The Dawn of Midnight/2 - Beyond the sea of slavery, where the idols die

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 30/04/2017

"When he brought the ready drink to Jeremiah's bedside, he was breathing quietly in his sleep. "Since I cannot hide it from the world, how can I hide it from you?" ..."Hide what?" (...). "The Lord was with me... And his voice spoke to me. And his voice is sending me away from here." Abi's eyes filled with tears. She did not cry because the Lord had come to him. Shouldn't she be proud of all the women of Jacob? And yet Abi's heart broke with sorrow for the election of her son."

"When he brought the ready drink to Jeremiah's bedside, he was breathing quietly in his sleep. "Since I cannot hide it from the world, how can I hide it from you?" ..."Hide what?" (...). "The Lord was with me... And his voice spoke to me. And his voice is sending me away from here." Abi's eyes filled with tears. She did not cry because the Lord had come to him. Shouldn't she be proud of all the women of Jacob? And yet Abi's heart broke with sorrow for the election of her son."

Franz Werfel, Hearken Unto the Voice

There is a conflict, a radical tension, between the prophets and power. For many reasons, but above all because the prophet, by his task and vocation, can see the natural tendency of every power - above all the one dressed in a sacred mantle - getting distorted and turning into tyranny.

He can see it, he tells it to us, he shouts it out. He knows that the powerful are inconvertible, that the only positive action against them is denunciation, criticism, the unveiling of their real intentions beyond their beautiful and adulating words. Power is the hobby horse of prophecy: it "loves" criticizing it hard, screaming at its natural corruption, not converting to its reasons, staying motionless in its seesaw. The "good" kings and the "good" leaders are those who know how to stand under the blows of the ruthless critique of the prophets and do not try to buy them to convert them to their reasons. When prophets disappear or become false prophets, the corrupt nature of power becomes perfect, governments transform into empires, and we into slaves.

"The word of the Lord came to me, saying, »Go and proclaim in the hearing of Jerusalem, Thus says the Lord, / ‘I remember the devotion of your youth, / your love as a bride, / how you followed me in the wilderness, / in a land not sown’«” (Jeremiah 2:1-2).

Jeremiah, who grew up listening to the stories of the Northern tribes, is deeply connected to the tradition of the Covenant; the memory of the days of the first love is very much alive in him: "Israel was holy to the Lord, / the firstfruits of his harvest" (2:3). It is because of that first Covenant, that first and always valid wedding pact (Hoseah) that YHWH had given to his people a land, liberated them and led them out of Egypt: " (he) led us in the wilderness, / in a land of deserts and pits, / in a land of drought and deep darkness, / in a land that none passes through" (2:6). Jeremiah cries out against the leaders of his people because Israel has unilaterally broken the pact: "What wrong did your fathers find in me / that they went far from me (...)?" (2:5)

It's a total betrayal, general unfaithfulness: "The priests did not say, »Where is the Lord?«/ Those who handle the law did not know me; / the shepherds transgressed against me; / the prophets prophesied by Baal / and went after things that do not profit." (2:8) The rebellion involved the three axes on which the life of the people rested. It's important to note the reference made to the corruption of the prophets who have shifted on to the service of the god Baal, an element that reveals another dimension of prophetic function to us. Prophecy is not exclusive to Israel, and prophets can recognize the same breath in other peoples, they know how to recognize each other. The sin committed by the prophets denounced by Jeremiah was that they became prophets of Baal. They are prophets who have changed gods.

There is, perhaps, no greater spiritual perversion than that of the prophet who begins to prophesy in the name of another god. You can stop being prophets for many reasons - few prophets remain true prophets for all of their lives. Because sometimes the prophetic task is temporary and it takes time for the task to be performed; because they stop hearing the voice, and so they have nothing to say anymore (sometimes the voice really disappears, sometimes it is the prophet who loses the ability to hear it); or because the prophet cannot withstand the pain that his vocation gives him, and chooses to retire to private life. These endings of prophetic stories are possible, very common, and sometimes even good. The life of prophets who trade gods is, however, always bad. That's because prophetic vocation is the encounter between two personal voices: one that calls by name and the other that answers to the name and the call. The not-false prophet knows and recognizes that unique voice, he knows how to distinguish between the many voices of life. When - for money, for power, for pleasure, for perversion ... - he begins to speak in the name of another god, he automatically becomes a false prophet because he does not speak in the name of any voice. Prophets are inconvertible to other gods because they are essentially-ontologically linked to their first personal voice, one word, one language of the spirit.

The impossibility of changing the prophetic voice is universal, and even when the prophet does not call the voice that inhabits him "God", or, as Etty Hillesum who calls her simply and magnificently, "the deepest part of me". It is true in art, poetry, but also for those who follow the great human ideals. The poet knows that his vocation is tied to a single specific voice that has called him and calls him every day. And he knows that if he loses his relationship with that voice he loses his vocation and gets lost. Nevertheless, he sometimes decides to prophesy for other "gods" (almost always money and power). He knows he is becoming a useless prophet of nothing, but he still goes ahead: "I have loved foreigners, / and after them I will go." (2:5) These phenomena are also found in community experiences when vocations get grouped around collective charismas, where in times of very strong crises there is a temptation to begin to prophesy in the name of other "gods" and to fill their temples with other similar deities - and so get lost and lose one's soul. These losses are unavoidable in the historical arc of the development of a charismatic community, which can save itself if at least one prophet remains faithful and does not stop crying out the words suggested by the real voice to him. They are inevitable because there always comes a moment when their "god", if it's a true god, seems too difficult, different or more inconvenient than that of the neighbouring peoples. As for Israel, idolatry has always come as a response to the people's demand to finally have a god like everyone else: visible, pronounceable, touchable, simple: "(they) say to a tree, »You are my father,« / and to a stone, »You gave me birth«" (2:27).

This is the root of every idolatrous conversion: the inability to remain in a spiritual state that is imperfect and not fully satisfying, and thus transforming God into a consumer good that fully responds to our religious preferences. When God or an ideal ends up coinciding with our idea of God or the ideal, we are already in idolatrous worship: the truth of every faith lies in the gap between our tastes and our experience, which is the space where we can hear the subtle voice of the silence of truth.

The true prophet who becomes false because he changes "voices" is far more dangerous than the false prophet who is such from the beginning, and the unhappiness of the previous type is also much greater. The nostalgia for the first good voice never leaves him, and accompanies him faithfully, as a thorn in the flesh, throughout his mercenary peregrinations: "Yes, on every high hill / and under every green tree / you bowed down like a whore" (2:20). You can return to the first voice, but these moments of return are very rare.

Furthermore, Jeremiah is very lucid and determined in identifying the reason for unfaithfulness: the people have betrayed their wedding covenant: "(they) went after worthlessness, and became worthless" (2:5).

The name that the prophet gives the idols is strong and significant: worthlessness (or nothingness - the tr.), wind, breath, smoke. He uses the same word that has become famous thanks to Qoheleth: hevel (vanity). The worthlessness of the idols, however, is radically different from the sense Qoheleth gave to it. Qoheleth's vanitas emerges from the background of a world emptied from the idols, from a space freed from the vanitas of illusion. It is a liberating and true nothingness that tells about the frailty and the ephemeral nature of the human condition. It is nothingness that's full, just as the songs of Leopardi or some bright pages of Nietzsche are true, full and liberating, where nothing appears beyond the "twilight of the idols," like the epiphany of an absent truth in the illusory vanitas of man-made totems.

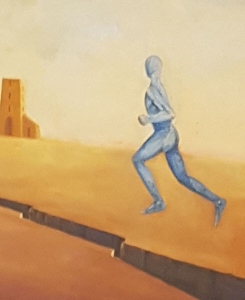

Much of the spiritual path of an entire existence consists in getting rid of the wrong kind of nothingness that seemed true to approach another, radically different nothing. Sometimes this second nothing is the dawn of a new journey in search of a new truth; at other times, the second nothing remains until the end: it expands, deepens, grows with us, and allows us to generate good and tasty fruits, which are very similar, if not identical, to those found at the end of the third journey. There are many men and women who for decades are nurtured by this second nothing which is true, accepted, embraced, and beloved as the good human condition beyond the consolatory illusion of the first nothing. The third journey doesn't start without having been liberated from the first nothing and having landed on the truth of the second nothing: the phase of the second nothing is inevitable. Many spiritual and therefore human paths get stuck in the first illusory nothingness for the fear of facing the second nothing with its desert landscape and arid climate, and so they remain servants and slaves of nothingness: "Is Israel a slave? Is he a homeborn servant?" (2,14).

There are very many false prophets of the first nothing on this earth. There are also, though very rarely, prophets of the third journey. But beside them and their great friends one can recognize the prophets of the second nothing, who, in their empty desert, are inhabited and nurtured only by the voice - and they have no need.

The second nothing is still not the promised land, but it is already a land beyond the sea of slavery, which sometimes extends to the slopes of Mount Nebo, where we can fall asleep with Moses, seeing Canaan on the horizon.

download pdf article in pdf (100 KB)