Commentaries – How wounds and crises become blessings

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 27/03/2016

Resurrection is a great word on earth. Life reborn from death is the first law of nature, that of plants and flowers that fill the world with colour and beauty, because they tell us that life is greater than death that feeds it. Women and men are reborn many times throughout their existence, finding themselves resurrected after grief, abandonment, depression or diseases that had crucified them before. Sometimes we rise again by resurrecting someone else from their tomb, and those have surely been the most beautiful and true resurrections we have witnessed. If resurrection had not been a human word, a friend and something familiar, those women and men of Galilee would not have been able to perceive anything of the unique mystery that had been completed between the cross and the day after the Sabbath.

Resurrection is a great word on earth. Life reborn from death is the first law of nature, that of plants and flowers that fill the world with colour and beauty, because they tell us that life is greater than death that feeds it. Women and men are reborn many times throughout their existence, finding themselves resurrected after grief, abandonment, depression or diseases that had crucified them before. Sometimes we rise again by resurrecting someone else from their tomb, and those have surely been the most beautiful and true resurrections we have witnessed. If resurrection had not been a human word, a friend and something familiar, those women and men of Galilee would not have been able to perceive anything of the unique mystery that had been completed between the cross and the day after the Sabbath.

If resurrection is a human word, then it is also a word of economics. There is much resurrection in the economy, in business, in the world of work. We can see it every morning, even in these times of crisis, and especially in these times of crisis.

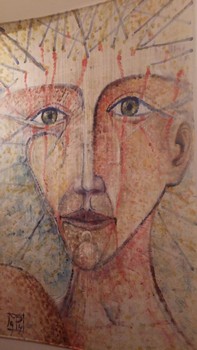

But we must learn to see it and recognize it, looking at the world with "eyes of resurrection." It is not easy to see and recognize the risen ones or resurrections for many reasons, but mainly because the bodies of the resurrected are bearers of the stigmata of passion. And our wounds and those of others make us afraid, so we flee from them and we cannot experience them as the beginning of resurrection and the sacrament that always accompanies it. And as we are looking for resurrection in the absence of wounds and pain, we do not find it, or maybe confuse it with success. We do not see resurrection because we think it's the anti-cross or the opposite of passion, and not its fulfilment. We flee from those crucified and abandoned, and do not encounter the resurrected that can only be found there. Resurrection begins on the cross, and its signs are forever.

The Risen Christ is the resurrection of his wounded body. The novelty of this resurrection is found in its corporeality, too. The resurrected body, however, is not a return to the body of Thursday (the day before the Passion); resurrection is not an event that erases the signs of the lashing and the Way of the Cross. The Christ appears with his wounds, the light of resurrection did not eliminate the stigmata of Good Friday. The glory of the risen one is therefore not the glory of the ancient hero: his is a wounded glory which is humble and weak. Risen ones appearing without wounds are ghosts, illusions, dreams or ideologies, and so their light is fake. Our resurrections start while the abandoned on the crosses are crying out. And if we do not learn to cry out, we shall not learn to rise again either. We shall not understand the logic of the beatitudes if we do not look at them from the perspective of someone resurrected with the stigmata.

The wounds that remain after the resurrection are fundamental to understand the economics of salvation, but also the salvation of the economy. If the wounds remain on the resurrected bodies, then there is an economics of the crucified and an economics of the risen. The cross and resurrection are in the same economy, in the same life. Therefore, to find the instances of true resurrections in our society and economy, we should go and look where no one is looking any more. We should start searching among the many companies that are being set up by immigrants and their wounds, the many cooperatives that flourish inside prisons, among those young people who decide not to leave their country and land, and humbly learn the ancient skills of the hands, or in the midst of those workers who do not capitulate in the face of the many reasons for property and the market but resurrect their company. Without making the mistake of thinking that the wounds that generated the resurrection will disappear one day, and there will be only light, everywhere.

When we hide the marks of our wounds, our resurrection stories - even the authentic ones - do not become credible places of hope for those who are still in the phase of the cross. In our economy there are too many disheartened people waiting to put their hands into the wounds of the resurrections, to be able to understand and love their own, not yet resurrected wounds in a different way. Resurrections are not found where wounds terminate, but inside them.

Among the many meanings of the word pèsach (Passover), the first Easter, there is also the verb limp (psh). When the reader of the Bible reads "limp" they think of Jacob, the great limper. At the nightly ford of the Jabbok River, Elohim wounded him in the sciatic nerve, made him lame and changed his name to Israel. According to the rabbinical tradition, Jacob limped for the rest of his life. In another night fight, at the ford of the Red Sea the new people was reborn, but the sign-memory of the slavery in Egypt has never disappeared from its body. From the great battles of the Golgotha a resurrected body with the stigmata flourished. Resurrections are wounds turned into blessings, never deleted. When we rise again, our wounds remain, but become luminous. True resurrections can be recognized by the light that radiates from their wounds.

Editor's note - The image of the "Risen Christ" by Michel Pochet (CentroMaria) is located at the Mariapolis Faro (Križevci, Croatia)

Download pdf article in pdf (93 KB)