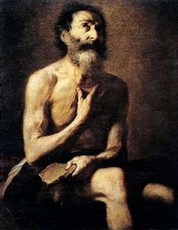

A Man Named Job/1 - Moving beyond the “retributive” vision of faith

by Luigino Bruni

published in pdf Avvenire (65 KB) on 15/03/2015

Raymond Carver, Cathedral

The world is populated by a countless number of Jobs. However, very few of them have the gift of crossing through their misfortunes in the company of the Book of Job. The reading and meditation of this masterpiece of all literatures is also a spiritual and ethical company for those who find themselves going through the experience of Job: a righteous person, honest and upright, who at the height of his happiness is struck by a great misfortune, without any explanation.

Even the righteous can fall into disgrace. But today, just as in the days of Job, friends, wisdom, philosophy and theology seek explanations for misfortunes, and even today it is very hard for us to think that a man or a woman could tumble down without any blame. Just as a gift needs a good reason to be explained and understood, so does the disaster that strikes humans: we need to find a reason to satisfy our thirst for balance and our sense of justice. Our common sense cannot live together with misfortunes for which there are no reasons. The Book of Job, this monument of ethics and universal religion, tells us that doom and righteousness can coexist, and that even those who are righteous and good can fall into the biggest and deepest abyss. Therefore the misfortune of others does not say anything about their righteousness, just as it says nothing about their wealth. And in a time that is making merit the new cult, Job reminds us that real life is much more complex and alive than our meritocracy is. Today, more than ever before, there are rich people without any merit and with many demerits, as well as impoverished people who have fallen into misfortune, even though they are good.

But if misfortune strikes both the just and the unjust, both the good and the bad, then the great temptation is to think that the world is ruled by chance, by luck and to deny that it is worth cultivating virtue, as luck will always win. God, Elohim, YHWH, the Lord of the Covenant, the good voice of the patriarchs, Moses and the other prophets, is it the same God of Job or is his another one? Or is there no God and so are we destined to be devoured by increasingly sophisticated and hungry idols? The book of Job is not only a great treatise of ethics showing the way of salvation in times of great trials; it is also a text that shows us a different face of the God of the Bible. The one that attacks Moses to kill him immediately after speaking to him at the Horeb (Exodus 4), the one who sends his angel to stop Balaam (Numbers 22), the opponent of Jacob-Israel in the night ford of the Jabbok River (Genesis 32). In order to go through the Book of Job, we have to face a fight during the night. It is a risky river ford, we can only say to have passed it at daybreak, when the night wrestler leaves a sign for us, teaching us a new dimension of life.

In every encounter with the texts of the Bible, if we hope to hear ourselves being called by name from a real voice one day, we have to read it as if for the first time, because it can only open up to us and surprise us this way. We have said this many times. To meet and love Job, this spiritual and moral exercise is indispensable and it is also a thoroughgoing one. We must lose sons, daughters, property, health, cursing life with him sitting on the pile of manure, and above all we must not be content with easy explanations to start blessing it again quickly. Because of this, reading the Book of Job is an arduous exercise and only a few can complete it. Job forces us to take the contradictions of life, the non-answers and the silences seriously, and to attempt something paradoxical: to include them all in the good Book of Life. If Job, his screams of pain and his curses are the word of God, then there are no human words that are naturally excluded from salvation. Job has extended the horizon of the human for us, as a friend of God and life, incorporating all of the kind of humanity that knows only the language of pain and despair, by telling us that even muted words can compose a true dialogue between heaven and earth, perhaps the most real one of all. “I no longer go to church, after my five-year-old granddaughter died. I'm too angry with God,” a friend of mine, a friend of Job told me one day.

Job is a book for adult life. To read it and love it one needs to have tasted disaster in one’s own life, or at least in that of a dearly loved person. Only those who can lean toward the mystery of life and look at it with absolute freedom can hope to penetrate something of the message of Job; but we need to dare to ask for the more difficult answers, even those that seem absurd and impossible. Without asking for the impossible, what is possible is never good or true.

The issue at the heart of the Prologue is gratuitousness. The first scene of the book shows us a happy man, Job. He is introduced to us with no mention of a father or mother, as a new Adam, a man. It is in the first words where the universal message of this book lies: “There was a man in the land of Uz whose name was Job” (1,1). The name of Job is of uncertain etymology, it is not a Hebrew name: Job is not a son of Israel; he is just a man, like Adam. Without father or mother. A resident of a foreign country, perhaps in the land of the Edomites, a foreign people, inimical and idolatrous. An “everyman”. But Job was also a “blameless and upright” man, like Noah. At the beginning of the drama, Job is a happy man: “There were born to him seven sons and three daughters. He possessed 7,000 sheep, 3,000 camels...” (1,2-3). He was also rich because of the happy relationship of his sons and daughters: “His sons used to go and hold a feast in the house of each one on his day, and they would send and invite their three sisters to eat and drink with them” (1,4). He was also a pious and devout man: “And when the days of the feast had run their course, Job would send and consecrate them...” (1,5). He was a “perfect” man, an accomplished and flourishing human being.

In the second scene we find ourselves in a heavenly location, where God and his “sons and daughters” are together. Among them there is Satan, too (who in the Book of Job is one of the members of the heavenly court, perhaps one of the sons of God). Satan has just returned from a trip to the earth, where he noticed the righteousness of Job. And this is where the central dialogue begins. Satan insinuates a doubt, presented to God as a thesis: “...Satan answered the Lord and said, »Does Job fear God for no reason? ... You have blessed the work of his hands, and his possessions have increased in the land. But stretch out your hand and touch all that he has, and he will curse you to your face«” (1,9-11).

The expression “fear God for no reason,” can also be interpreted “unrewarded”, “without being paid.” Because of this, at the heart of the story of Job there is also a religious and anthropological revolution that seeks to overcome the remunerative vision of faith (our wealth and our happiness is the prize for a faithful life, ours or that of our fathers), which has also been central in the ethics of capitalism.

The question on gratuitousness, however, is the centre of human existence. Are we capable of freeing ourselves from the register of reciprocity making up the grammar of our social and affective relationships, and act only out of pure love? Job will not give us easy answers to the question of gratuitousness which seems to be the origin of the bet between God and his angel Satan, and perhaps it is because it is greater than the greatness of Job.

Therefore, the story of Job is a teaching not only about the ethics of the misfortune of the righteous, it is also a radical reflection on the meaning of human existence, and so it's a great myth of initiation to life. The sons and daughters are not ours, we will leave this body of ours, and our pain and that of others is our daily bread, the land where we are born and live is not ours, the goods are not there forever. The enemies and natural disasters first kill his livestock (1,14-17), and finally the greatest tragedy hits: “While he was yet speaking, there came another and said, »Your sons and daughters were eating and drinking wine in their oldest brother's house, and behold, a great wind came across the wilderness and struck the four corners of the house, and it fell upon the young people, and they are dead...«” (1,18-19). Job then “arose and tore his robe and shaved his head and fell on the ground and worshiped. And he said, »Naked I came from my mother's womb, and naked shall I return. The Lord gave, and the Lord has taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.«” (1,20-21). It is from this nakedness that his dialogue begins, his struggle starts in search of blessing after receiving those big wounds. To learn, with no easy consolations, the craft of living, Job should be a decisive, perhaps necessary encounter for us. His closest friends are Ecclesiastes, Leopardi, and some great pages by Dostoevsky, Kafka, Nietzsche and Kierkegaard. If a religious sense-making is possible, it should listen very carefully to the questions of Job, and at least try to come up with some answers. If we follow Job deeply, without anything taken for granted, and until the end, we can have an experience that is similar to what Raymond Carver tells us in his wonderful story entitled “Cathedral”. In it, a blind man takes the hand of his host, who could see with the eyes of the body but had never seen, or had forgotten to have seen, a cathedral, and hand in hand they manage to draw it together. Let us join hands with Job, and together we will be able to draw a masterpiece.

Download pdf