Every religious experience has a consumer dimension. People do not go to church, and did not go in past centuries, solely to fulfill a moral obligation, out of fear of hell, or to avoid discrimination by their fellow citizens.

by Luigino Bruni

published in Messaggero di Sant'Antonio on 02/05/2025

The language of economics can sometimes help us understand phenomena that have little to do with economics. Religion, and faith in general, are among those realities that reveal something about themselves when expressed in the language of economics. Every religious experience has a consumer dimension. People do not go to church, and did not go in past centuries, solely to fulfill a moral obligation, out of fear of hell, or to avoid discrimination from their fellow villagers. People also went to church because they enjoyed immersing themselves for an hour in a positive atmosphere, feasting their eyes on paintings of saints, the Virgin Mary, and Jesus, touching the statues of St. Anthony and St. Rita, and breathing in the smell of incense. And then we loved the processions, the singing, the canopies, the gunshots, the Via Crucis when we all cried and recognized ourselves in Jesus, crucified on our own crosses, and rose again with him. In a short, sad, and poor life, Masses and services were our luxury goods: we entered those beautiful places and felt, for a while, almost like the rich and the lords. We too consumed emotions, relational goods, comfort goods, music, art, songs, and the Eucharist.

Even today, we do not understand religious practice without its consumer dimension. If we look at the places and communities that still attract young people, we certainly find many consumer goods that satisfy people's needs. Experiences of strong emotions, singing together, witnessing healings, entering into a sort of ecstatic trance with songs sung and repeated for a long time, all together. And we also find the consumption of relational goods: being together with others, feeling the same things, saying the same prayers, performing the same acts of service. Certainly, we are together doing something “for” others and “for” God, but also, and perhaps above all, to do something “with” others. There is no religious experience without this special kind of consumption, and if a community that was once flourishing and is now in crisis wants to attempt a new spring, it must ask itself what it can offer people in response to their new needs.

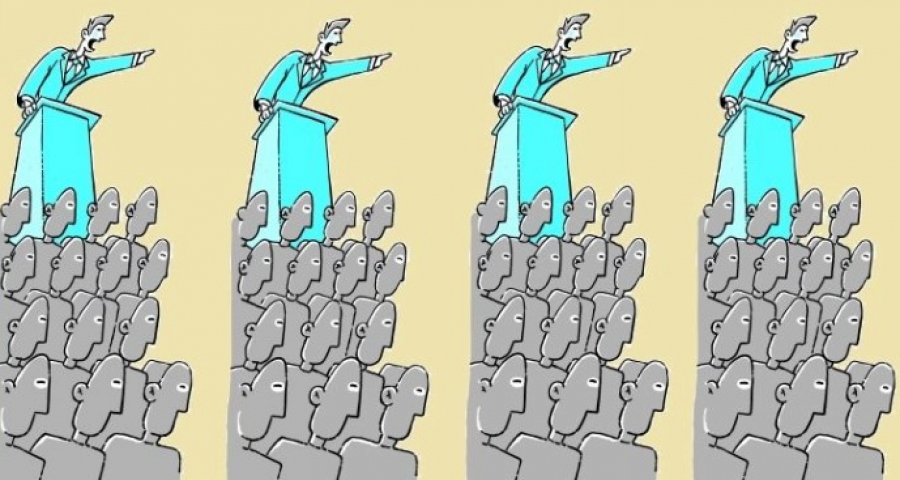

But, and here's the point, if common consumption and the collective comfort zone exceed a critical threshold, that consumption turns from a blessing into a curse. The day we attend Mass, meetings, and services solely or primarily to consume emotions, religion becomes a mere comfort and a form of spiritual consumerism. It is an experience that no longer asks anything important of us, but merely entertains us with emotional flows very similar to watching TV or a show. The wisdom of community leaders lies almost entirely in understanding when necessary consumption is crossing that invisible threshold, and stopping while there is still time. How? By leaving home, leaving churches and comfortable places to return poor and free along the road. Like Francis, like Christ.