Economic Soul/3 - The lesson of the magisterial document establishing the principle of subsidiarity: accept the challenges of your time without fearing it

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on January 25, 2026

Rerum Novarum (RN, 1891), the first encyclical entirely devoted to socio-economic issues, had a symbolic value far greater than its content. Its spirit was much more important than its letter. It stated that economic life and work were an integral part of the thinking and action of the Catholic Church: they were not on the periphery of evangelical humanism, they were at its center. Thousands upon thousands of Catholics finally felt seen, understood, and recognized by the Church in their civil and economic commitment. They already knew this, but after RN they knew it even more, and there were no more doubts. The historical judgment on the content of Rerum Novarum is, however, a different matter, requiring study and a certain amount of courage.

With the restoration of the ancient regime in Europe desired by the Congress of Vienna after the Napoleonic era (1814), the papacy had also hoped for a return to the world before the French Revolution, deluding itself that the Enlightenment, liberalism, and modern thought could be erased, thus returning to medieval Christianitas, feudalism, and the important political role that popes and bishops had played in past centuries. But the Church was mistaken. The European world had changed forever, and with it, the era of the Church's temporal power had come to an end, as had the era of the submission of states to religious authority. It was a long and painful process that the Catholic Church, the papacy in particular, experienced as a ‘cultural battle’ with modern Europe. At that stage, neither the liberal Catholicism of Alessandro Manzoni, nor the theology of Rosmini, nor the Christianity open to new ideas of the great bishop of Cremona, Geremia Bonomelli, prevailed in the Roman Church.

RN is a document that presents some lights, along with some shadows. The lights are real, important, and highly emphasized in Catholic social tradition. As the full title of the document itself says - De opificium conditione (on the condition of workers) - the condition of workers is a focus of the document. In fact, the most illuminating pages of the encyclical are devoted to work and wages, where the dignity of every worker is reaffirmed, a not too long working day is required (especially for children and women), and it is declared that the game of supply and demand cannot be the only criterion for setting wages: “The worker and the employer should therefore agree on the terms of the contract and the amount of the wage; however, there is always an element of natural justice that precedes and is superior to the free will of the contracting parties” (RN #34). The paragraphs of the Encyclical that establish what will later be called the principle of subsidiarity are also very important: “It is not right that the citizen and the family should be absorbed by the State: it is right, on the contrary, that both should be allowed as much independence as possible, without prejudice to the common good and the rights of others” (RN #28). Subsidiarity is expressed as the right of association, particularly of workers' associations (#37-39). Even the Church of Leo XIII could not renounce community and communities; it wanted to save the community dimension of the Church and with it the ecclesiastical, economic, and civil hierarchy.

The most obscure aspects of RN concern the theme of equality among men, and therefore his vision of wealth and poverty. To understand them, let us return to Matteo Liberatore's Principles of Political Economy (1889), published on the eve of Rerum Novarum. It deals with the great theme of private property and inequality, ideas that we find very similar in RN: “Two things, says St. Thomas, must be distinguished in property: possession and use. As for possession, it can be private, indeed it must be, for the sake of human life. But as for use, it must be common, inasmuch as the possessor shares with the needy what he has in excess” (Principles..., p. 342).

Leo XIII, already in his second encyclical, had affirmed very similar theses: “Socialists, Communists, and Nihilists ... never cease to babble that all men are by nature equal among themselves ... The Church, much more wisely and usefully, even in the possession of goods, recognizes inequality among men” (Quod Apostolici Muneris, 1878). From the defense of property, it is a short step to the defense of inequality (a thesis that we find in Liberatore's Principles of Political Economy (pp. 161-163): “Let us therefore establish first of all this principle, that we must bear the condition proper to humanity: it is impossible to remove social inequalities from the world.” He then continues: “Since the greatest variety exists by nature among men: not all possess the same ingenuity, the same diligence, the same health, or the same strength: and from these inevitable differences arise, of necessity, differences in social conditions” (RN #14).

The Thomism of Leo XIII and the editors he chose also emerges in the emphasis on the sociality of human beings and therefore on the ‘organicist’ view of society, which is the basis of the many paragraphs on associations and corporatism. In the Thomist system, the thesis that society is a body (St. Paul), and therefore all parts are interdependent, brought with it the necessity of hierarchy and the static nature of the places assigned to each (the finger is not the heart, and they cannot exchange functions). And so, RN decisively rejects class struggle and therefore the idea of conflict between bosses and proletarians (RN #15). From this harmonious view of social classes also arises Leo's invitation to revive the medieval Corporations of Arts and Crafts, which we already find in the encyclical Humanum Genus (1884). And then in RN we read: “To settle the labor question ... however, the guilds of arts and crafts hold the first place ... We are pleased to see associations of this kind forming everywhere, whether of workers alone or of workers and employers together” (#36). A thesis that seems bizarre today. As if, in the midst of the development of industrial capitalism and the working masses, it were possible to go back five centuries to an economy of a few commercial cities immersed in the feudal world; as if history and its ‘new things’ had nothing to teach the Church, which is part and daughter of that same history; as if those demands for equality were not also, at least in large part, the fruit of the Church's own gospel.

With his proposal for corporations, Leo XIII went beyond the thinking of the Italian drafters of RN and included some European thinkers, as highlighted in an essay by Alcide De Gasperi (signed with the pseudonym Mario Zanatta: I tempi e gli uomini che prepararono la RN, 1931). Above all, there were some Frenchmen, the Marquis La Tour du Pin-Chambly de la Charce (1834-1924), Count De Mun, and the entrepreneur Léon Harmel, promoters of Catholic corporatism, all of whom were aristocrats. In the revived guilds, class conflict would thus be overcome without upsetting the natural order of property and hierarchy: “There will always be that variety and disparity of condition without which human society cannot exist or even be conceived” (RN #27).

Concluding his discourse on proletarians and masters, Leo XIII writes: "In Christianity, there is a dogma on which the whole edifice of religion rests as its principal foundation: that the true life of man is that of the world to come. ... Whether you have an abundance of riches and other earthly goods or are deprived of them, it matters nothing to eternal happiness“ (RN #18). Therefore, ”it is understood that the true dignity and greatness of man is entirely moral, that is, rooted in virtue; equally attainable by the great and the small, the rich and the proletarians... Let us say more: it seems that God has a particular predilection for the unhappy, since Jesus Christ calls the poor blessed... Thus, the two classes, shaking hands, come to a friendly agreement" (#20).

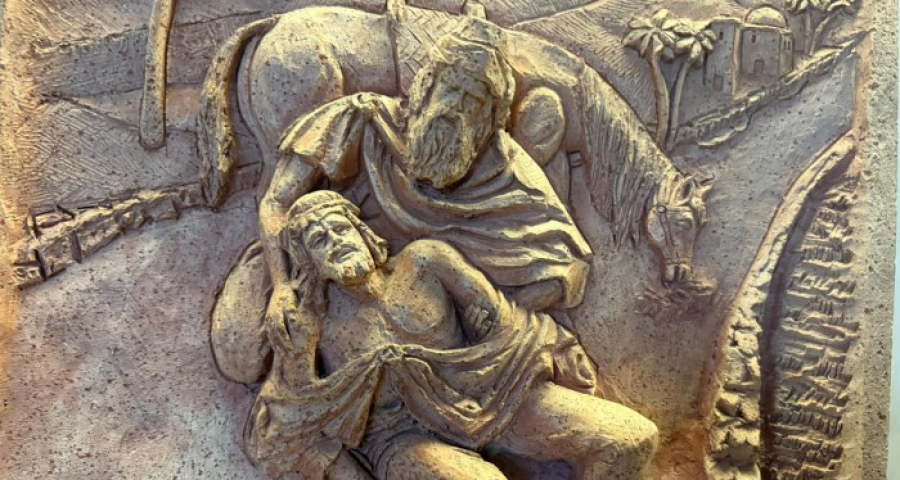

Reading these theses, we must pause, because we would find ourselves far from the spirit of the Gospel. Jesus healed the sick, raised the paralyzed from their beds, created a fraternal community that shared material goods, and did not console them by leaving them in their misery, waiting for paradise. He said ‘woe’ to the rich, gave us the parable of the rich man and Lazarus, and invited us to pass through the eye of the needle. His Kingdom was and is above all for this life, not for ‘the life to come’. What Leone wrote was an expression of the theology of the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic spirit of his time. After him came Vatican II, Don Mazzolari and Don Zeno, Francesca Cabrini and Pope Francis. Catholics have done little in the way of corporate ventures; those were done by the fascists. Instead, they gave life to trade unions, to many rural banks and cooperatives where they changed and questioned the property rights of capitalism, reduced the inequalities possible on this earth, and continue to do so. They went beyond the letter of Rerum Novarum, they listened to its spirit, which they also saw in the demands for equality of their time and of ours.

Today, we are going through similar times. Fear and nostalgia for the glorious days of the past can no longer be allowed to write the new Rerum Novarum.