A Man Named Job/2 - Persisting without cursing, discovering the "freedom of the manure"

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 22/03/2015

Sergio Quinzio, Christianity of the Beginning and the End

Richness, all human wealth, all our wealth, is first of all gift. We come into the world naked, and begin our journey on earth thanks to the generosity of two hands that receive us when we reach the world. We receive the gift of the inheritance of thousands of years of civilization, brilliance and beauty that are donated to us without any merit on our part. We are born inside institutions that had been there before we arrived, ones that take care of us, protect and love us. Our merit is always subsidiary to the gift, and it is much smaller. However, we keep creating more and more injustice in the name of meritocracy, and living as if wealth and consumption could cancel the nudity we come from and that always awaits us faithfully at the crossings of all roads of life.

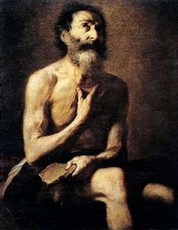

Satan ("the opposer") loses his first challenge because despite his strong wind that swept away all Job's possessions, he did not curse God: “In all this Job did not sin or charge God with wrong” (1,22). But Satan is not yet convinced of the gratuitousness of Job's faith, and so he asks God's permission to test him for the last thing he has left: his own body. And so, in a new meeting of the heavenly court, he takes the floor and asks for more: “Skin for skin! All that a man has he will give for his life. But stretch out your hand and touch his bone and his flesh, and he will curse you to your face” (2,4-5). God answers him: “»Behold, he is in your hand; only spare his life.« So Satan (...) struck Job with loathsome sores from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head. And he took a piece of broken pottery with which to scrape himself while he sat in the ashes” (2,7-8).

The misfortune of Job reaches the limits of the possible. His bare life is all what is left to him. But just like Job, only when we are in a total havoc do we discover unknown resources that make us able to endure sufferings that we thought were unbearable before experiencing them. It is a strength that may surprise us even when we discover that we are able to die, though all our life we have been thinking the opposite.

With the second chapter of the Book of Job, the horizon of the good human being, friend of God, continues to widen, and no human condition is symbolically excluded. Job sitting among the ashes, in the middle of the villagers' garbage, touching the lowest point of the human condition, the most distant existential peripheries, waste, the "losers" , all the dross of history. The dumps were located outside the walls - and since Job's skin disease (perhaps something similar to leprosy) marks him as unclean, and he must be cast out, together with those who have been "excommunicated". For the man of the Middle East nothing like the infectious disease of the skin was a sure sign of the curse that God reserves only for sinners. In the "economic" religions of the past (and also in those of today, in our big enterprises and banks), misfortune and impurities are considered as the effects of a life as a sinner. It is this equivalence that Job does not want to accept - either for himself or for us. From being a rich and powerful man, Job suddenly finds himself unfortunate, impure, and therefore untouchable, excluded from all the social castes. This is still the sad fate of entrepreneurs, managers, workers, politicians, priests that, having fallen into disrepair, find themselves not only impoverished, but sitting on a pile of rubble which includes family, friends and health, too. And they immediately end up among the unclean, cast out from the village, away and marginalized by the clubs, associations, groups, confined in social and relational landfills, shunned by all and never touched for fear of being infected by their ruin.

Job, however, sitting on ashes and manure, with the piece of broken pottery in his hand, did not curse God. He remained a righteous man. There is no greater gratuity than his who hopes and wishes that God exists and is righteous even when he does not see either the signs of his presence or those of his righteousness in his personal life. Job continues to seek truth and justice. It is a desperate search that has an immense ethical and spiritual value if we think that in the Old Testament (including the Book of Job) the idea of the existence of life after death is very vague, almost non-existent. The place where YHWH lives and where you can meet his blessing is this earth, not another location. The struggle of Job therefore embraces every human being who wants to learn living content with no simple answers, not even those really simple ones provided by atheism. Job, in every era, continues to fight for them.

If life works and flourishes there inevitably comes a stage of the pile of ashes. It is the appointment with unchosen poverty. As long as it is our choice to be poor, we are perhaps in the realm of the virtues, but we are still not in that of Job. Poverty by choice has and still generates many good lives, but it is not the poverty of Job: Job is a rich and happy man that becomes poor without choosing it, and this is why his condition embraces the poverty of everyone, especially those who find themselves in it without having chosen it. It is a radical and universal poverty, because while those who chose poverty as a way of living have always been only a few (even fewer are those who manage to free themselves from the richness of having freely chosen poverty), many, and potentially all of us can go through the experience of becoming poor without it either asking for or choosing it. And there we meet Job, who is waiting for us and fighting with and for us. Like when, after spending a lifetime to build a spiritual wealth, one day, almost always unexpectedly, you find yourself naked on a pile of manure, deprived of all the "goods" that you had accumulated. I have had the gift of knowing some great people who found the radical freedom of the manure only as they were preparing to die, when they were free from all the riches, especially spiritual ones, starting on a new flight finally freely, even if it lasted only a few years, months, sometimes days or hours. This radical and unchosen poverty makes us become those "little ones" who manage to enter into another realm, because they are able to see and desire it first.

Job sitting in the ashes is not totally alone. His wife and then some friends go to see him. The wife makes her quick, unhappy and only appearance, while friends will star in all the drama of Job. “Then his wife said to him, »Do you still hold fast your integrity? Curse God and die«” (2,9). These are mysterious words and they lend themselves to many possible explanations, but they are not rare in the life of the righteous who have fallen into misfortune, when at the height of a great test the people closest to them become the most distant ones, because in addition to not understanding what they are going through, these wives, fathers and husbands end up giving advice that is the not wise or true at all, even if they do so out of love or pity. His wife comes to Job with an invitation to surrender, to commit suicide and to die. But Job does not listen to her: “You speak as one of the foolish women would speak. Shall we receive good from God, and shall we not receive evil?" (2,10). Job did not choose death, and although (as we shall see) he will feel the temptation of wanting to die, he will live, fight and search for a sense: "In all this Job did not sin with his lips." (2,10)

Job did not curse God. However, he cursed himself and his own life, a self-curse worth a poem and a humanity that will leave us breathless, and that after thousands of years still has the power to move us, convert us and push us to seek at least one Job around us, and accompany him through these amazing pages. This is how we can discover a new prayer, perhaps the most beautiful one of all. Every time we re-read the Book of Job, Ecclesiastes or Mark, we can lend words to the many people muted by pain and life who cannot, do not manage or do not want to cry out their immense and true sorrows. You can start or restart to pray - throughout life, one forgets to pray and then relearns it many times - by borrowing the extreme words of Job, until they become ours, and of those who do not have words anymore.

Job's poem is the revelation of the immense depth of the moral sturdiness of man, who is able to continue to bless God in the midst of radical and undeserved misfortune, without any reciprocity available to him. Throughout all his drama, Job will try to make sense of this lack of reciprocity by God, and so does every reader who reads the Book of Job in a Bible that is based on the "contractual" reciprocity of the Covenant and the Law (Torah). What will be the reciprocity by God?

The bet between Satan and Elohim is not won by either of them: the real winner is Job, who "forces" God himself to break free from the retributive, economic and contractual type of logic. Asking him to become something in his eyes of a man that is: Other.

Thanks to Job, a man who remained faithful even without reciprocity, God has to continue to love us even when we stop doing so. He can, and must be present even in a world that does not want him, does not see him and does not desire him anymore.

Download pdf