A Man Named Job/6 To do justice means not to "cover" the suffering of the righteous

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 19/04/2015

Praised be You, my Lord, through our Sister Bodily Death"

(St. Francis, The Canticle of the Creatures)

Guilt and the debt are the big issues of life for everyone. In German they are almost the same word: schuld and schuldig. We are born innocent, and we can stay so for all our life. Just like Job. The death of any child is innocent death, but also many deaths of old people are just as innocent. And God, unlike the idols, must be the first to "raise his hand" in our defence, to believe in our innocence despite all the accusations of our friends, religions and theologies. The prisons are still full of slaves accused of nonexistent debts, and the jailers who get rich by trading with their innocent victims for panting liberations.

After the first round of dialogues between Job and his three "friends", we now enter a new act of the book, when each friend takes the floor again to repeat, with more emphasis, their respective criticisms, accusations, theories and sermons. And Job, in the centre of the scene, sitting on the pile of manure, continues to pose the biggest questions, awaiting different answers. His patience is not exercised towards God (with whom he is radically impatient) but towards his "friends". Having received the responses of Job, also Eliphaz, the friend who had taken the first word (ch. 4), becomes aggressive and attacks: “Should a wise man answer with windy knowledge, and fill his belly with the east wind? Should he argue in unprofitable talk, or in words with which he can do no good?” (15,1-3). His accusation is explicit: “But you are doing away with the fear of God” (15,4). And he adds, “What is man, that he can be pure? Or he who is born of a woman, that he can be righteous?” (15,14) Job responds: “I have heard many such things; miserable comforters are you all. Shall windy words have an end?” (16,1). And he reaffirms his indictment: "I was at ease, and he broke me apart; he seized me by the neck and dashed me to pieces” (16,12).

In this new variant of the dominant theme of the desperate song of Job - I am innocent, it is God who has to explain what he is doing to me and to all those unjustly suffering on earth - there are some precious pearls embedded.

Job, who is not content with and exasperated by the trivial answers obtained from friends so far, given God's silence, continues to call for an arbiter and neutral judge who can prove his innocence and then enact the just ruling: “Even now, behold, my witness is in heaven, and he who testifies for me is on high... that he would argue the case of a man with God, as a son of man does with his neighbour.” (16,19-21). And so, after a recourse to the language of procedural law, Job now passes on to the commercial register. He invokes the figure of the guarantor and asks God to give him a guarantee: “Lay down a pledge for me with you; who is there who will put up security for me?” (17,3) The guarantor was the one who guaranteed a debtor in front of his creditor with his own reputation or heritage, joining in his responsibilities in the event of default - an institution similar to our surety. Together with the debtor, the guarantor got also involved, providing guarantee for him by a lifting up of hands (manum levare: lift up one’s hands, is where "mallevare", the Italian word for guarantor comes from). This is why Job's prayer is very powerful and tremendous - the Book of Job offers many different and beautiful prayers, especially for those who have exhausted their own prayers and seek other, truer ones. Exhausted by pain, by the non-answers, the academic discourse of his friends, Job raises a new cry to God: be my guarantor, lift up your hand for me! But how is it possible that God, the creditor, may also be the guarantor for the debtor (Job)?

Here we find another beautiful passage. Albeit through misted eyes, he had gained a different view, and so Job tries to glimpse inside the God of everyone to see a more hidden God who is deeper and truer than the one he had known as a young man. There has to be a face of Elohim that is on the side of the unfairly oppressed poor, willing to raise his hand for them. Job is calling Elohim to become what he does not yet seem to be. If the God of the Bible is called just, good, slow to anger and merciful, then you should be able to turn to a face of God without denying the other. And look for a new face - “Your face, Lord, do I seek” (Psalm 27). Every prayer, if it is neither magic nor the result of fear of God or of living, is to call someone by name, asking them to become something that they are not yet - and the same is true for us. Job is accused of insolvency, and was put in the streets by non-existent debts charged to him. In the ancient world (and today, still) you were made a slave for unpaid debts, and not rarely you died in prison. From the bottom of his prison, Job turns to heaven: You know - at least a piece of you should know - that the accusation that led me here is not true, that my debts are just false accusations. I shall prove it, in fact you will tell the real reasons of my misfortune to everyone; but now, in the abandonment, I pray you: be my guarantor. Lift your hand up for me. At least you - the different face of the one God - give me confidence!

It is a strong demand with extreme confidence that is a claim made by many righteous people every day. The world, inside and outside prisons, is full of innocent people who keep repeating Job's prayer: if I am righteous - and I know I am, and I will not cease to believe I am innocent because I am - there must be, on earth or in heaven, someone who will believe me, someone who will give me credit! Too many times there is no guarantor for the righteous victims, they just cannot be found, or do not respond to the call. Job cries out and continues to do so - also for those who could not find a guarantor for themselves. In this miserable state as he finds himself at the bottom of the pit of extreme humiliation, Job hears inside that ancient voice again: “although there is no violence in my hands, and my prayer is pure” (16,17). If Job had given in to the demands of friends and pleaded guilty, he would not have given God the chance to become the last guarantor for the poor and the victims of all times. The faith of Job in a different and more humane God forced God, through all the books of the Bible and throughout history, to demonstrate this different and new face of his. Therefore Job is not only widening the horizon of the human who is good and a friend of God: he has also widened the horizon of God towards men. If it is true that man has learned to become more of a man through the relationship with the God of the Bible, it is also true - paradoxically - that the God of the Bible has "learned" to live up to his promises more through the relationship with men. The God of the philosophers has nothing to learn from history, and is almost always useless for the lives of the poor. The God of the Bible is a different God. Let's ask Job, or Mary who saw a child become a man, be crucified and resurrected.

But the pearls of these chapters are not finished there. While invoking that extreme type of guarantee, Job feels his death very close already: “My face is red with weeping, and on my eyelids is deep darkness” (16,16). A new prayer blooms from his soul, which is among the most beautiful ones in the whole of the Scriptures. A phrase, a ray of light enclosed in one verse: “The rabbi who taught me Hebrew could not read this verse for the thrill he felt over it” (Guido Ceronetti, The Book of Job). Some verses of the Bible can be understood only by not being able to pronounce them for the pain felt over them: “O earth, cover not my blood, and let my cry find no resting place” (16,18).

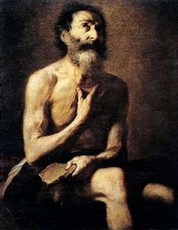

The moment Job feels his certain defeat and death, he lowers his eyes, looks on the ground and calls her by name. Crushed and smashed, he learns to pray the earth. This prayer - which is the opposite of the off-season mother goddess cults - is the song of the earthling, of the Adam who was dropped with his nose in the dust and can speak to the earth (adamah), to see and feel her differently, as a loyal friend. And he calls the pit his father and the worms his sisters who shall eat his body, inhabitants, like him, of the same earth. We need stigmata to be able to actually call the earth and death our sisters.

The earth heard Job's prayer. It did not cover the blood of many righteous people, and it continues to keep the memory of the cry of Job and his brothers. Every person, every community and every culture has its places that continue the cry of Job and the innocent. Memorial columns, monuments, the son's old room, a lot of poetry and art that conserve the cries of the soul - even if too much of spiritual blood is shed, covered and absorbed by the earth, for lack of poets and artists, or because it is too secret and big to be seen by someone. These places know them and recognize them, and we thank the earth and its inhabitants for not having covered them, for allowing the cry-song of Job not to go out inside the throat of the world. The earth has to be asked and begged not cover the blood of the righteous, because life would and should cover it. Human love asks the earth to forget, burying the great pain - but Job unearths it for a truer type of love.

The earth did not absorb the blood of Abel, when his brother "raised his hand" not to protect but to kill, and the smell of that righteous man reached up to God (Genesis, chapter 4). Job, another righteous man, asks the earth not to absorb his blood, because he wants its smell to reaches all the way down to us. His living cry asks us to become guarantors who are responsible and in solidarity with the many innocent victims. Will we lift up our hands to save them?

Download pdf