The Market and the Temple/11 - The weaving of relationships that Tuscan Francesco Datini made great is exemplary. Pessimism, cynicism, envy and distrust are the great capital sins of any business.

by Luigino Bruni

Published in Avvenire 17/01/2021

Virtuous and successful trade belongs to those who work both for money and by vocation. Both those two things together. Wealth, like happiness, comes while (also) seeking something more.

Those who observe economic life from afar often end up missing the best elements of this aspect of life. They see incentives, meetings, offices, algorithms, rationality, profits and debts. They hardly ever realize, however, that behind the strategies, contracts and business schemes there are people, and among them, there are some who really put all the meat on the fire, all their passion and intelligence; their life into those companies. From afar and from the outside, we see the traces of that work, but we rarely see the body of those who leave those traces, and we almost never see their soul. Nevertheless, when we are able to see the souls, in those same enterprises we discern both spirits and demons, angels rising and falling from heaven.

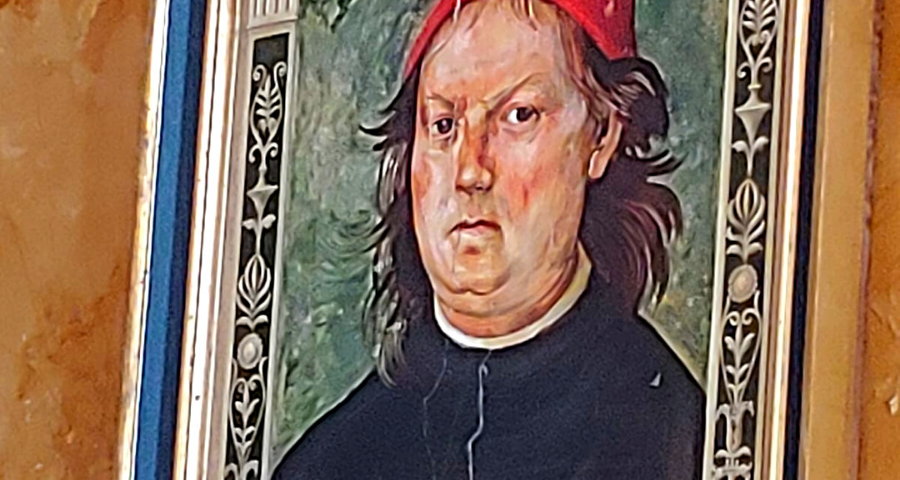

The letters, diaries and memoirs of Italian and European merchants of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries are precious sources because they let us enter the souls of the people inside the merchants in the auroral phase of this profession. The life and letters of Francesco di Marco Datini (1335-1410) feature some extraordinary and exciting elements. Francesco was the son of Marco (from Datino), a butcher from Prato who died, together with his wife and two of four children, during the plague of 1348. Francesco was raised by Piera, their neighbor – yes, the "dark" Middle Ages included things like this as well. After a short period working in Florence as an apprentice, at fifteen Francesco left for Avignon, where he first became a shop boy and then began his trade as a merchant. He founded a real multinational business, with companies in Prato, Avignon, Florence, Pisa, Barcelona and Valencia, boasting a patrimony of over 100 thousand florins by the end of his long life, which he left for charity. Europe was built above all by monks and merchants, spirit and commerce, who together ended up doing wonderful things.

In the thirty-two years he spent in Avignon, Datini therefore achieved a considerable wealth, so much so that when he returned to Prato he was called «Rich Francesco» (Paolo Nanni, Reasoning among merchants/Ragionare tra mercanti: for a reinterpretation of the personality of Francesco di Marco Datini). He gave life to an innovative business system, a real holding company. Each company had its own economic and legal autonomy, but the Florentine company "Francesco Datini and companions" held the majority shares of that complex corporate network, which unfolded in the main European town squares, centred on the production and trade of wool, silk and "anything one wished to trade". Such a mercantile network was based above all on an exceptionally complex and dense web of relationships. And it is in the art of trading understood as the art of relationships that Datini's true genius is revealed.

With him, the character of the merchant truly stands out, his habitus, very similar to the monk's habit, understood as an existential stance, a way of being in the world. Trading coincides with being a merchant, a profession with destiny. In one of his letters, Datini writes that if he were to continue to work only for the money it would not be worth it: «Our profession brings with it so many things that you end up paying more money than the castle is worth» (Datini, letter from 1378). In a letter from 1386, his young wife Margaret reproached him that the «good life» that he had promised her, never arrived: «You always preach that you will have a good life ... This has been said for ten years already and yet today I am less able to rest than ever: this is your fault». A merchant's activity ends up coinciding and merging with his life: «I am resolved to act as the medic who while he lives medicates» (1388).

Scrolling through his letters, preserved in the State Archives of Prato, one cannot help but to be struck by some of the aspects of that mercantile ethic. First of all, the relationship between the merchant and wealth. The virtues that he systematically teaches his associates are many and not all of us today would associate them with the trade of a merchant. He recommends risk («whoever would stop sowing for fear of flounder will never sow anything»), but at the same time he also recommends temperance («whoever hunts too many foxes ends up losing one while the other one gets away»). He praises speed and efficiency («he who does something quickly does it twice»), coupled with knowing how to be satisfied with what you have («better to have a pigeon in your hand than a thrush on a branch»). He encourages audacity («a man of arms will never suffer from a lack of horses»), but at the same time moderation («a wise merchant once said money will earn you ten per cent if you keep them in the trunk»).

A wisdom of commercial practice seasoned by ancient wisdom (Seneca, Cicero, the Bible), by popular proverbs, which together lead Datini to elaborate the golden rule of his business ethics: not to make the pursuit of wealth the only or the first goal of trading and the market. The exclusive desire to earn is a passion that can blind you. So much so that a wise merchant should occasionally look at himself with the eyes of an external and impartial observer; as in a game of chess, where a child who observes the players «sometimes sees more than they do, because the one who watches is not passionate about the fear of losing or of winning or gaining» (1402). For Datini, the great vice of a merchant, understood as a great mistake, is avarice, which also prevents him from really earning, since a wise merchant must be able to control his own greed for profit in order to be able to earn.

A business ethics that therefore refers directly to the ethics of virtues, (which Datini knew and taught). In that worldview, virtue is understood as an attitude to be cultivated to achieve excellence in a specific area of life. In order to be virtuous, behaviours cannot be solely and entirely instrumental, a certain amount of intrinsic value is also required: an action must also be practiced because it is good in itself and not only as a means to obtain something external to that action. An athlete will not be virtuous (excellent) if he competes only to win and not for the love of the sport itself, nor will a scientist who does research only for fame and not for the love of science as well. In trade, however, this external or instrumental dimension is particularly important. It is difficult to imagine that a merchant would operate only for the sake of trading and the relationships with his customers and suppliers, because obtaining a gain external to the action is part of the nature of trade itself. Datini, however, reminds us that without a dose of love for the market and its related profession and mission, a "merchant" will only become distorted (change his nature) and turn into something else – a usurer, for example.

A virtuous merchant is hence someone who works both for money and by vocation. Only a bad merchant works only for money (or works only by vocation, which can be even worse than the first case). Furthermore, those who only do it for money will not even really make any money, because it goes against the very nature of their profession. It is an ancient merchant law that those who are merchants do not get rich only to get rich. As if to say that, like happiness, wealth arrives while (also) looking for something else. So much so that at the end of his life Datini wrote that he had dedicated to trading «soul and body, not out of avarice or out of desire to earn, but only because I was let down [disappointed] by everything else» (1410).

When one continues the reading of Datini's letters, a second element or virtue of the "civil merchant" begins to emerge: a positive gaze on the world and above all on other human beings, who remained his existential and commercial beacon. In a letter from 1398, Datini tells us about the first reason that led him to enter into society with other companions at the time of Avignon: «The love I had for the people of the world». A splendid phrase that tells us the pre-requisite to profitably carry out the trade-vocation of a merchant. An entrepreneur who does not have any "love for the people of the world" will not become a good entrepreneur. Without looking at the world and people with a good and positive outlook, without seeing an opportunity to grow together in a new meeting, without trust as a starting point, one cannot practice the art of trading. The entrepreneur is, above all, someone who looks at the world as a set of relational opportunities, who believes that people are his first wealth and that the wealth of others constitutes a possibility for himself. Here lies his generativity, which always originates in the generosity of his gaze on other human beings. Pessimism, cynicism, envy and distrust are the great capital sins of any business.

As a consequence of this second "anthropological" virtue, a third virtue emerges from the letters as well, a virtue that was fundamental in the life and success of Datini: his great care for his relationships. Datini was a great weaver of relationships, of friendship and even of fraternity: «When I accompanied Chon Toro di Bertto to Vignone, many mocked me, saying: "You were free and yet you made yourself a servant". I replied that I was happy to have a companion for two reasons: one, to have a brother, next to me to fear in order to guard me from the indiscretions of youth». And then he adds: «How much safer and more delightful would it be to be two companions in traffic, who love each other as brothers?!» (1402). Despite the many disappointments that his business companions had caused him in the course of his commercial activity - «there is not one who has not cheated you at least 12 times a day», his wife Margherita reminded him in 1386, - he concluded with the wisdom of ancient proverbs: «He who has company is a lord». For this Prato merchant, having or forming a company is «the greatest kinship there is» (1397), which he compares to a family and the relationship between brothers. When a friendship ended, Datini invited his associates to exercise forgiveness: «With the exception of treason or theft or murder or filth or adultery that cannot be forgiven, for every other thing a man has to always try to return the love of a friend» (1397).

The cardinal virtue of an entrepreneur is the art of cooperating, and the art of cooperating cannot last without learning the essential art of forgiveness. Even if today's business schools, all taken with techniques and tools and bewitched by the wrong metaphors, (mostly military or sports related), have forgotten the strength of the gentle virtues, the truly essential ones in order to be able to do this difficult job. Entrepreneurs have always lived and continue to live on many and different forms of mutual benefit, they are the creators and consumers of company and friendship, both within and outside their companies. Hence, first of all, they should educate and form themselves in these very virtues, this is the character that they must cultivate. Practicing kindness, amiability, investing time, a lot of time, in listening to people, developing all those arts that facilitate the creation and maintenance of relational goods, which make up the first essential, invisible and very real asset of one's own company, on which its first beauty depends. Francesco di Marco Datini knew this exceptionally well, we must learn it again. We will get out of this crisis, and away from this pain plaguing the entrepreneurial world, by going back to "loving the people of the world".