Economic Soul/4 - The project to create a credible Christian alternative to socialism and liberalism within its own time and absorbing its tensions

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on February 1, 2026

After the publication of Rerum Novarum, the economic, political, and social practices of Catholics experienced a colorful and lively civil spring. Workers' associations, mutual aid societies, and Catholic trade unions multiplied, and cooperatives and rural credit unions exploded in particular. The effects of the encyclical exceeded expectations, because reality is always greater than the idea of reality, and imposes itself with its indomitable freedom. On the intellectual front, Catholic economists and sociologists gave rise to a new and intense season of studies, newspapers, and cultural institutions. Their forefather in Italy was Giuseppe Toniolo, the most influential economist in the Church after Rerum Novarum and the most important interpreter of Leo XIII's teachings. Toniolo made his best scientific contributions to economic history during the first part of his career (the 1880s). His work as a theoretical economist, on the other hand, was modest and not appreciated by the best economists - Pantaleoni wrote to Pareto in 1909: “In Pisa, economics is being murdered by the good Toniolo” (Letters).

His reading of history was perfectly consistent with that of Leo and with neo-Thomism. The breaking point and beginning of the Italian and European decline is identified in Humanism, which he reads as a pagan phenomenon and as the decline of Scholasticism. It was in the fifteenth century that the great mistake was made, when “the transition from the Christian Middle Ages to the modern age, from the social order matured by the Church to the human social order of pure reason” (1893) took place. With Humanism, the goal “is man, where utility inevitably prevails, ready to degenerate into selfishness.” The growth of man was interpreted as the decline of God (and vice versa), as if the human-divine game were a zero-sum game (-1/+1), a thesis that we unfortunately find in much Catholic thought of the Counter-Reformation.

This created a natural convergence between Toniolo, the historian of the Florentine economy, centered around the ‘arts and crafts guilds’, and Leo XIII, who pointed to those medieval institutions as the solution to the socialist class struggle and the overcoming of liberal individualism. This restorative tendency in Toniolo's thinking was also noted by Alcide De Gasperi: “In the urgency to oppose the future socialist state with a Christian ideal, he perhaps exaggerated the importance of medieval municipal and corporate democracy: the bright aspects of an era, whose shadows had not been sufficiently highlighted” (1949). The search for a ‘third way’ was therefore the great project of Toniolo and his school, convinced that Christian social reconstruction would only succeed if Catholics took care to ‘combat, on the one hand, the individualistic and liberalist economy and, on the other, the pantheistic economy or state socialism’ (1886). It is not surprising, then, that Father Agostino Gemelli, founder of the Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, titled the first article of Vita e Pensiero ‘Medievalism’, an article that begins with these words: “Here is our program: we are Medievalists.” He continued: "Let me explain. We feel deeply distant from, indeed hostile to, so-called ‘modern culture’“ (1914).

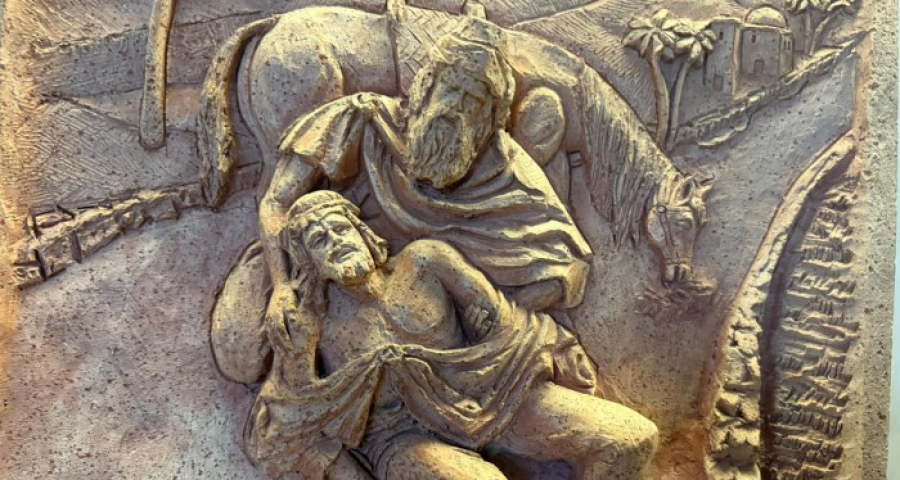

In 1903, Pius X ascended to the papal throne, followed by Benedict XV in 1914. Their major themes were the reaction to Modernism and the First World War (”the useless slaughter"). Pius X's fight against Modernism, defined as “the synthesis of all heresies” (Pascendi Dominici Gregis, 1907), is a perfect expression of the anti-modern line begun by his predecessors in the 19th century. Pius X devoted many of his resources to this struggle, creating a new inquisition structure to stem the epidemic, the Sodalitium Pianum, a secret network of inspectors to identify and report theologians suspected of Modernism. It was Pius XI, however, who explicitly continued the doctrine on social issues. The occasion was provided by the anniversary of Rerum Novarum, the Quadragesimo Anno (1931), an encyclical which, as Father Gemelli pointed out, “is not only the most solemn exaltation and the most authoritative commentary on Rerum Novarum, but also, above all, a systematic development” (1931). Pius XI defined Rerum Novarum as the ‘magna carta’ (QA §39) of the social order, because it had shown the working masses a new path “without asking for help from either liberalism or socialism, the former having proved completely incapable of providing a legitimate solution to the social question, the latter proposing a remedy that was far worse than the evil itself and would have exposed human society to even greater dangers” (§10). Pius XI thus reaffirms the social vision of the Church as a third way that seeks to “diligently avoid striking a double rock” (§46), navigating between Scylla (liberalism) and Charybdis (socialism): “Incidit in Scyllam cupiens vitare Charybdim” (Liberatore, 1889). The important ‘principle of subsidiarity’ already present in Rerum Novarum is re-proposed and developed. Above all, however, Pius XI reintroduces (§ 85, 86, 88...) the Corporations of Arts and Crafts, the Leonine solution to the socialist class conflict and capitalism: “He wanted the first place among these institutions to be given to corporations that embrace either workers alone or workers and employers together” (§29).

In the meantime, however, something extremely important had happened. Among the ‘new things’ was Fascism in Italy, and in 1927, with the ‘Carta del Lavoro’ (Charter of Labor), the corporative reform of the state came into force. Thus, ‘corporative social economy’ had become ‘a fundamental aspect of the political doctrine renewed and reconstituted by Fascism’ (Gino Arias, p. 5). Corporatism was based on the Aristotelian-Thomist tradition: ‘The organic doctrine of society, conceived as a real unity, distinct from the individuals and smaller groups that are part of it, is Aristotelian,’ writes economist Gino Arias. And therefore, ‘the superiority of the public good over the private good, concepts widely developed in the political doctrine of St. Thomas’. Corporatism thus presented itself as a true “third way” between socialism and capitalism: “The corporative economy is the negation of the hedonistic premise common to both liberalism and socialism” (G. Arias, Economia corporativa). These premises and promises were very similar to those of the young Social Doctrine of the Church.

In 1929, the Lateran Pacts were signed. Pius XI therefore wanted to add a few paragraphs to the Encyclical on the Italian situation, i.e., on fascism and its corporatism. Here they are: “Recently, as everyone knows, a special trade union and corporative organization was initiated” (§92). Then: “A little reflection is enough to see the advantages of the system as briefly indicated: peaceful collaboration between classes, repression of socialist organizations and attempts” (§96). Finally, medieval nostalgia: “There was a time when a social order existed which, although not entirely perfect and irreproachable in every respect, nevertheless conformed in some way to right reason, according to the conditions and needs of the times. Now that order has long since disappeared” (§98), and therefore... satisfaction with its reconstitution.

These texts are still embarrassing. Quadragesimo Anno ended up encouraging, or at least not discouraging, the adherence of many, too many Catholic economists to fascist corporatist doctrine. Among them was Francesco Vito, an important young economist at the Catholic University of Milan: “The corporatist economy is a new spiritual orientation for individuals” (1934). Father Gemelli's words were even clearer: "Since 1893, three events have taken place in the social sphere: the promulgation of Rerum Novarum, that of Quadragesimo Anno, and today the agenda of the head of government's speech. Three related events. The first marks the Christian condemnation of liberal disorganization; the second marked the reaffirmation of that condemnation and its extension to the latest socialist formulations; the third sets out principles according to which a modern state, Italy, overcomes liberalism and socialism and completes its corporative organization" (1933). Vitale Viglietti, in his essay Corporativism and Christianity (1935), stated that “such a conception, that of fascist corporatism, is identified with the social idea of Christianity. This is a statement that should be a source of great satisfaction for all Italians.”

Finally—but we could continue with dozens of other similar quotes—Father Angelo Brucculeri, a Jesuit and important writer for Civiltà Cattolica on economic and social ethics issues, wrote: “Today, corporatism in its various forms is a great fact that fills and characterizes our historical moment... But it is not enough to have established the corporation; it is also necessary to develop and multiply corporative consciousness not only among the elite but also among the masses” (1934).

Thanks to this cultural affinity, fascist corporatism met with little resistance in Catholic and pontifical universities. Almost all of the professors who adhered to the corporative economy later had the opportunity and time to dissociate themselves from fascism, and some of them became protagonists of democracy, the Constitution, and reconstruction. But that first season of the Church's social doctrine, too preoccupied with fighting socialism and moderating capitalism, ended up resembling corporate economics too closely. The first landing place of the humanism advocated by Rerum Novarum was a mistaken third way. In order to avoid Scylla and Charybdis, Peter's boat collided with an even more monstrous rock.