The sign and the flesh/1 – We now begin the commentary on the Book of Hosea, the first of the so-called Minor Prophets

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 28/11/2021

«When I began my commentary on the book of Hosea, now seven years ago, I was convinced that I knew it well enough. Today I think that the richness of this prophetic book is still largely unknown»

Joachim Jeremias, Hosea

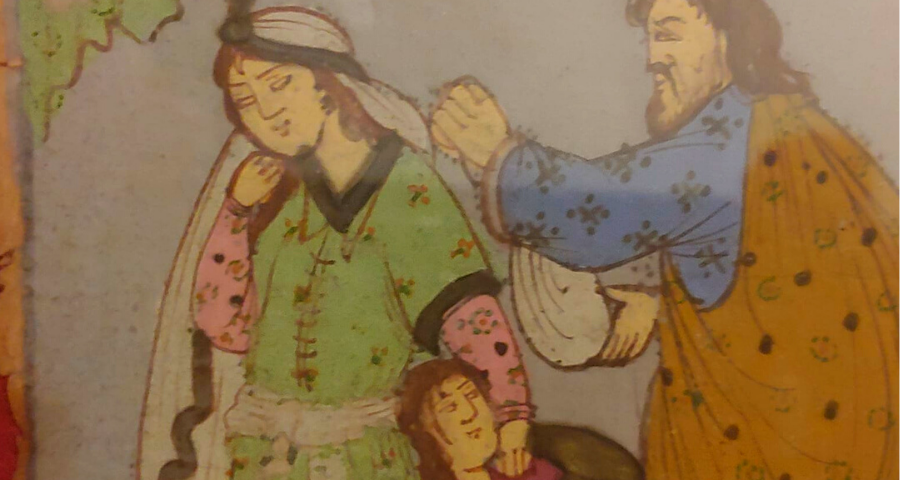

Hosea, husband of Gomer, engraved his vocation into his own flesh, a vocation that was revealed early on in a paradoxical start. And it will help us to understand the different type of craft that prophecy is.

The Bible speaks a lot about faith. It speaks less of trust, which is the other twin meaning of the ancient Latin word fides. It speaks little of it because trust is a necessary condition of the Bible, its unspoken, fundamental hypothesis with which to start any profitable biblical reading. Because the Bible opens and reveals itself if we trust it, if we give credit to it, if we believe it. Before believing the words contained in the Bible, it is necessary to believe the Bible, because the truths of the Bible are beggars of our trust in the Bible. Here lies the typical weakness of the biblical God: he cannot communicate anything to us unless we first trust his word.

If we truly believe that it is not lying to us, and if we believe the words of the characters in it, if and as long as we do not have strong and convincing reasons to doubt it. In short, if we believe in the words of all of its protagonists, but above all in those of the prophets, which are the quotation marks of God. Then, when we read the first line in the Book of Hosea: «The word of the Lord that came to Hosea son of Beeri during the reigns of Uzziah, Jotham, Ahaz and Hezekiah, kings of Judah, and during the reign of Jeroboam son of Jehoash, king of Israel» (Hosea 1,1), we are thus invited to believe that what that ancient prophet, with the wonderful name ("YHWH saves", similar to Isaiah), is telling us is above all a historical fact. Hosea was indeed a prophet; he truly began his prophetic activity in the Northern kingdom during the reign of Jeroboam II.

Hosea is the only writer-prophet from the Northern Kingdom where he lived and prophesied. He was a little younger than Amos, a little older than Isaiah. He operated during the last tumultuous years in the existence of the Northern Kingdom, between 755 and 724 BC approximately. Hosea therefore spoke and wrote when his land was going through a profound crisis, which would later culminate - he was still alive - with the first deportation to Mesopotamia. He was therefore a first row spectator of a political and religious decline. Hosea is an important prophet, perhaps essential, for communities or people who are experiencing a decline, crises, or who are heading towards deportation.

Here then, we already have the revelation as to why we should return to the biblical prophets, and to Hosea in particular, today. Biblical prophecy is a precious and often unique map for orienting oneself well on dangerous foggy excursions, on steep off-trail descents because the path does not exist or has not yet been traced. In the difficult and risky passages of a community, it is with the prophets that we must confront ourselves daily and tenaciously, to be taught by them.

The Book of Hosea is the first book by the so-called twelve "minor" prophets, although it does not appear to be the oldest (perhaps it comes after Amos). It is the first because Hosea creates the theological framework in which the other eleven books should be read. Hosea's themes, biography and metaphors influenced Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and perhaps even Isaiah, and therefore the entire Bible, the Old and the New Testament.

«When the Lord began to speak through Hosea» (Hosea 1,2). This beginning of verse 2 is important because it inserts Hosea’s paradoxical and sad family events within the dialogue between God and Hosea, and includes his own biography among the words that Hosea transmits on God's command The historicity of Hosea's family events have always been discussed, and we will probably continue to discuss and bring new hypotheses into the discussion, in part because there are not enough elements in the texts to arrive at a single interpretation. Hence, once again, it is best to believe what Hosea told us and his disciples passed on to us. And then insert these first words of the book among those that YHWH addressed to Hosea: «The Lord said to him, “Go, marry a promiscuous woman and have children with her, for like an adulterous wife this land is guilty of unfaithfulness to the Lord"» (Hosea 1,2).

If the words of the prophets are not fables, if they are not myths, (not only in the sense of Homer's tales, but also not in the sense of the mythical tales of the first chapters of Genesis), then Hosea’s words are also history, although history in a prophetic form, and therefore a message and sign that remain history. Because if the emphasis on metaphor and symbol ends up absorbing and cancelling the historical dimension of the words of the Book (as it often does), the heart of biblical humanism and prophecy will be lost, and reading the Bible becomes uninteresting.

We must not reduce the power of Hosea's word by transforming and transfiguring his biography merely into an allegory and metaphor of Israel's infidelity. Its story does, of course, also include an allegorical message for Israel and for the prostitution of politics, of the priests and of the powerful and mighty of its time and of all times and ages, but there is also the personal story of Hosea, his wife, his children, his life. Partly, because if we want to take the ancient meaning of the word-symbol seriously, we need to go back to the objects (coins or a piece of cloth) that were usually broken into two parts when making a pact. Each party took one with him so that when recognition was required in the future, they would each be able to combine their own part with that of the other party – among other things, telling us that every act of recognition requires at least two parties to come together. Hence, biblical symbols carry the message of God, his piece of cloth, but this piece would be rendered useless, if the other part is missing, the one made of the flesh and blood of men and women. Without the truth of our piece of cloth, biblical messages become mere vanitas and smoke, and above all, they can no longer save anyone or anything. This is also the difference between novels and biblical stories: a novel lacks the part of the flesh, and great novels are the ones that, in some way, have managed to give flesh and blood to their protagonists - and thus come very close to the Bible, until touching and intersecting it.

If we then compare Hosea’s story with the other great biographical stories of the prophets (Isaiah, Ezekiel, Jeremiah) we immediately realize that in his book, Hosea’s family story takes the place usually occupied by the day they received their vocation in the stories of the other prophets. In the Book of Hosea his vocation takes on the words of his wife and children. And that is how his vocation should be taken, without taking anything away from it, with not even one iota of controversy or paradox. Because God almost always speaks in the Bible within a paradox. Abraham believes in the promise of a new land and dies in a foreign land; Ezekiel receives the task of prophesying from God and immediately afterwards the same God makes his tongue stick to the back of his palate; and the Son of man, who came to announce the faithful love of God, who then dies on the cross crying out God's abandonment.

The story of Hosea is another episode in this paradoxical story, in the tale between us and YHWH, made up of absurd pains and surprising salvations. Thus, in order not to risk missing the most beautiful and revealing part of the book of Hosea, we need to believe that Hosea, as his first prophetic assignment, truly received the task to marry an unfaithful and adulterous woman ("prostitute" in this case, should not be understood in the sense of the mercenary profession, because the Hebrew word for that would have been different, zònà). To their disciples and to the people the biography of the prophets was too precious to be upset and desecrated, even if for theological reasons - the disciples and friends of the prophets are also the custodians of their biography, protecting them from ideological manipulation. This is why we must take this familiar information as something very serious indeed. In part, because it is part of the prophetic logic: Jeremiah received the order to remain celibate from God, and God took Ezekiel’s wife, the "light of his eyes", from him.

Hosea does not speak, he does not engage in dialogue with God, and he does not protest. He speaks through his actions, like Noah: «So he married Gomer daughter of Diblaim, and she conceived and bore him a son» (Hosea 1,3). When God and his prophets have a dialogue, they speak above all using their feet and hands.

The embodied symbol of Hosea, similar but even more paradoxical than the symbols of the other great prophets, reveals something decisive in the logic of prophetic vocation, of the Bible and of life, to us.

The prophet is the one who gives the flesh with which God writes his messages to humanity, which thanks to him / her become embodied messages (Judges 19,29). Long before speaking with his mouth, the prophet speaks with and through his whole body, through his life, through his biography, through his family and through his children. Here, we have yet another element telling us that happiness is never promised to the prophets in the Bible: in these stories, there is a person called upon to become a living message, nothing could be more distant from happiness. Back in the day as well as today, because if the search for one's happiness is never enough in life, in the Bible it is nothing.

Hosea then explains the intimacy of a prophet to us. It is both sign and flesh, together. He speaks using words, but sooner or later - at the beginning, in the middle or at the end of his life - the day will arrives when he becomes the very message he is announcing. He does not want it: it just happens to him. This is why receiving a prophetic vocation in times of a great crisis is a dramatic and heartbreaking experience. Day after day, the prophets take the form of their message, and if the message is harsh, severe, paradoxical, then the prophets become harsh, severe and paradoxical. They do not want it: they simply become it. It is not a good job, but it is their job, often useful, sometimes essential.

This is perhaps the reason why only the prophets can teach us the meaning of the word destiny: we are all greater than our destiny; we can change it and twist it with our freedom. The prophets, however, do not: they have many gifts, some great privileges, but they cannot change the essence of their destiny. And if they do, they lose themselves. Furthermore, with their absolute radicalism, they remind us all of something universal: if we have listened to a voice and announced the beauty of chosen poverty, the day will arrive when we become truly poor, and that message will become our flesh. If we sincerely have wished to give our life for an ideal, one day we will really give our life for it, even if it should be our very last day. Because it is not just prophecy, but also life, that is both sign and flesh, together.

Without prophets and artists (who are very much alike, perhaps too much so), social life would be just a matter of emotions, incentives and interests. A prophecy turns it into something different, something greater, and something unpredictable. Tragic and paradoxical. This is how it continues to enchant us, and we are grateful to it.