Greater Than Guilt/25 - Every fratricide story is, unfortunately, real

by Luigino Bruni

published in Avvenire on 08/07/2018

“Ulysses, noble son of Laertes, stop this warful strife, or Jove will be angry with you.” Thus spoke Minerva, and Ulysses obeyed her gladly.

“Ulysses, noble son of Laertes, stop this warful strife, or Jove will be angry with you.” Thus spoke Minerva, and Ulysses obeyed her gladly.

Homer, Odyssey; Conclusion (English translation by Samuel Butler)

When we go through deep and complex crises, meeting with someone who shows us another perspective can be a decisive event. Someone who makes us climb a hill to look up from above at our besieged city, and from there discover escape routes that we could not see when we were still immersed in fighting. In the Bible those who offer these different perspectives are mainly prophets and women. There is, in fact, an analogy between prophecy and female genius. Both are concrete, they activate processes, they speak with words and the body and by an invincible instinct they always choose life and believe in it and celebrate it to the last breath. Prophets and mothers host and generate a living word that they do not control; they offer their body to it so that the word-son becomes flesh, without becoming its masters.

Blood and violence continue to flow copiously in David's family history. The actors of violence are males who demonstrate a great malevolence of the head, joining that of the belly. Among all the men who are writing the blood-soaked first pages of the history of the monarchy in Israel, every now and then there are some women that humanize the stories and show the other face of YHWH with their brief appearances. Women come on stage to tell us new words about man and God when males have consumed and squandered their last resources of humanity, and have become beggars of words of life. In these tremendous pages on the fratricidal struggles of the sons of David, it is a woman again to illuminate the dark horizon of men with a very bright light.

David, who learned of the rape of his daughter Tamar, also shows himself to be ambivalent here: “When King David heard of all these things, he was very angry. But he would not punish his son Amnon, because he loved him, since he was his firstborn” (2 Samuel 13:21; the second sentence is added from the Septuagint and the Dead Sea Scroll - the tr.). History is full of crimes, especially against the poor, women and children, that are covered by "fathers" so they don’t have to "punish" their children. Absalom, however, has an opposite reaction. He begins to cultivate the devastating feeling of revenge. And so, two years later, during a feast of the shearing of his flocks, Absalom obtains David's permission for his brother Amnon to go to him. Then he tells his servants: “Mark when Amnon's heart is merry with wine, and when I say to you, ‘Strike Amnon,’ then kill him. Do not fear” (13:28). Once again: a brother who invites another brother to "go to the fields": “So the servants of Absalom did to Amnon as Absalom had commanded” (13:29). Amnon, unlike Abel, was guilty, but no brother deserves to die. After the fratricide, Absalom, like Cain, escapes and starts wandering, having become a murderer and therefore being at risk of death. But into the night of this fratricide another woman arrives, this time without a name: the woman from Tekoa.

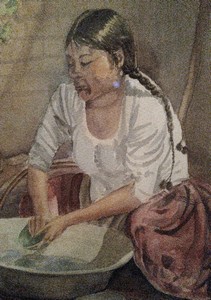

Joab, David's cunning and ambiguous general whom we already know, wants to rehabilitate Absalom and make him return from exile: (he) “sent to Tekoa and brought from there a wise woman” (14:2). To the Biblical reader the name of Tekoa immediately says something important: it is the village of the prophet Amos. We are therefore in a prophetic environment. The woman is called "wise", a rare adjective that means a lot in the Bible. Here too, as in Abigail's story, the woman presents herself as a narrator, as a weaver of stories, an artisan of the word at the service of life. Women have a very special relationship with storytelling. Maybe because when they were very young they taught us to transform the first sounds and noises into words, because they nourished their children with milk, food and stories, or maybe because for thousands of years while the males were hunting or fighting, they, under the tents, exchanged above all words - women know how to speak differently and better than men. Above all, they can look for, create and invent words that are not yet there, but that absolutely must be there for life to continue. The wise woman of Tekoa did the same.

Joab instructs the woman and sends her to the king: “Pretend to be a mourner and put on mourning garments. Do not anoint yourself with oil, but behave like a woman who has been mourning many days for the dead. Go to the king and speak thus to him” (14:2-3). She goes to David, saying, “Save me, O king.” And the king said to her, “What is your trouble?” (14:4). She tells him the story invented by and agreed with Joab: “Alas, I am a widow; my husband is dead. And your servant had two sons, and they quarrelled with one another in the field. There was no one to separate them, and one struck the other and killed him. And now the whole clan has risen against your servant, and they say, ‘Give up the man who struck his brother, that we may put him to death for the life of his brother whom he killed.’ And so they would destroy the heir also. Thus they would quench my coal that is left and leave to my husband neither name nor remnant on the face of the earth” (14:5-7). This narration shows an extraordinary emotional and relational intelligence.

The woman invites David to see the only vital perspective available, the one capable of a future. She invites him to move away from the destructive logic of past faults and recriminations, and to see the objective, present and future costs and benefits of actions and reactions. That son is dead, and his life doesn't return anymore. To allow that the logic of revenge, all played on the past, should also kill the second child, does not mean repairing the damage but doubling it, turning off the only "coal" that can still light life. A woman here is explaining to us one of the greatest juridical and human truths in history: forgiveness and reconciliation are not only the most human and religious choice we can make in the face of a crime, but they are also the most intelligent choice because they are the only ones capable of not worsening the damage. It is thanks to a discourse similar to the logic of this wise woman that one day we abolished the law of retaliation and the vision of punishment as collective revenge. And we have become more humane and more intelligent.

As with Nathan's parable, here too David perfectly carries out the empathic exercise that the woman proposes to him (David’s greatness shows in how he can listen to men and women): “He said, »As the Lord lives, not one hair of your son shall fall to the ground«” (14:11). Guided by the narrative of the wise woman, David now understands that the good of that family lies only in violating the law of retaliation and breaking the spiral of revenge. Then the woman continues, leaving the invented story and arriving directly at the real purpose of her visit: “Why then have you planned such a thing against the people of God? For in giving this decision the king convicts himself, inasmuch as the king does not bring his banished one home again” (14:13). Nathan (ch. 12) had concluded his parable with the tremendous phrase: “You are the man”. The wise woman now tells him something very similar: "You convict yourself", because with his own son David is not doing the justice he swore to do with the woman's son.

Then David senses that "the hand of Ioab” is in this whole affair. The woman does not deny it: “It was your servant Joab who commanded me... In order to change the course of things your servant Joab did this” (14:19-20). The king does not seem disturbed by Joab's hand, and by the different perspective he gave him: “Then the king said to Joab, “Behold now, I grant this; go, bring back the young man Absalom” (14:21). Joab's goal is achieved. And the wise woman disappears after this beautiful page. The text and Joab choose a woman to try to put an end to repeated violence. The Bible is aware of the specific virtues of women, it knows that the female gaze can be decisive in conflict resolution. She sees and tells about a world of males who wage wars, kill each other and kill and rape women. She knows that the world she describes has not been able to recognize and respect the talent of women, to call them by name and give them equal rights and dignity - this tale doesn’t reveal the name of the wise woman of Tekoa, either. But the Bible also preserves its own knowledge of women, of their mystery and dignity, of their virtues and special talents. As if to say, “If we had listened more to the wisdom of women we would have sinned and suffered less, we would have been more humane, we would have had less violence and more shalom. But, unfortunately, we haven’t managed to do so”. History, conflicts and wars are seen differently through the eyes of women and mothers. That has always been the case. The Bible is immense also because in a world dominated by men it has also left us some words of women, masterpieces of beauty, of pietas, of humanity, of other magnificats.

The story told by the wise woman is similar to the parable of Nathan's little lamb. In his case it is the status of prophet that legitimises Nathan to "invent" a story and give that parable a force of truth capable of moving and converting David. The woman performs a real staging (she puts on mourning clothes), a theatrical piece, a fiction that acquires the same truth as real life. Artists create stories every day that we know are very true even if they are "invented", because Edmond Dantès and Gregor Samsa are as true as our friends are. The wise woman comes to the king, tells him an untrue story of a killed son, the king realizes that the woman came to him out of Joab’s design. But that untrue story and that staging are not condemned by either the king or the text. Maybe because, simply, that story was all true, it was an embodied, living parable. The wise woman was telling David about one of the many fratricides that mothers on earth have to witness. It was the collective mastery of mothers' pain that made that invented story a true and prophetic one. The story of the wise woman was not the staging of Joab's plot. It was much more. Only a woman could tell such an invented story without telling a lie. Joab had written the part, but the woman performed it with the same freedom and creativity with which a jazz song is performed. Because if Eve, the first woman, was the mother of a fratricidal son, then every time a woman tells a story of fratricide she always tells a true story. But she never tells a story of death only.

download article in pdf