A Man Named Job/12 - Nostalgia about the future where God's sky and man's horizon meet

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 31/05/2015

Turning to Nairobi (where I'm writing this), the cry of Job here is deafening; and our non-response masked by ideologies resonates everywhere. If you hope to remain righteous, the only way you can walk in the unruly "peripheries of capitalism" is to do it in Job's company. You should recognize him in the streets, take a closer look at his wounds, and at least try to be quiet to really hear his cry.

Job's friends have stopped talking. He is left on his dunghill, wounded in body and sunk in the darkness of his heart that only Elohim may lighten up by pronouncing words that are different from those declared by his interlocutors, the adulators of God and the enemies of the victims and the unfortunate . Elohim, however, does not come. His absence is becoming the most cumbersome presence in the centre of the drama.

Job invoked him, he sued him, summoned him to court as a judge to protect him from God himself, he even delivered a first oath of innocence; but Elohim does not enter the courtroom, he is not talking or responding to him. And in this waiting for a different God that is slow to come, nostalgia hits Job on the dunghill: "Oh, that I were as in the months of old...as in the days when...the friendship of God was upon my tent, when the Almighty was yet with me, when my children were all around me” (29,2-5). It is a nostalgia that sharpens his pain. It is joyful to remembers the spring during winter when it is believed or hoped that the spring of yesterday is going to come back tomorrow. But when winter does not blossom in a new spring, when the night does not generate a new dawn because it is the last night, the memory of the times of light and buds only increases the suffering in the cold of that last winter. Memories of youth are painful in old age if we do not have at least one child with us in whom we may feel our future youth revive, all different, being all and only gratuitousness. The only nostalgia that has a saving power is the nostalgia of the future.

But in that last memory of the blessed days there are many other things, too. First of all, Job finds a further, final proof of his innocence and righteousness: “I was eyes to the blind and feet to the lame. I was a father to the needy”. And in the same poetic tone he keeps offering to us, he adds: “I have made a covenant with my eyes; how then could I gaze at a virgin?” (29, 15-16; 31,1). And as a thesis to add to that of his innocence, we find his accusation to God again, which is ever clearer, louder and more and more outrageous and wonderful: “God has cast me into the mire, and I have become like dust and ashes. I cry to you for help and you do not answer me; I stand, and you only look at me.” (30,19-20). The biblical God is a God who is close to the poor and responds to the innocent who calls on him; he is close to the victims, he runs to the aid of those who cry out. The God whom Job is experiencing is not like that: Job cries out and God does not come.

If the Bible wanted to show us a God who is not responding to Job, then it should be possible to find truth in a God that does not respond when he should. If we take a good look at the world we discover that God still does not answer Job who is crying out. This mute God is the one that the poor of the earth know. Then, perhaps, if we truly hope to find the spirit of God in the world, and not to be caught by some idol in and outside of the religions, we should find him inside the unanswered cries, we should look for him where he isn't.

The last words of Job then contain an immense 'oath of innocence' ('if I have committed this crime, let this evil hit me'...). Job has already pronounced it earlier (27,1-7), but now he does it in a more solemn, final, extreme way. It is a last oath that contains a precious pearl, one of the greatest and most revolutionary messages of the entire book and of all books. In his last words we max discover what innocence consists in really for Job: “If my heart has been enticed toward a woman, and I have lain in wait at my neighbour’s door, then let my wife grind for another and let others bow down on her ... If I have withheld anything that the poor desired, or have caused the eyes of the widow to fail, or have eaten my morsel alone, and the fatherless has not eaten of it ... then let my shoulder blade fall from my shoulder, and let my arm be broken from its socket. ... If I have made gold my trust or called fine gold my confidence ... if I have looked at the sun when it shone, or the moon moving in splendour, and my heart has been secretly enticed, and my mouth has kissed my hand ...” (31,9-27). Maltreating the poor and not helping them, adultery and the many forms of idolatry (wealth and the stars): these are the most serious crimes for Job and for all.

But at a certain point Job adds something that leaves us perplexed, amazed and dirsturbed at first. It seems that Job actually admits to his guilt at the end of his argument “I have not concealed my transgressions as others do by hiding my iniquity in my heart” (31,33). He gives it up right in the last act of his defence, a few steps from the finish, and following the advice of his friends he admits to being guilty, he denies his innocence that was the only good he had saved in this total meltdown. Is this the meaning of these words? No. Job here is telling us something different and very important: his last words, as a testament.

Recognizing his guilt Job concludes his speech by expanding the territory of human innocence to cover sin, too. The righteous man is not the one who does not sin and does not commit crimes, because sin is part of the human condition. Job has always denied the economic theology of his friends who associated his unfortunate condition to his sin. Now we understand fully that Job's justice and innocence do not consist in the absence of sins of moral lapses. Even Job sinned. You can commit sins and crimes and still remain righteous if you do not depart from the truth about yourself and the truth about life. The only great sin against the God of Job is telling lies, the sin of those who know they are wrong and still 'hide their iniquity in their heart' because admitting and recognizing it publicly would demonstrate their intention of conversion, and so they would remain righteous. There are people who are unjust and not innocent who receive public praise and civil honours and the prisons are full of righteous people like Job. God, if he is not an idol, is not free not to forgive the sins of the righteous. So with his last words Job is telling us something decisive for every experience of faith: even the sinner can remain innocent. And if even the sinner stays in the territory of innocence, then you can always raise after every fall: innocent people can return. Job knows, because he believes and hopes only in this God.

It is with this sincere, genuine and honest innocence that Job ends the telling of his story. He has done his job, he finished his mission. He fought a good fight. He has kept the faith in man, in Elohim, in his own dignity and honour, in the innocence of man, of every man. And he did it for us, he continues to do it for us to include sinners who continue to be righteous in the realm of the innocent.

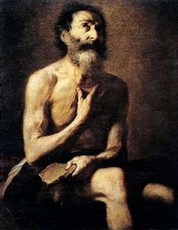

Now he can only wait for God to also play his part, waiting for his appearance in the courtroom of the earth. It is there that he is waiting for him: “Here is my signature! Let the Almighty answer me! ...like a prince I would approach him” (35,35-37). Job has stood his test with the dignity of a free and true man. He feels like a king, "a prince", and can expect God with his head lifted up.

Job is in the time of Advent, he is still waiting for God; but now he knows that if he comes he will be different from the God of his youth. That first Elohim was blown away by the strong wind that wiped out all that he had. But he never ceased waiting, he continues to have a nostalgia for God, a nostalgia for the future.

In the trials of life, even those that are great and tremendous, the important thing, the only really important thing is to get to the end of the night, not to stop waiting for another God, and to reach this decisive meeting with our head high. Not all waits for God take place with head-high, because to hold your head high and be able to look in the eyes when Elohim he comes you also have to go through trials like Job, and not to be content with a lesser God and a worse man in order to be saved.

Job gets to the end of his defence like a prince and having continued to expand the horizon of the good human until it coincides, on the horizon line, with the good sky of his God.

Download pdf