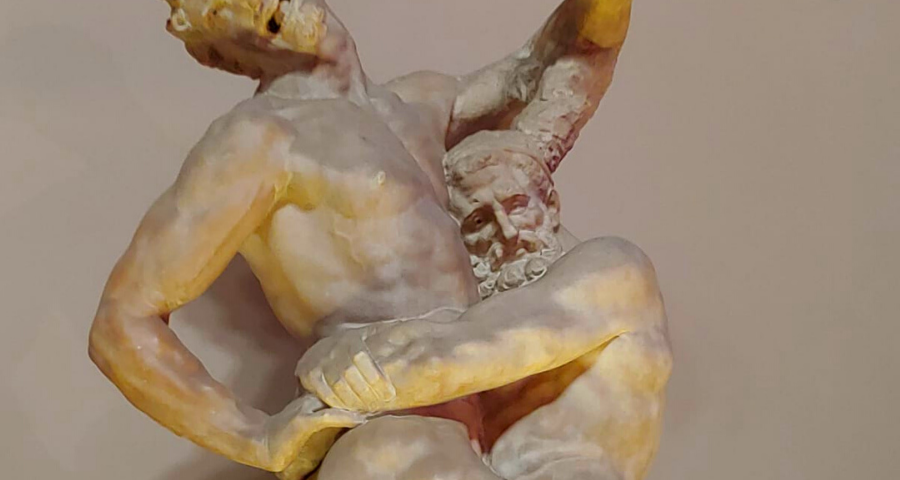

There is much of Job's song in the songs of the Psalter. Our canon places the Psalms after the Book of Job, because we do not understand the Psalms without reading them in the company of Job, if we do not sing them from his pile of manure, if we do not intone them outside the walls, excommunicated just like he was, condemned by friends, speaking to a God who takes his time before arriving. Job also turned his landfill into a courtroom; he brought his "cause" to God in the morning as well: «But I desire to speak to the Almighty and to argue my case with God… Indeed, this will turn out for my deliverance» (Job 13,3–16). Hence, by reading the cause of the psalmist together with the cause of Job we are once more able to learn something new about their God. The author of Psalm 5 brings his cause to God, and ... "waits"; Job asks God to come down from his throne to be a guarantor of his innocence, and ... waits. Both have their innocence in common and both share the same expectation for a different kind of justice. We do not know if this greater justice eventually arrived for the protagonist of Psalm 5, it is not the Psalter's job to tell us the epilogues of the events of its characters. However, we do know how Job's prayer ended. Despite his innocence, Job’s God did not show up to their appointment, and when in the end, he did arrive; he was not the god that Job had been waiting for. For the God of Job did not arrive, but that of his friends and their theology, a god who proved to be much too small compared to Job's righteousness which had grown along with his wounds.

Hence, a message that has been hiding in these biblical pages is the blessing of waiting. Faith in a different and higher justice generates the non-vain hope that tomorrow the Messiah will truly arrive and that we will know how to recognize him as we would recognize a friend, because we have waited and desired him. The day of the Messiah is tomorrow, but that tomorrow blesses our today changing its name. Our generation not only lacks faith, it lacks above all the hope and desire of waiting.

This endless expectation in history is not exclusive to a club of the innocent and righteous. It is also that of the wicked and sinners, because it can always infiltrate itself in one of the slivers of innocence that every man experiences at least some bright days of his life – Cain and Judas too, and therefore me as well, although I must always fight the invincible temptation to identify myself with the right and just side of the psalms. Our goodness is greater than our sins.

In a different time, a different day, a different man in crisis and depressed who wanted to die under a broom bush, was saved by a whisper, by a «still small voice of silence» (1 Kings 19).

That time it was God who learned how to whisper, and that whisper reached Elijah's ear and raised him up. What if a prayer were simply an encounter of whispers?: «Surely, Lord, you bless the righteous; you surround them with your favour as with a shield» (Psalm 5,12).

Download pdf article in pdf (411 KB)