The soul and the harp/12 - The Lord is on the side of liberation, not condemnation

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 14/06/2020

"Howl, howl, howl, howl! O, you are men of stones: Had I your tongues and eyes, I would use them so. That heaven's vault should crack"

William Shakespeare, King Lear

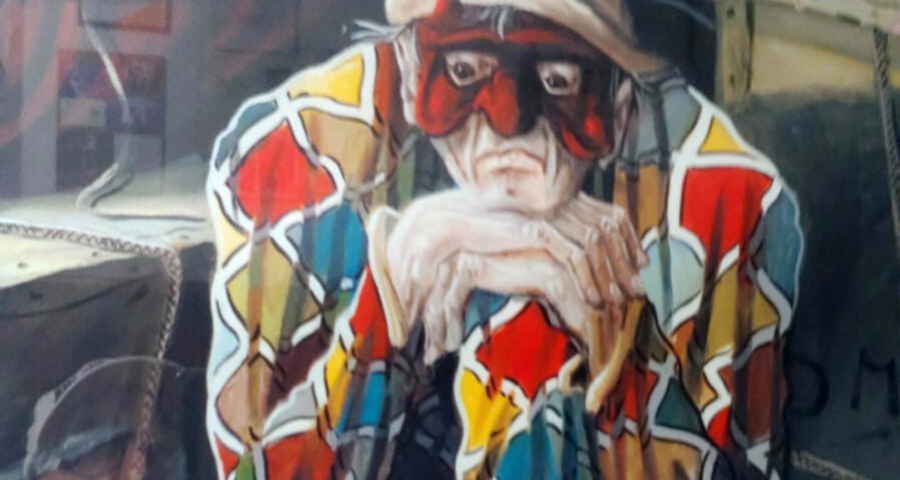

Psalm 22, one of the poetic and spiritual highpoints of the Bible, is also the pentagram on which the symphony of the passion of Christ was written. And it helps us understand something about crucifixes and their mystery.

A man is persecuted, tortured, humiliated and despised by other men. He feels death is near. That man is innocent - like so many others both back in the day and today. He knows he does not deserve that great pain, that violence, those humiliations - who does? However, in addition to being a suffering and humiliated righteous man, this man is also a man of faith. And right there, on that dark night, perhaps in a prison, over a pile of rubbish or inside a cistern, a prayer is born, a last desperate song emerges within his soul. Beginning with words that should be counted among the most precious, tremendous and stupendous in the Bible, among the greatest and most beautiful and stupendous in life: «My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?» (Psalm 22,1). A poetic, spiritual and anthropological highpoint in the Psalter, perhaps the greatest one

Yet another prayer opening with a cry, as in Egypt, when the first collective prayer of the enslaved people was another cry (Exodus 2,23). Many great prayers take the form of a cry, of a shout thrown out and up to the heavens in an attempt to awaken God. In the Bible, crying out and shouting is possible, lawful, and even recommended, it is a language that God seems to understand. By shouting out, we can awaken God, and remind him of his "work" as a liberator of slaves and the poor. As long as we are able to shout out our abandonment, we have not lost faith, we are only exercising it, merely carrying it out.

That tortured man, that "suffering servant", shouts out and experiences his misfortune in faith, and therefore within that general state of abandonment, he feels that God has abandoned him as well. And that cry becomes the rope or thread (fides in Latin) so stay in touch with God, that golden thread of life that does not break precisely because we dare to shout out. That man does not accuse God of having reduced him in that condition; unlike Job, he does not consider God his executioner. Instead, his pain arises from the non-intervention of God, who should intervene as the liberator of his faithful innocent, but still does not: «My God… Why are you so far from saving me, so far from my cries of anguish?» (Psalm 22,1). To awaken him, that man resorts to the best strategy in the Bible: he reminds God who he is. He helps him to remember his promise: «Yet you are enthroned as the Holy One; you are the one Israel praises. In you, our ancestors put their trust; they trusted and you delivered them. To you they cried out and were saved; in you they trusted and were not put to shame» (Psalm 22,3-5). In any relationship you wish to save, the first prayer is not: "remember me", but: "remember you", and therefore "remember us".

In the Bible, memory is the ultimate, most efficient resource available. We return to yesterday's events to recreate the faith of today and tomorrow. And the question of who is God immediately becomes a question of the deeds he has done, and not mere generic and anonymous actions but the specific and concrete actions within the real existence of those who are praying, shouting out, trying to awaken him. In biblical humanism, history is the first proof that its God is alive: the history of the people, but also the history of each single person. Each believer has his own Egypt, his own Red Sea and his own Sinai to narrate and to bring as a demonstration of the non-vanity of his faith. Each prayer is therefore, an encounter of three different "remember": we pray to God to remember himself, to remember us, and we pray to ourselves to remember God: «Yet you brought me out of the womb; you made me trust in you, even at my mother’s breast... From my mother’s womb you have been my God» (Psalm 22,9-10).

It is you: I never get quite used to the intimacy and confidence with which men turn to their God in the psalms. In that ancient, violent, often primitive world, God was their most delicate and secret "you", He was their friend, lover, beloved, love. Repeating the psalms generation after generation, day after day, hour after hour, we learned to pray, getting to know God better and getting a deeper knowledge of man and woman as well. However, we also learned the tenderness and confidence that exists between us, the cheek-to-cheek dialogue, because that "Lord of armies" also knew how to become tenderer than a child, than a bride, than a mother.

«But I am a worm and not a man, scorned by everyone, despised by the people. All who see me mock me; they hurl insults, shaking their heads. “He trusts in the Lord,” they say, “let the Lord rescue him. Let him deliver him, since he delights in him!” (...) All my bones are out of joint. My heart has turned to wax; it has melted within me. My mouth is dried up like a potsherd, and my tongue sticks to the roof of my mouth; you lay me in the dust of death. Dogs surround me, a pack of villains encircles me; they pierce my hands and my feet. All my bones are on display; people stare and gloat over me. They divide my clothes among them and cast lots for my garment… But you, Lord, do not be far from me» (Psalm 22,6-19). No other words are needed. Any further comment falls flat. But we cannot silence a resurrection, all resurrections need to be announced: «He has listened to his cry for help!» (Psalm 22,24).

He who was abandoned awakened God. Once again, a cry from an innocent man had pierced the sky: «I will declare your name to my people; in the assembly I will praise you... For he has not despised or scorned the suffering of the afflicted one... The poor will eat and be satisfied; those who seek the Lord will praise him - may your hearts live forever! All the ends of the earth will remember and turn to the Lord!» (Psalm 22,22-27).

Praise becomes universal, cosmic, infinite prayer in space and time. One of the most sublime and wonderful fruits of any great misfortune that we overcome is a soul enlarged to cover the whole universe. We become mothers and fathers of humanity, a new fraternity with everyone, both good and bad, is born, we all feel very small and yet sovereigns of the world.

A different innocent man, on a different day, was captured, tortured and sentenced, his feet and hands were pierced, and he was nailed onto wood. Whoever collected and narrated that man's passion could not have found a more suitable text in the Scriptures than Psalm 22, to make it the pentagram on which to write the symphony of Golgotha. At the height of Christ's life and passion, we come face to face with another cry, dressed in the words of Psalm 22: «My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?» (Mark 15,34; Matthew 27,46). It was an extraordinary, ingenious choice, all gift. The evangelists knew that that passion was not the same passion that that anonymous psalmist had experienced centuries before. Yet they were not afraid to bring back that scandalous song - a Man-God who cries out the abandonment of God. They did it because they wanted to tell us something important. If those disciples chose Psalm 22 to convey some part of their understanding of the passion and death of Jesus, then the idea of God at work in that crucifixion must be very similar to the God of that ancient psalm. They wanted to tell us that to understand that abandonment and that cross we must take Psalm 22 very seriously.

The man in the Psalm truly felt the abandoned by God. He was not pretending, the sense of abandonment was real. The same was true for Jesus. The man of the Psalm remained a man of faith within the realms of his passion, he did not lose faith. Neither did Jesus. That man did not protest with the Father accusing him of his suffering, but prayed to him to intervene within that suffering. And God replied, carrying out his job as liberator and savior, and raised him from his "death". Choosing Psalm 22 then means distancing yourself from many ancient and modern theological readings of the death of Christ. First of all, the psalm tells us that the cross of Christ was not intended by God as a "price" to be paid in order to save us. The psalmist knows that it was not God who led him to the gallows, but begs him to release him. God is on the side of liberation, not condemnation. Furthermore, the first Christians did not see and experience the cross of Jesus as a sacrifice of the Son wished for by the Father, because in that Psalm the psalmist does not say that God likes his suffering, in fact he says exactly the opposite. Finally, that passion and that cross are not seen as a voluntary sacrifice of the Son: the psalm tells us exactly the opposite, the suffering man asks God to free him from that unjust pain, and obtains that liberation. The biblical God does not want the suffering of his children.

Psalm 22 is also the Psalm of the resurrection. It tells us that the resurrection is the Father's response to the Son's prayer. As it tells us that, although the resurrection of Christ was a special and unique event, it is also true that what happened between the Via Crucis and the empty Sepulcher had some similar elements to what the ancient psalmist had experienced. And to what many already had experienced, wounded, humiliated, crucified and resurrected men and women, to the miracles that happen to us when we find ourselves on a mountain, we feel like worms, but we do not lose faith (at least that remains in our innocence), and suddenly we find ourselves risen. What Christ experienced was very similar, perhaps identical to what was experienced by the many crucified men and women throughout history - and therefore no crucifix in history remains outside the blessing framework of the Psalm, Golgotha, and the empty Sepulcher. And when the pain does not pass and resurrection does not come, we are allowed to cry out by borrowing the words of Psalm 22: let us sing it once, twice, a hundred times. If the angel of death finds us with those words on our lips or in our hearts, a resurrection will begin in his arms - many Bibles have been seen in the intensive care units of the pandemic spring of 2020, some open precisely on the pages of the Book of Psalms.

If the crying out of Christ on the cross is the beginning of Psalm 22, then we can imagine that that Psalm was the prayer of Jesus on the cross. Let's follow him in his secret song: «My God… why are you so far from saving me, so far from my cries of anguish?... But I am a worm and not a man, scorned by everyone, despised by the people. All who see me mock me… They pierce my hands and my feet. All my bones are on display… But you, Lord, do not be far from me. You are my strength; come quickly to help me… You brought me out of the womb; you made me trust in you, even at my mother’s breast». And finally, that last whisper: «You are my God».

Download pdf article in pdf (403 KB)