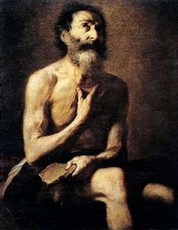

A Man Named Job/14 - In the sky of faith even the clouds help us sense God

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 14/06/2015

Sergio Quinzio, Un commento alla Bibbia (A Commentary on the Bible).

The happiness and pain of a civilization depends very much on its idea of God. This applies to those who believe but also for those who do not, because every generation has its own atheism deeply attached to his dominant ideology. Believing in a God who is like the best part of the human is a great act of love for those who do not believe in God. Good and honest faith is a public good, because being atheists or non-believers in a god made trivial by our ideologies makes everyone less human.

In the development of his poem in the Book of Job, Elihu deepens the discussion on the saving value of suffering. And even though it is following a theological line that does not convince neither Job, nor us, it suggests some new questions: "If there be for him an angel, a mediator, one of the thousand, to declare to man what is right for him, and he is merciful to him, and says, ‘Deliver him from going down into the pit; I have found a ransom; let his flesh become fresh with youth; let him return to the days of his youthful vigour'"(33,23-25).

Biblical monotheism is far from simple and straightforward. Along with the great words on the uniqueness of the God of the Sinai, an antidote for the eternal temptation of idolatry, if we dig into the scriptures we find a living and fruitful layer that delivers to us a God with a plurality of faces. Job, too, in the most dramatic moments of his trial, invoked a God other than the one that the faith of his time communicated and that he had known in his youth. Job continuously and tenaciously searches for a God beyond God, a 'Goel', the guarantor who can guarantee and defend his innocence and recognize his righteousness against the God who was killing him unjustly.

Here Elihu also shows us, among the thousand angels of God, a 'rescuer angel' that, moved to mercy by the pain of man can intervene with its merciful hand freeing him from the abyss where he was plunged by the other hand of God. This variety of hands and faces of the only Elohim (whichis the plural of Elohah in Hebrew, and El in the ancient language) is beautiful and rich. Christian tradition has in a sense saved it by defining a Triune God, recognizing that YHWH is unique but not a sole being, though in Christian doctrine the dark face of YHWH that was still present in the Gospels (where a God-father abandoned a God-son on the cross) disappeared all too soon. A single, full deity who is only light cannot understand the questions of Job nor the despair of the other victims of the earth. If faiths today want to prepare a home for the men and women of our times who think the sky is empty above them, they must recover the shadow inside the light of God, by inhabiting and crossing it with the many Jobs that populate the world (there are countless Jobs around our religions). Job will not hear God speak from the thunder today be if we eliminate the clouds from the skies of faiths.

Elihu keeps mentioning God's justice, and he defends it against Job. He too feels the urgent need to perform the job of the defence lawyer of God, a profession of which there has always been a very generous offer in all religions, in the face of a modest of non-existing demand: "Of a truth, God will not do wickedly, and the Almighty will not pervert justice" (34,12). However, Job had denied the justice of Elohim, and he did not start from theological theorems but from his own particular status as a victim. In his cause to God, he first of all tried to defend his innocence, showing that it does not deserve all the pain that others interpreted as divine punishment.

Job could have won his case in the divine tribunal by denying that God was the reason of his illness, and so saving it from having to answer the injustice of the world. But he did not, and he continued to believe in a God who is responsible for evil and innocent suffering. At this point, helped by Elihu, we must ask ourselves: why would Job not free God from the evil of the world? In Job's culture joys, sorrows and misfortunes were the direct expressions of the divine in the world. In his and his friends' world whatever happens is intentionally wanted by God, and if unjust things happen (misfortune of the honest and happiness of the evil), it is God who wants or at least allows for it. Retributive theology - in almost all ancient religions - was the simplest type of mechanism, but it was also very powerful and reassuring to explain the presence of God in history: positive events in our lives are the prize for our righteousness, and negative ones are the punishment for our sins (or for those of our fathers). "And Elihu answered and said: '...What advantage have I? How am I better off than if I had sinned?’” (35,1-3). In principle, Job could have found a first way to save his own and God's righteousness, too: he should have simply denied retributive theology altogether. But, in his universe, the high price of this denial would have been the recognition of an injustice on earth against which even God would have had to admit his impotence. In that culture, this would have been an impossible price to pay.

The ethical operation performed by Job had a revolutionary effect and it consisted in proving the innocence of the victim of evil, a revolution the deeper meaning of which we modern readers have lost (our beliefs and our non-faiths are too different and distant). At this point of his book, however, we must also recognize something that could surprise us: not even Job freed himself completely from retributive theology, because in his culture that liberation would have simply meant atheism, or making religion irrelevant. Job, in fact, by accusing God of injustice against him and against the victims, continues to save the cultural framework of the retributive or economic vision of religion and life. And in this context of retributive faith, not even he (which is what attempted to really undermine this religious theory) can detect a twofold innocence: that of the misfortunate righteous and that of God. Therefore Job preferred to sue God rather than lose faith in the God whom he was suing.

Only the discovery of a fragile God could have saved his innocence together with his faith in an innocent God. Only a God who also becomes a victim of the evil in the world could assert his justice and that of the righteous poor. Perhaps it is in this waiting for a different Elohim running through the entire book and persisting even after the response of God, that we can find Job's demand for a still unknown God who is able to accept his own impotence in the face of the evil in the world. Along with his innocence he would have to admit a weak God, too, an Almighty who is helpless in the face of evil and pain.

But Elihu indicates a second way to Job: the indifference of God: “Look at the heavens, and see; and behold the clouds, which are higher than you. If you have sinned, what do you accomplish against him? And if your transgressions are multiplied, what do you do to him? If you are righteous, what do you give to him? Or what does he receive from your hand?” (35,5-7). The God of the Bible, however, is not indifferent to human actions: he is moved, he repents, he rejoices and he gets angry. So Elihu cannot be right, because YHWH-Elohim has been known as a God interested in what happens under his sky. And Job knew this, he knows it now and will always know it. If we had to deny any contact between our actions and God's 'heart' in order to save him from the evil in the world that he created, we would lose the entire biblical message. Job did not give up in his fight so as to save a God who has a heart of flesh. To save himself, he was not satisfied with a useless God or one that is only useful for theological disquisitions that almost always end up by condemning the poor. If the actions of man are useless to God it is God himself who becomes useless for man - do not forget that Elihu's reasoning is in the centre of the project of modernity. Job, we have seen it many times, waits for and calls for a God that looks like the better part of humanity and exceeds it, too. We can suffer for the injustice and wickedness of others, and we rejoice in the love and the beauty around us, even when we suffer no harm or have any advantage personally. This human compassion is the first place where we can discover God's compassion. Anthropology is the first test of any theology that does not want to be idolatry-ideology. If God does not want to be an non-movable motor or an idol, he has to suffer for the evil we have done, he should rejoice in our justice, must die with us on our crosses. If we are capable of doing it - how many fathers and mothers are nailed onto the crosses of their children?! - then God should be capable of doing it, too.

Retributive logic has not disappeared from the earth. We find it strong and in a central position in the 'religion' of our global capitalism. Its new name is meritocracy, but its effects and function are the same as those of the ancient economic theologies: find an abstract (never concrete) mechanism that is able to both ensure the logical order of the system and reassure the conscience of his 'theologians'. So, in front of the rejected ones and the victims of the market, the 'moral' circuit closes recognizing the lack of merit in the losers, the 'non-smart', who find themselves more and more rejected and blamed for their misfortune.

At the end of Elihu's monologue the Book of Job provides no answer to either Job or his friends. Job continues to remain silent and to call for another God. A God whom neither Elihu, nor Job, nor the author of the drama know yet - and we neither. But will this new God come? And why is he so late to come, while the poor continue to die innocent?

Download pdf