The idea that trade is more profitable than war, as Montesquieu said, falls short in the face of evidence, confirmed by economist Antonio Genovesi, that financial interests are one of the main causes of conflict.

by Luigino Bruni

published in Città Nuova on 18/10/2025

In one of the most famous books in European political history, Montesquieu's The Spirit of Laws, we read: “The natural effect of trade is to bring about peace” (1748). A few years later, in his commentary on Montesquieu's book, the Neapolitan economist and philosopher Antonio Genovesi wrote the opposite: "Trade is a great source of war. It is jealous, and jealousy arms men" (1768). Montesquieu's thesis is the one that has most inspired and influenced modern hopes and illusions. We saw the development of trade, we also saw wars, but we hoped that wars would end on the day when trade reached all peoples, who would finally understand that trading was preferable to fighting.

The whole of modern political economy was built on this idea and this hope, theorizing and showing that trade is much more beneficial to everyone than war. These hopes grew considerably after World War II, when we began to think that the market economy was definitively defeating war, and that the “regional” conflicts that still existed and arose here and there were only feudal remnants that would soon be absorbed by the great tide of economic and civil progress. Perhaps in the second half of the 20th century there was no social utopia more popular than this.

In 1977, the great German economist A.O. Hirschman wrote another small but highly influential book, entitled The Passions and the Interests, in which he took up Montesquieu's thesis (and that of other Enlightenment thinkers, including G.B. Vico) and developed it into a full-fledged theory. The pre-modern world, theancien régime, was characterized by passions—pride, honor, revenge...—which were very dangerous because they were unpredictable and irrational, not following the logic of rational calculation. And so, the people and peoples of yesterday destroyed and self-destructed, dominated by revenge or honor. If someone offended you, and given the infinite value of dishonor, you challenged them to a duel because either by winning you restored your honor, or death was better than a life of dishonor. With the advent of the market and trade, Hirschman continued, we moved from passions to interests, where the latter are based on rationality and calculation, and therefore actions become predictable and, above all, less dangerous and destructive than passions. Hence his reinforcement of Montesquieu's prophecy, the prediction of a future with more peace, serenity, and less conflict, thanks to the market. With these high hopes, we first encountered the war of 2022 in Ukraine, then in Gaza, and finally Trump's statements on tariffs.

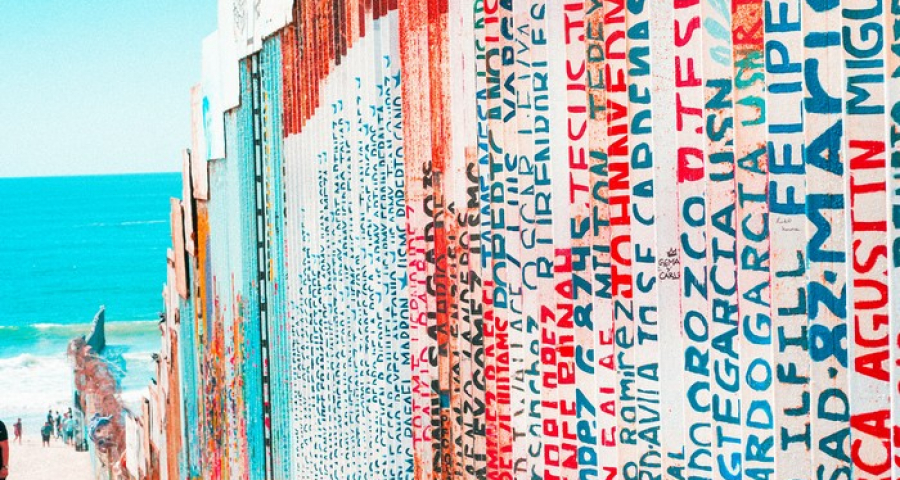

And I thought back to Genovesi, to his thesis on trade as a ‘great source of wars’, which he had arrived at at the end of his life as the culmination of his reflection on the market and the civil economy. Genovesi was convinced that exchange, trade, and the market remained something very important for individuals and peoples, because he saw them as a form of civil reciprocity (“mutual assistance”); but he also knew that the powerful and the strong often use trade, especially international trade, as a means of increasing wealth and power. He said this clearly and with sadness because he too hoped that Montesquieu's prophecy would come true. He also knew, like all economists, that the archaic mercantilist logic of tariffs is only a dangerous illusion, because tariffs harm everyone, in primis those who impose them, because they quickly lead to a decrease in wealth for all parties involved – technically, it is a “prisoner's dilemma.” Putin, Trump, and many other politicians who emulate them tell us, unfortunately, that Montesquieu and Hirschman had dismissed passions from the repertoire of economics and politics too soon. The 21st century, in fact, is returning to being the century of destructive passions, populism, honor, patriotism, the idolatry of borders, leaderocracy instead of democracy, and the denial of science and therefore of rationality. The market economy has a vital need for rationality: rationality alone is not enough, humanity and pietas are also needed, but rationality is essential. It is likely that, if we do not put an end to this political season soon, democracy and the markets will be the great victims of this wave of passion. Young people are reacting all over the world: let us stand by them, support them, and learn from their different intelligence.

Photo credit: © Barbara Zandoval on Unsplash