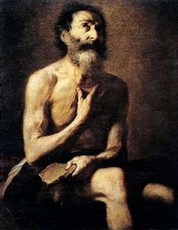

A Man Named Job/11 Let's find the sky in ourselves, faithful to the truth that is in us

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 24/05/2015

(Elie Wiesel, Biblical Characters Through the Midrash).

The history of religions and peoples is the unfolding of a real struggle between those who imprison God within ideologies and those who try to free him. The prophets belong to the category of the liberators of God who perform the essential function of criticism of all the powers in every age and overcome the invincible, tempting charm of using religions and ideologies to strengthen their dominant positions.

Job is one of these 'prophets', who - more than anyone else - forces us to go to the heart of the mechanism of power by criticizing and attacking directly the idea of God built by the ideologies of his time. Therefore he does not limit himself to the criticism of the powerful, the priests and kings, but just as and most of the great prophets of the Bible, he wants to dismantle the idea of God that is artificially supported by the whole edifice of power. His stubborn request to put the ideological God of his 'friends' to process is the precondition for liberating the possibility of another God.

When Job is eclipsed or silenced in a religious community, the answers in the name of God proliferate and questions to God disappear. And when we stop posing new and difficult questions to God, we prevent him from talking to our history and to grow inside it, we harness him in abstract categories that no longer understand the words and the cries of the victims. The prophets are essential because they call people to die and rise again to free themselves from idolatry, and because they force God to die and rise again to live up to the real human.

At the end of their discourse to Job, the three friends have not achieved anything. Job is increasingly convinced of his innocence, and so more and more determined to meet God in a fair trial where he hopes to be cleared by a different God that he cannot see yet but he can hear him. The theo-ideology of his interlocutors only reinforced the conviction of his own righteousness instead of reconciling him to their reasoning about God. Those dialogues, however, have had the great merit that through them we got to know Job and his radical religious and anthropological revolution. And so, that great pain and infinite misfortune that at first seemed to us as a high hedge of suffering that covered out the horizon of man and God have also gradually opened to a boundless space beyond and to new horizons of man and God.

As a link between the first and second part of the book, at this point we find a Hymn to Wisdom, perhaps an already existing poem inserted in the book by the author to break the narrative rhythm and let us take a breath. It is an interlude that's difficult to decipher but it is full of poetry, yet another gift of this great book. “Surely there is a mine for silver, and a place for gold that they refine"; man "searches out to the farthest limit the ore in gloom and deep darkness”, he creates shafts underground and to reach precious metals that "hang in the air”. The man of technology uses his intelligence to dominate the world: “He cuts out channels in the rocks, and his eye sees every precious thing. He dams up the streams so that they do not trickle, and the thing that is hidden he brings out to light." (28, 1-11) The ambivalence of technology is pointed out to us, however. Like any man of the antiquity, the author of the book of Job is amazed and humbled by the capacity that man has developed in dominating matter, things, the world. But inside technology he also sees the hidden but real risk of abuse: “As for the earth, out of it comes bread, but underneath it is turned up as by fire. ... Man puts his hand to the flinty rock and overturns mountains by the roots.” (28;5,9). Technology has its own intrinsic law that drives man to dig ever deeper tunnels, to topple the mountains in search of precious materials, thus starving the peasants who lived on the land, yesterday and today. Therefore, if we want to understand the biblical message about the relationship between man and nature, we must read the command of 'subduing the earth' contained in Genesis (1:28) along with this hymn in the Book of Job, where the value of the spirit of technology is recognized but it is also distinguished from the spirit of wisdom: “But where shall wisdom be found? And where is the place of understanding?” (28,12) Wisdom is not extracted inside mines, nor can it be bought in the market place in exchange for precious metals: “Gold and glass cannot equal it, nor can it be exchanged for jewels of fine gold. …The topaz of Ethiopia cannot equal it, nor can it be valued in pure gold.” (28,17-19).

To point out the innovative message of these words we must keep the culture of the time in mind that was all steeped in 'economic' theology. For the ancient Middle Eastern world it was certain that gold, silver, topaz and pearls did not buy wisdom; however, these were unmistakable signs of God's blessing, that same God from whom wisdom comes. And it was common to think that you will not become rich without wisdom. The spirit of the wealth and that of wisdom were considered the mirrors of one another. The fool does not become rich, and those born rich become poor if they lack wisdom. Just as the engineer and the scientist are not 'intelligent' if they lack wisdom.

This hymn, however, separates wealth (and technology) from wisdom, and in so doing it takes Job's side: in fact, he has reiterated to us that there is no relationship between wealth and justice, because there are rich and wretched among the righteous on this earth, and the same is true for the non-righteous. The gold and silver of a person does not say anything about his righteousness: Job was righteous as a rich man and continues to be so when he becomes poor and unfortunate, too. The goods pass and are changeable, justice and wisdom are forever, and so they are a much smarter investment. We could then read this interlude as a confirmation and approval of the 'theology' of Job and a critique of the economic and retributive theologies of his friends. This hymn to wisdom reminds us of the ancient and important truth that wisdom is a gift and gratuitousness: charis, not a commodity to be purchased with either gold or through soothsayers or magicians. Here, too, YHWH-Elohim is distinguished from the idols that only give their 'wisdom' to their flatterers if they pay the price in terms of sacrifice and submission. The God of the Bible is not an idol because he does not sell wisdom, but gives it freely - every retributive religion is, in essence, an idolatrous and commercial religion. Words that could have been uttered by Job, too.

But - and here it is the mystery and the interest of this chapter - the author tells us something else that complicates the discourse, and forces us to dig deeper. He tells us that wisdom is unknowable and unreachable by man: “God (only) understands the way to it, and he knows its place.” (28,23).

And here there is a definite distance created from Job. Not all of the book of Job is at level with Job. We have to select and save Job's words from the many other words of his book, including those of Elohim that soon we will also hear.

Job denies the law that connects justice to wealth, but believes that there is, there must be a logic of wisdom. The God whom he calls and waits for is not an accountant who assigns assets to men according to their merits, because that would make him a trivial god just like all the idols. But he does not accept the idea that there is no link between justice and wisdom: the righteous one is wise, even if he is poor and unfortunate. And the proof of this is the history and the life of all those for whom wisdom does not coincide with the intelligence of technology, but where there exists a relationship between righteousness and wisdom, and it is a real one. We know people who are wise and ignorant, wise and poor, wise and not very intelligent. The homo faber and the homo oeconomicus may be foolish, and often they are, too. The righteous man is not foolish, because God - if he is not an idol - must give wisdom to those who follow justice, even when its following (as in Job's case) means denying the justice of Elohim.

A false, unjust and evil person is never wise: this law is as real as that which moves the sun and other stars. An unjust man can hope for all other goods, but not in that of wisdom. Job knows this law because he sees it in the world, but mainly because he carries it inscribed in his conscience. And we also know it and recognize it outside and inside us (that's why there is hope that we can always convert, even with the last breath of life). So the mine of wisdom exists: it is inside us, and to discover it, the only thing necessary is to remain faithful to the truth that is in us. This is the main message of Job.

This hymn to wisdom then contains a half-truth. It reminds us that wisdom is a gift, but it does not tell us that we receive this gift right upon coming into the world, and it dwells in us. It is there where we can dig to reach him, and once reached we find that it is the best part of us. That's where we can meet, discover, listen to and follow wisdom. That's where we can recognize the voice of Elohim, a voice that we could not recognize if it weren't already within us, perhaps covered or wounded. If Adam was kneaded in the image of Elohim, divine wisdom is also human wisdom. The sky within us is no different from the sky above us, and the inner sky darkens, the one above us goes out or fills with idols.

The song of Job is a great hymn to the truth of the living human, which is truer than all of his nights. If God is true then man is also true, and his clear conscience is not a self-deception. If God is wisdom then man is also wisdom. If we separate these two wisdom-truths - we have done so many times, and we still do - religions become useless, humanisms are lost, and Job ends his song.

Download pdf