Roots of the future/4 - Sometimes you meet a second Good Samaritan. And it becomes decisive

By Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 24/09/2022

The meeting between Jean Valjean and Petit-Gervais in "Les Misérables" is a reflection on how resurrections take place in life and the role that children play in this. Sometimes what feels like a relapse into your old life is just the first step into a new one.

For true and lasting conversions, understanding only with your mind is not enough: rationality and intelligence are too fragile. Such events depend very little on our intentions. They just happen.

There was a long period of time during which children and young people did not grow up inside their homes. Misery generated many little vagabonds. Some fled from orphanages, others without a family wandered in search of seasonal jobs, some created small street shows to scrape together some money. All exposed to the violence, both by permanent residents and travellers. In the nineteenth century, you could still find many of them in Europe. Too many can still be found today in cities all around the world. In Brazil, they call them meninos de rua, in other countries they have no name, they live in the streets, without a home and without a family, exposed in the squares and spaces of deprivation.

Jean Valjean ran into one of these vagrant boys. Petit-Gervais would turn into his second Good Samaritan. He had just been "redeemed" by Bishop Myriel, who in response to his theft of silverware had given him a second extraordinary gift of candlesticks and freedom. Now he is wandering in the fields, confused and prey to a thousand thoughts: «He felt a kind of anger; he did not know against whom» (Les Misérables, I, 13). Encountering Myriel's agape after twenty years of imprisonment was for him an event that was both wonderful and terrifying: «In coming out of that deformed and black thing called prison, the bishop had hurt his soul like a too bright light would have hurt his eyes when he came out of the darkness». That excessive gift from Myriel after his theft made Jean Valjean see how he had suffered a theft of his own existence with new clarity: «Like an owl that suddenly sees the sun rise, the convict was dazzled and as if blinded by virtue». Thus, «he contemplated his life and it seemed horrible to him».

Anyone who has been reached by a great and gratuitous source of love while in a condition of error and sin knows that the encounter with that agape light hurts the soul: «It seemed to him that he was seeing Satan under the light of heaven». We see more, we understand more, and we suffer more: the light makes us see our darkness in all its tremendous grandeur, this new vision of the past frightens us, and that fear can turn into anguish. This is why sometimes, many times, the encounter with an authentic form of gratuitous love is not enough to truly start a new life: that great light is not able to free us from our past, which, paradoxically, weighs upon us even more because we can see all its gravity.

During this inner battle of light and darkness, Jean Valjean sits down behind a bush: «He turned his head and saw a small twelve-year-old Savoyard who singing coming along the path, with the hurdy-gurdy [a small string instrument] hanging on one side and his packing on his back. One of those docile and cheerful boys who go from one village to the next, with their knees showing through the holes in their trousers». The boy did not know he was being watched as he was playing tossing his few coins up in the air and catching them on the back of his hand. Suddenly, a forty sous coin escapes him and «rolled towards the bush, up to Jean Valjean. Jean Valjean put his foot on it». The little one approaches him: «Sir - said the little Savoyard with the confidence that comes from being a child, that mixture of blissful ignorance and innocence - my money!» Jean Valjean asks him for his name: «Petit-Gervais, Sir». «Go away - said Jean Valjean». «My coin - cried the boy - my silver coin! My money! ... The boy was crying». At a certain point, «Hey, are you still here?, said Valjean, abruptly getting up on his feet, and with his shoe still resting on the silver coin, he added: Are you going to leave or not?». At that point, «the boy looked up at him frightened, he began to tremble from head to foot and after a few seconds of stunned silence, he fled, running with all his might».

Jean Valjean was still sitting down. It was getting dark. When bending down to pick up his stick all of a sudden he saw the money: «What is this»? «He began to look far ahead in the distance... and he began to shout with all his strength: Gervasino, Gervasino». By then the boy was far away, but Jean Valjean continued to shout: «Petit-Gervais, Petit-Gervais». He met a priest and asked him about the boy, but to no avail. He continued running, searching desperately for the boy: «Petit-Gervais, Petit-Gervais, Petit-Gervais, he shouted one last time». Then he fell to the ground, exhausted, and «with his head between his knees he cried out: What a wretch I am!» His heart burst: «It was the first time that he cried in nineteen years».

A second, powerful light had reached him, a different kind of light. This time it did not arrive from the bishop's agape, but from the «blissful ignorance and innocence» of a street urchin. The violation of that ignorant innocence now carried on the resurrection initiated by the gift from Myriel. That boy’s name - Petit-Gervais - repeated obsessively, over and over again, shouted, and cried out with desperation, is about to roll away the stone from the tomb.

For true and lasting conversions, understanding merely with your head is not enough: rationality and intelligence are much too fragile. Those few, very few events that really change us - sometimes just the one - are not the fruit of our will; they depend very little on our own intentions. They just happen: they await us behind a bush as we wander around in confusion without really looking for anything. Jean Valjean was already part of a process of conversion; his resurrection had already begun in Myriel's home. In order to conclude it, however, there was also a need for an encounter with the violated innocence of an innocent. If an adult had dropped that silver coin, the effect would not have been the same. Children have and safeguard a mystery of absolute gratuitousness and innocence. When an adult steals a penny from a boy, the theft is of a different nature: it is the theft of life. It is our condition as adults that teaches us to distinguish people from their things (without ever quite succeeding). The beautiful things that belong to children, on the other hand, are closely connected with their bodily being and flesh. This is why their things, or goods, even the few coins they possess, are never those of an adult: the matter (the res) is the same, but when things arrive in the hands of a child the "substance" of that matter changes even if the "incidents" do not. The hands of children operate "transubstantiations that are different but no less real than those performed by the hands of a priest. Violating their belongings is sacrilege. In the oikonomia of life, the value of coins handled by children is different, their path is different - they roll away differently. Thus, reminding us that coins, all coins, get their true value from the relationships in which they are used, abused, donated or stolen. Back in the day as well as today, in literature as in life.

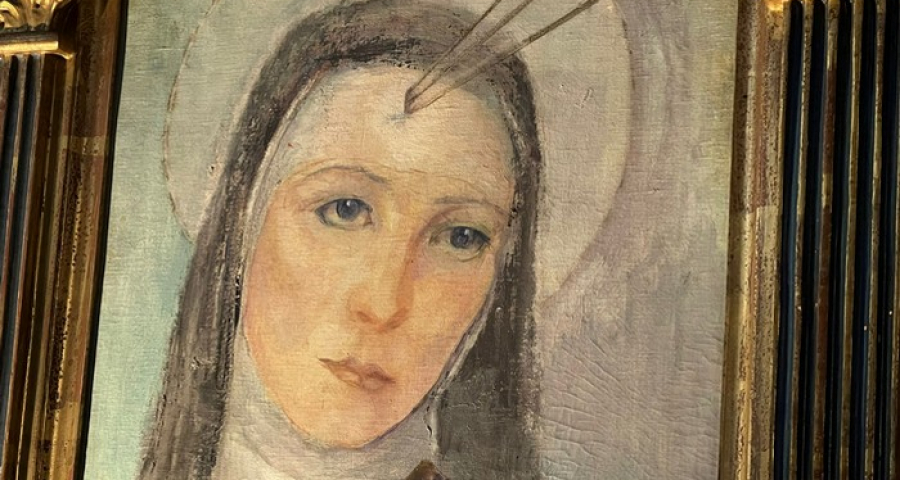

Thanks to an authentic act of grace – Victor Hugo was really creating a treatise on the theology embodied in grace for us - Jean Valjean suddenly becomes aware of having committed a sacrilegious act, of having violated a sacred place, of having profaned a host. Because every child's heart is a tabernacle - every person's heart is. He could not have understood this sacrilege without first having experienced the bishop's gift of agape, but that extraordinary gift would not have generated its fruits of life, without the subsequent profanation of the mystery of that child’s coin. Jean Valjean's heart was able to feel horror and anguish over that stolen coin because he had already been touched and wounded by Myriel's gift. The experience of being loved with true agape-love begins with a cut in the soul that creates a crack where a new source of pain can enter, which we could not know about beforehand because our hearts were too hard. When resurrection begins, love and pain coexist, and being able to experience a new quality of moral pain is the first sign that the heart has really changed.

And within this very acute pain, Hugo makes Jean Valjean say one of his most beautiful phrases: «A voice whispered in his ear that he had crossed the solemn hour of his destiny, that there was no more middle ground for him, that if by now he did not become the best of men he would become the worst». We are presented with choices whose outcome will make us a little better or a little worse during the most ordinary days of our lives. There are a few days that are different, however. The days of great judgment regarding our life, and we are the judges. During one of these days, you choose between heaven and hell: purgatory is no more. When we feel with infinite clarity, that either we try to become the best we can be or we will most certainly become the worst of men on earth. It was the day of Father Kolbe, the day of Christ on Golgotha, of Francis in front of his father and of the bishop of Assisi; it is also the day of so many of us, ordinary men and women, who, however, sometimes end up having an extraordinary day. The true meaning of the word "salvation" and of that other symmetrical expression, "getting lost", is closely connected to these kind of days. You can make a mistake and go on living an erroneous life because we are not able to see the evil we are doing: but if one day, by an act of grace, we finally see that evil and we do not choose not to do it again, yesterday's evil will become tomorrow's hell.

Hence, there is one last message in this non-meeting between the ex-convict and the little Savoyard, for us and for the people we love. When a person who has been deeply loved begins a new life, there is often a phase that goes from Myriel's door to Petit-Gervais’ bush. Having had received an authentic act of grace, we see the coin roll away again and we think that that first gift and that hope were wasted; they were only illusions. Hugo is telling us: watch out! Perhaps you are observing Jean Valjean somewhere along the path between the door of the curia and the bush. That act of wickedness that he should not commit and yet he does, can be the first step in a new life. He is already a new man although still clothed in the pain of the man he was before: «In stealing that money from that child he had done something of which he was no longer capable».

Too many times, we misunderstand the situation and proceed to condemn it, because we do not give Jean Valjean time to cry out in despair: «Petit-Gervais!» He is already on the right path, but to be able to continue on a good path he also needs our trust. Jean Valjean was saved by Myriel and he was saved by Petit-Gervais, by both of them: by the innocence of the virtue of an old man and by the natural innocence of a poor child. This great piece of literature makes us go through the experience all the way to the end and then repeats to us: "Go, and do the same yourself".

Finally, it is a powerful experience - for the boys and girls of Fridays for the Future and the Economy of Francesco of today - to see the eyes of Petit-Gervais asking us for his stolen money. When will we be able to hear his cry again? When will we lift our heavy foot from the coin on the ground? When will we give him his childhood coin back?

_large_large.png)