A Man Named Job/15 - The soul is alive as long as we seek Him who has not answered to us yet

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 21/06/2015

(Elie Wiesel, Biblical characters through the Midrash).

When, having waited and hoped for it for a long time, the decisive encounter arrives, it usually lets us down. That imagined and hoped-for meeting was too great to be satisfied by a real encounter. We had dreamed of it and 'seen' it a thousand times in our soul. We had already pronounced the first words in our thoughts and chosen the dress for the other, glimpsed him/her, felt his/her smells and heard the sounds he/she makes.

But there are no real words, clothes, smells, colours or sounds that would equal to those imagined and printed in our longing hearts. Even faith, all faiths feed on scraps between these dreamful meetings and the encounters that actually occur, and surprise or even disappointment, is the first experience of every authentic spiritual life, the first sign that the God were waiting for was neither an idol nor just a dream. Because if those who actually come are too similar to those we have dreamed of, it is certain that we won't be changed through that encounter. The soul is alive and does not go out as long as we keep longing for that different God who did not attend the appointment.

And so, after a wearying wait, we are about to see the appearance of the most important witness in the courtroom, the one that Job relied on relentlessly. The Book of Job is great also because it was able to hold back and keep itself and us in God's silence for thirty-seven chapters. By not entering the scene, Elohim allowed us to push our questions to the very end, and Job to finish his poem. Too many times our songs do not become God's masterpieces because God's lawyers make them come to the scene too soon. The truest presence of Elohim in the drama of Job was his absence, his most beautiful words were the ones unsaid when his friends asked him to speak and to make his powerful voice heard. A silent but real sky is more capable of saving us than a sky filled with words that are not enough human to be true.

God starts speaking from the midst of a storm but does not answer the questions of Job, he does not descend to the level we expect. Why? No theology can give an abstract answer to the most radical questions rising from the innocent who are suffering in the world. People are capable of asking more questions to God than the answers he can give us because a God who has ready and perfect answers for all our great and desperate why-s is only an ideology or, in the worst but very common case, an idol that we have built in our own image and likeness. The God of the Bible learns from our big and desperate questions and he is surprised when we put them to him for the first time. If it weren't so, creation, history, ourselves and time would all be but fiction, and we'd all be inside a TV set with God as the only, bored spectator. Only the idols do not learn anything from people, because they died without ever having been alive. The gap between our questions and the answers of God are a space for the true experience of faith, and when theologies seek to reduce or delete these differences they do nothing but alienate their man and their God from the Bible.

“Then the Lord answered Job out of the whirlwind and said: “Who is this that darkens counsel by words without knowledge? Dress for action like a man; I will question you, and you make it known to me. “Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know! Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone, when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?” (38,1-7)

Elohim does not accept the dialogue between equals that Job asked of him, and he does not respond to his questions. He scolds him and reminds him of the infinite abyss separating the Creator from the creature - a gulf that Job knew, but that did not prevent him to sue God. He does not call Job by name but as 'faultfinder' and 'he who argues with God' (40,2). The Book of Job and perhaps no holy book knows a God who is able to fight on par with Job. Only an extreme type of God could stay close to the extreme humanity of Job. The God of the book, in fact, can only make Job quiet, to bring him back in the coordinates of a creature, but in doing so he also leads himself back inside the theological barriers from which Job had tried to untangle him throughout his many lines. Job had asked for a greater God than the one he had known; but, at the end of his poem, he finds the same Elohim of his youth, as if the drama of Job had not taught anything to heaven. Perhaps we could not ask any more of the book. But we can and must ask Elohim for more, we must ask him to be different from how he is presented by this great biblical book, which is perhaps the greatest of all. Along with Job, we must continue to pose questions that are bigger than the answers we get, not being content with a God who is too much like the one we knew and that theology told about to us: the one who is the creator, omnipotent, wise and wonderful. All this we had already known before we got to know Job. Now, having listened to and cried with him facing the pain of the innocent in history, the God-before-Job is not enough for us. It is not what Elohim says in itself that is disappointing (if you extrapolate it from this book we find a lot of poetry and beauty in it): it is what God says at the end of Job's cry that leaves us unsatisfied. Is it possible that only we have changed, and that Elohim has stayed the same as he was in the bet with Satan that we saw in the prologue of the book (chaps. 1-2)? But then does the innocent suffering of the world not reveal something new about the universe even to God? And if it is so, then what good is it for us to remain faithful and honest to the end in endless solitude?

Therefore we have a spiritual and ethical duty to ask for more, to continue to implore God to tell us something he has not yet said to us. Because if we do not do so, we lose contact with the poor and with the victims, with those who continue to cry out and with those who are too helpless at the spectacle of evil to be consoled by the omnipotence of God. The poor and the victims do not ever keep silent in the name of God, even when they curse against the sky. When you look at the world together with the victims, when you attend the existential, social, economic and moral suburbs of the world, the greatness and power of God seem too distant, and, above all, it does not push us to do everything possible to reduce suffering in the world with our freedom. No narration of the incredible things of the universe, no magnificent description of the terrible Behemoth ("He makes his tail stiff like a cedar; the sinews of his thighs are knit together. His bones are tubes of bronze, his limbs like bars of iron." 40,17-18), or the Leviathan ("His back is made of rows of shields, shut up closely as with a seal. One is so near to another that no air can come between them..." 41,15-16) can comfort and love those who scream as they are sinking into the sea, or those who die alone in the beds of elegant hospitals. Only the God awaited by Job could meet them and collect their screams. But that God is not to be found in the Book of Job: “Or who shut in the sea with doors when it burst out from the womb, when I made clouds its garment and thick darkness its swaddling band, and prescribed limits for it and set bars and doors, and said, ‘Thus far shall you come, and no farther, and here shall your proud waves be stayed’?” (38,8-11).

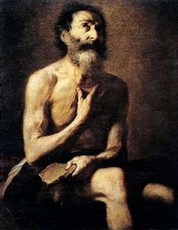

To the ear and heart of Job, sitting lonely on the dunghill, at the ford of his desperation, these words that are perfect in themselves would only have produced the same effects as the wise words of his 'friends': they only increased his loneliness and abandonment. In fact, even this God wants the conversion of Job and asks him to surrender - which he will get: "And the Lord said to Job:

‘Shall a faultfinder contend with the Almighty? He who argues with God, let him answer it.’ Then Job answered the Lord and said: ‘Behold, I am of small account; what shall I answer you? I lay my hand on my mouth. I have spoken once, and I will not answer; twice, but I will proceed no further’” (40,3-5). Job, as so many innocent victims, is made quiet, he is silenced. This Elohim, the defence attorney of his own unfathomable omnipotence, is not the God that the poor and the innocent like Job seek and deserve.

The responses of this God cannot match the questions of Job. His words are not up to the moral height of the words of Job. But - and this is where the extraordinary mystery of the Bible lies - Job's words, too, are God's words, because they are embedded inside the same and only scripture. Therefore we can listen to the voice of God by making Job speak who denounces and attacks him. By defining the whole Book of Job (and other books) 'sacred', biblical tradition has created a wonderful and eternal alliance between the words of YHWH-Elohim and those of man. The word of God in the Book of Job and in all the scriptures is to be found also in the pages where Job speaks and shouts; where men speak, in their extreme, unanswered questions. We can pray to God with the words of Job without God. This mestizo God who wanted to mix his words with our own is the only one capable of speaking from the burning bushes of the earth, and still calling us from there by name.

Download pdf